San Diegans Can Drink Their Tap Water. Many Pay More at the Vending Machine Anyway.

The story was originally published in Voice of San Diego with support from our 2024 California Health Equity Fellowship.

Andrew Whiting fills water jugs at Aqua Bar in Escondido on Oct. 25, 2024.

Photo by Kristian Carreon for Voice of San Diego

On a May afternoon, customers fill empty five-gallon jugs at vending machines beside the front door of the Aqua Bar water store in Escondido. Inside, the store’s owner chats with regulars turning the faucets at two large metal sinks. Customers come and go, wheeling carts full of newly-filled containers out to the trunks or flat-beds of waiting cars.

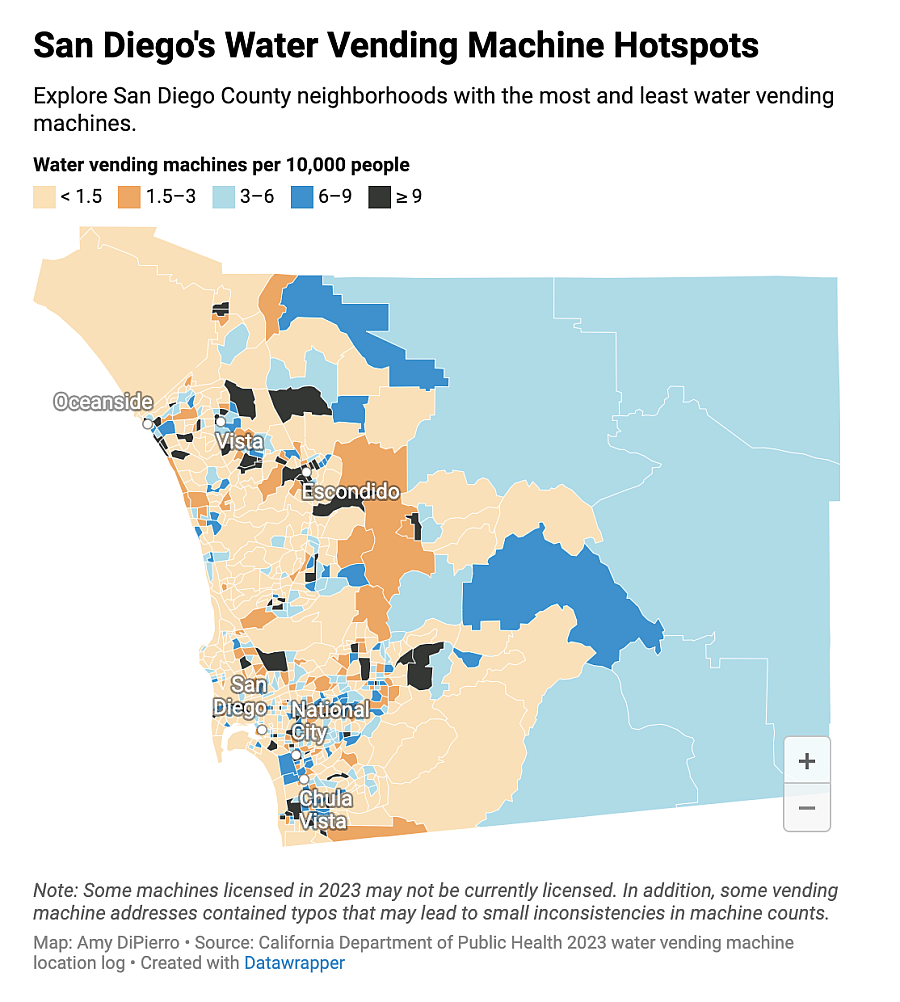

Aqua Bar is roughly in the middle of a neighborhood that could be the water vending machine capital of San Diego County.

The ratio of water vending machines to people is about eight times the county average in this corner of Escondido.

