Sick and struggling in Coal Country

Binghui Huang wrote this series as a project of the National Health Journalism Fellowship, a program of the University of Southern California's Annenberg School of Journalism.

Other stories in this series include:

What's being done about the doctor shortage in Pennsylvania Coal Country?

The steeple of the now closed St. Katharine Drexel Roman Catholic Church stands out in front of the skyline of Lansford as you enter the borough along Route 209. As doctors and dentists retire in Pennsylvania's Coal Region, there aren't enough younger ones to take their place.

(Photo Credit: Rick Kintzel/The Morning Call)

Pennsylvania Coal Region's industry burned out. What remains are pockets of poverty where sick people get sicker.

Alicia Kachmar was out of Tylenol and her toothache was getting worse by the minute.

“I’d rather cut it out right now with a knife. I’d rather give natural childbirth than feel this pain in my mouth,” she said as she trudged from her home in Lansford, where empty storefronts, abandoned homes and crumbling sidewalks are painful reminders of the Coal Region’s decline, to a hospital about two miles away in Coaldale.

To get there, she has to walk on the shoulder of Route 209 as cars whiz by at 45 mph — or more.

She needed an oral surgeon to pull the tooth out, but the nearest one who accepts her Medicaid was almost an hour away. Kachmar didn’t have a car or money for a cab. Actually, her problems went deeper: She didn’t have a phone.

With her brown hair pulled into a messy ponytail, she walked on the winding road, past the No. 9 Coal Mine museum, against a backdrop of barren mountains.

Alicia Kachmar of Lansford walks along Route 209 in Coaldale to go to nearest emergency room at St. Luke's Miners Campus to seek treatment for a toothache. (Photo Credit: Rick Kintzel/The Morning Call)

Lansford is a densely packed borough of fewer than 4,000 people, close to two similarly sized towns but far from any big cities. From the sky, they look like patches on green and brown earth.

The borough is in the heart of Pennsylvania’s Coal Region, known for the richest deposits of anthracite in the country.

In mines stretching from Susquehanna to Dauphin counties, nearly 5 million tonsof the hard coal have been extracted. Until the latter part of the 20th century, Americans were reliant on the fuel to heat their homes and run their industries.

The region is a study in contrasts. Cutting across mountains, waterfalls and lakes, it’s as flush with beauty as it is with coal. Houses peek out of the green, tree-lined valleys that spawned famous Americans such as writer John O’Hara, actor Jack Palance, musicians Tommy and Jimmy Dorsey, and former Vice President Joe Biden. But violence and disaster also mark the rugged terrain — from the massacre of striking Lattimer miners and the hanging of alleged Molly Maguires in the late 1800s, to the tragic breach of the Knox Creek Mine in 1959.

The industry that once defined and supported the people living there has burned out. In its place are poverty, sickness and addiction.

Kachmar and her fiancé, Travis Litts, are among the many fighting drug addiction in Coal Country. But that’s only one of their many health issues. It’s hard for them to get the care they need because there’s a shortage of doctors, dentists, mental health providers and addiction treatment centers. Public transportation is limited, and they can’t afford to buy a car or hire a cab.

The region is one of Pennsylvania’s sickest, state statistics bear out, and rising health care costs make it hard for clinics and doctors to keep their doors open. Pennsylvania’s rural residents are more likely to die from chronic illnesses, drug overdoses and suicides than people who live in many other parts of the state.

Where life expectancy in Pennsylvania is 78.5 years old, it’s a year less in Carbon County, and only 72 in Lansford, where Kachmar and Litts live.

In Carbon, where the population skews older, the number of heart disease deaths is nearly 20 percent higher than the state average, deaths by cancer are about 24 percent higher and deaths by respiratory disease are more than 30 percent higher, state Health Department data show. Neighboring Schuylkill County sees a similar disparity in those statistics.