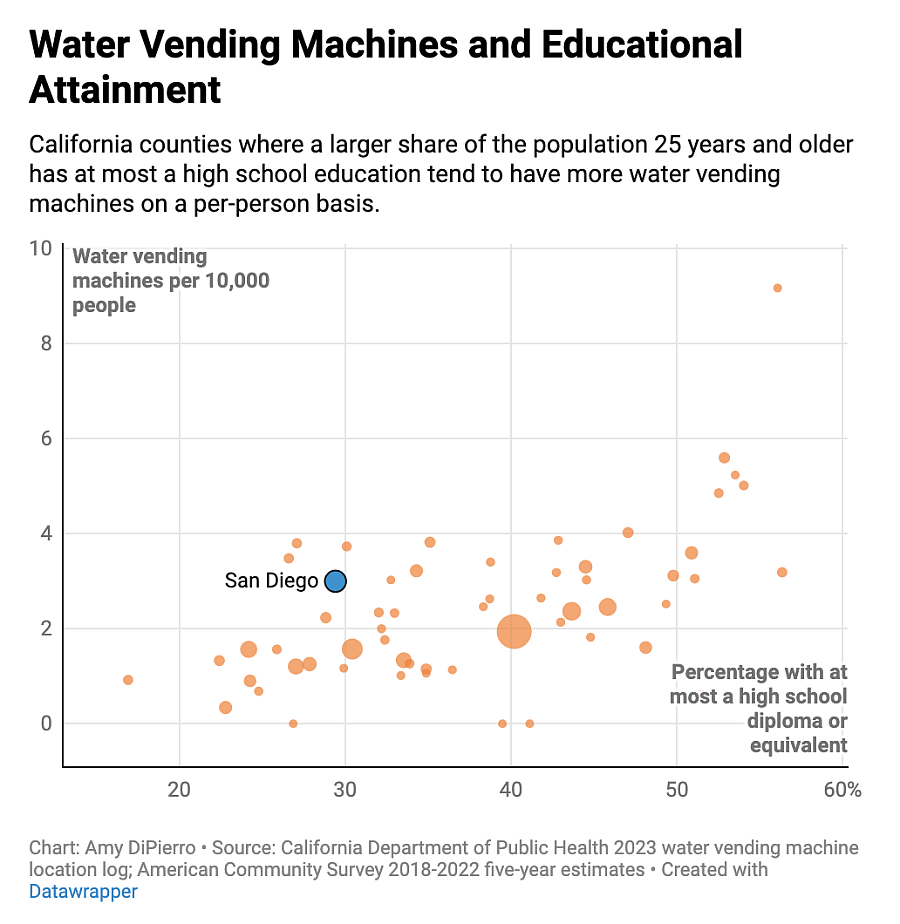

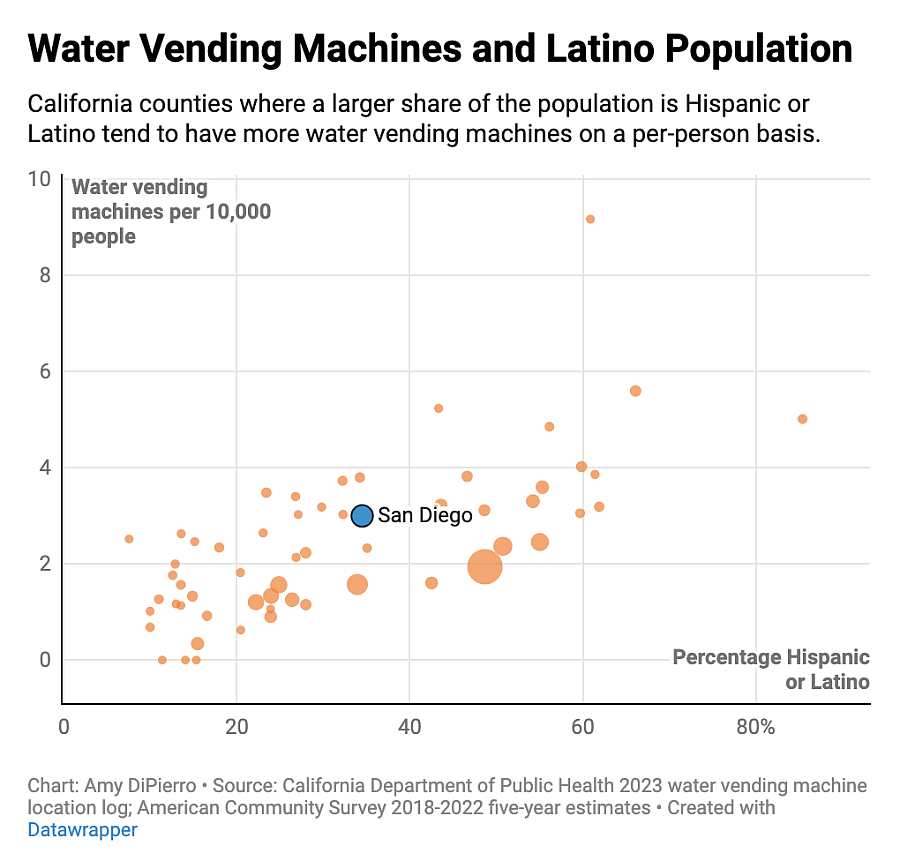

San Diego County itself boasts roughly three water vending machines per 10,000 people — more than nearby Riverside, Orange and Los Angeles counties, according to Voice of San Diego’s analysis of 2023 licensing records from the California Department of Public Health.

Demand for vended water does not appear to be related to municipal water quality. The data show that water vending machines are most concentrated in the corners of San Diego County with lower incomes and college attainment and higher percentages of rental units, non-citizens and Latinos – neighborhoods not unlike the one where Aqua Bar is located.

Social science researchers have seen the same patterns in other places and said consumers learn to distrust their tap water after seeing other government services fail. Vending machine customers told me they also want to avoid more expensive bottled water and worry that odd tasting tap water is bad for their health.

A preference for vended water in cities like San Diego – where tap water is highly regulated and generally meets public health standards – might seem a little surprising. Vending machine customers pay about 30 to 50 cents per gallon, a notable markup over the penny or two a gallon a typical tap water user pays at home. (Another thing to note: We've reported before how the industry is regulated relatively lightly. And that's still the case.)

“These are folks who can ill afford to spend that kind of money on what is really not a necessary thing,” said Manny Teodoro, a researcher who studied the water vending machine industry in a 2022 book, “The Profits of Distrust.” “Money spent on (vended) water is money that's not spent on healthier food, on perhaps needed medicine and healthcare.”

Aqua Bar customer Sergio Ramirez fills about two five-gallon jugs each week. A contractor for local water utilities, he prefers the way filtered water tastes. But he noted that tap water utilities don’t control the pipes that connect a municipal water system’s infrastructure to the taps in a home or apartment.

“After the water meter – that’s another thing,” he said. “You never know what a home builder or owner is using.”

Concerns about the pipes inside their own homes are a common refrain among people using water vending machines. A customer using a Watermill Express kiosk in National City said tap water “tastes like the pipes aren’t clean.” At a nearby Primo Water vending machine in San Diego, a woman said the old plumbing in her apartment makes her leery of drinking tap.

University of California, Los Angeles researcher Gregory Pierce said those worries may reflect water quality issues that don’t show up in municipal water data because they arise in the premise plumbing, the pipes that are the responsibility of landlords and homeowners.

“People may be distrusting their tap water and still buying much more expensive water, even though they have less income, because they may be experiencing things that you can't observe in the official water quality data,” Pierce said.

There are roughly 900 water vending machines around San Diego County — outside of liquor stores and supermarkets, at kiosks shaped like watermills and blue coolers the height of a man. To understand where there tends to be the most demand for them, Voice of San Diego ranked Census tracts by a range of socioeconomic and demographic factors, then compared the number of vending machines per person in the bottom and top fifth of each category.

Income and rental units were two of the biggest divides. Census tracts with the highest shares of people living beneath the poverty level had more than triple the number of water vending machines per person as those with the lowest poverty. Similarly, neighborhoods with the largest percentage of rental units had three times as many water vending machines per person as those with the fewest rentals.

Vended water could appeal to renters and households with lower incomes for a few reasons.

Pierce and colleague Itzel Vasquez-Rodriguez observe that controlling how tap water looks, smells and tastes – what the water industry calls aesthetics – is particularly hard for renters, who may be reluctant to raise concerns about water quality with landlords who could hike their rent to cover the cost of plumbing upgrades.

Low-income consumers, meanwhile, may see vended water as a bargain. Several customers interviewed at water stores and vending machines said vended water is an economical alternative to getting water delivered or buying bottled water at the grocery store, not an expensive substitute for tap water.

“Generally, people don't realize how much they're spending on small things repeatedly, as opposed to big things like utility bills,” Pierce said.

Another thing that separates neighborhoods with more water vending machines per person from those with fewer: education levels. The analysis found more than four times as many vending machines per person in Census tracts with the largest percentage of adults with no college education as in tracts where that demographic was smallest.

More highly-educated people tend to trust water more simply because they have more information about it, Pierce said. It could also be that education is correlated with income.

The next largest gap was across ethnicity. Strongly Latino tracts had almost four times as many vending machines per person as tracts with the smallest share of Latino residents.

Negative experiences with tap water agencies in other countries could be a factor. The analysis found almost three times as many water vending machines per person in tracts with the highest percentage of non-citizen residents as in tracts with the least non-citizens.

“It just carries on from generation to generation that you don't drink the [tap] water,” said Carlos Quintero, the general manager of the Sweetwater Authority, who said he himself grew up purchasing five-gallon containers of water from a local store in Tijuana. “So then people move here to the U.S., and there's still that perception that the water is not safe to drink.”

But distrust linked to tap water failures outside the United States isn’t the whole story, Teodoro and his co-authors, Samantha Zuhlke and David Switzer, argue. They say experiences of discrimination in the United States can also sour consumers on drinking tap water in the long term.

The researchers found more water vending machines in neighborhoods that were redlined in the 1930s. They found higher per capita bottled water sales in North Carolina counties that lacked enhanced federal oversight under the 1965 Voting Rights Act, which banned discriminatory voting practices. And in Phoenix and Houston – where Teodoro and colleagues argue that the same twentieth century reformers behind city water projects also worked to curb Hispanic communities’ political influence – they found that as the share of the Hispanic population in a Census tract increases, so does the number of water vending machines.

“Profits of Distrust” also presents evidence that distrust in tap water is contagious.

Teodoro said that tap water failures in cities like Flint, Michigan and Jackson, Mississippi – both majority Black cities with high poverty rates – signal to people in communities with similar demographics that their own tap water might not be safe.

“If you are poor, if you are Black or maybe just non-white, you see those failures and you think, ‘Well, those are institutional failures. Governments are supposed to protect those people. Governments didn't protect those people. I identify with those people, and therefore I have every reason to expect that my own institutions are going to fail me,’” said Teodoro, a professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

With all of that in mind, seeing water vending machines cluster in predominantly Latino or lower-income neighborhoods in San Diego County “is not surprising at all,” Teodoro said, in part because the area’s residents are well aware of tap water failures elsewhere in the state.

“You could go north into the Central Valley of California, and you're going to find lots of places with drinking water in poor condition or failing conditions in communities that are going to have generally high Hispanic/Latino and/or low-income populations,” he said. “So folks who are living in San Diego or Los Angeles or any of the other larger, more sophisticated cities, they have either lived in or know friends or relatives who live in those other places where the systems fail.”

A small number of people interviewed at water stores and vending machines around the county mentioned water pollution – whether locally or nationally – among the reasons they avoid drinking tap water. One woman visiting a water kiosk in the parking lot of a southeast San Diego convenience store cited frequent reports about water pollution in the San Ysidro area among the reasons she supposes filtered water is better for her health.

Livia Borak Beaudin, legal director for the Coastal Environmental Rights Foundation, said it wouldn’t surprise her if water and air pollution from the Tijuana River translated into a distrust of tap water in San Diego’s South Bay.

“The border sewage issue makes people just really hesitant, just very distrustful of government action, because we've mismanaged that issue for decades,” said Beaudin. “So I could see those people saying, ‘I'm going to do everything I can to triple ensure that my water is clean.’”

There could be something to that instinct. Imperial Beach has approximately twice as many water vending machines per person than does San Diego County as a whole.

A Question of Taste

Joe Anthony Perez, right, tends to customers at Aqua Bar in Escondido on October 25, 2024.

Photo by Kristian Carreon for Voice of San Diego

The thing most people who frequent water stores and vending machines have in common – the through line uniting people regardless of ethnicity, education or income – is simple: Taste.

Mike Hunter, a customer of the Aqua Bar in Escondido for more than a dozen years, said he grew up drinking well water on a ranch. He remembers city water in Escondido “always had a chemical taste to it, even when I was little.”

He’s not alone. Twelve of the 18 people interviewed at water stores and water vending machines around San Diego County cited taste among the reasons they buy drinking water from a private alternative. Four people said the appearance of their tap water – a yellow tint, cloudiness or floating particles – prompted them to buy water from a store or vending machine. And previous research suggests that tap water that’s not aesthetically pleasing is more likely to prompt distrust than water that actually violates public health standards.

Not liking the way your tap water looks, smells or tastes can set off a health domino effect, too. Some studies show that people who don’t trust tap water may drink less water altogether or turn to sugary beverages instead.

Pierce and colleagues suggest that focusing more on secondary standards – which apply to contaminants that aren’t harmful, but affect aesthetics and therefore impact whether people believe their water is safe – could help to boost consumers’ confidence in their tap water.

“There is a paradox, in that people tend to distrust their water based on these secondary standards that aren't really enforced,” Pierce said. “But if we were able to actually enforce them and report on them, we could do a lot better to address people's distrust.”

San Diego water agencies are well aware that aesthetics matter. Reed Harlan, who manages Escondido’s municipal water, said that’s why the city uses activated carbon and chemicals called oxidizers in its treatment process.

Escondido hasn’t recorded any violations of federal water standards since 2009. Like every other public water system, it’s required to conduct frequent and rigorous testing. Still, Hunter is concerned about tap water in general, citing contaminants like lead, estrogen and fentanyl. He knows the city puts out an annual consumer confidence report, but he’s skeptical that it’s telling the whole story.

“You do need a filter to filter the filters,” he said.

Other vended water customers are more persuadable.

At a water vending machine in National City, a customer admitted he couldn’t remember the last time he drank tap water, but said he might give it another shot if he learned more about how the local water utility filters the water.

He’s visited the same machine in the parking lot of a strip mall roughly every two weeks for five years. Tap water service maps suggest his preferred machine draws its supply from the Sweetwater Authority.

Quintero, the authority’s general manager, often posts up at local festivals, serving chilled tap water in coolers bearing the Sweetwater logo.

“People just get water and we try to tell them, ‘That’s your tap water. That’s what we get to your house,’” he said.

Some are “a little bit surprised,” he added, to discover they like how it tastes.