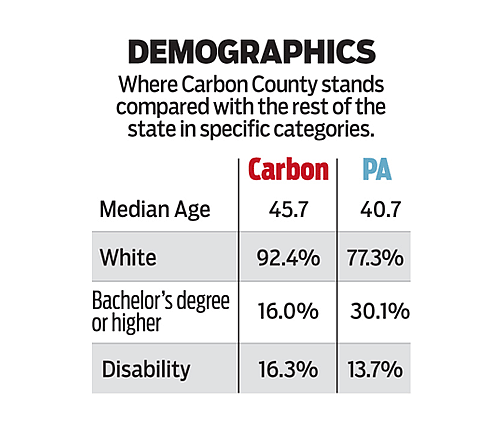

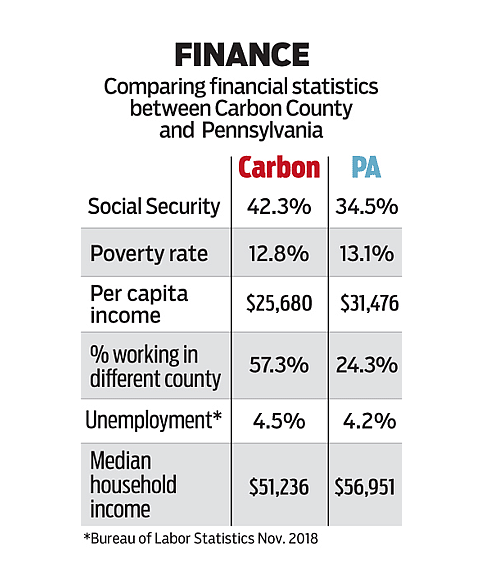

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey Jesse Musto and Gene Tauber / The Morning Call

The Coal Region’s industrial economy left behind potential health hazards. Carbon County alone is home to two Superfund sites — one an old lead-smelting plant in Nesquehoning; the other an old zinc-smelting operation in Palmerton, whose heavy metal emissions defoliated thousands of acres on Blue Mountain.

In September, the Pennsylvania Health Department issued an alert about high lead levels in the air in Palmerton, saying children and pregnant women were especially at risk.

For people who are sick or poor, life in the Coal Region presents a special set of challenges. While they have to travel farther for care, there is no convenient public transportation network. While opioids and meth rip through their communities, there are few treatment options.

As they grow older and sicker, the number of family doctors is thinning out. Change is on the horizon, but it won’t address all the ills that plague the region and people like Kachmar and Litts.

Hitting rock bottom

Kachmar lives in a small apartment with Litts and, sometimes, her three children. They rely on each other for money, food stamps and support. But on this day in September, he’s stuck in jail because he was confused about when he had to appear in court for stealing a few items from a convenience store.

Kachmar had her first child when she was 19. At 28, she has three children and held a job until a few years ago, when anxiety and depression left her unable to work.

She loves Litts and her children and wants a better life for all of them. She began dating Litts after he reached out to her through social media.

They support each other through their worst problems. But like many couples, they bring out the best and worst in each other.

Alicia Kachmar places her head on the shoulder of her fiancée Travis Litts while eating lunch at the Coal Miners Bar & Grill in Lansford. (Photo Credit: Rick Kintzel/The Morning Cal)l

They feel stuck in Lansford. Throughout the town, pictures of local war veterans hang on street corners, and the occasional Confederate flag pops up amid the many American ones.

Patriotism remains strong, even as the American economy has moved on.

“The low life, it’s this, living in this town,” Litts said.

He uses the song “Rock Bottom” by Eminem to make his point.

‘“I’d like to play that for people who don’t understand rock bottom,” he said. “Being hungry and angry enough to steal.”

For people with just enough money to survive, moving to an area with more convenience and opportunity is too expensive.

So the couple focus on getting by, which is more than many of their friends were able to do.

“It’s a lot more than that,” Keith Enlund, a 33-year-old recovering from meth and heroin addiction, said, counting the deaths. “With friends and people that I ran into, you know? Since I got here. It’s got to be up there. Thirty-five, 40?”

Some may consider Enlund lucky. He survived a car crash when he was driving while high, and his parents took him in and cared for him in their Albrightsville home. They drive him to his numerous appointments and AA meetings — sometimes Enlund sees Litts at one. The men met in Carbon County jail.

“Lucky ain’t the word. I’m so grateful,” Enlund said.

Shifting to survive

The health business in rural regions struggles as much as its patients do. It’s hard for rural hospitals and clinics to keep their doors open.

To survive, in 2017 Carbon County’s Blue Mountain Health System joinedFountain Hill-based St. Luke’s University Health Network, whose 14,000 employees work in facilities across eastern Pennsylvania and New Jersey.

The Blue Mountain system, which included Palmerton and Gnaden Huetten hospitals, was losing patients to bigger health networks in surrounding counties and struggling to make enough money to cover expenses.

In neighboring Schuylkill and Monroe counties, smaller hospitals joined Lehigh Valley Health Network, which is based in Salisbury Township and has 18,000 employees.

It’s a common story across Pennsylvania and the country.

More than half of the state’s rural hospitals spent more money than they made in fiscal 2016, and more than 80 percent didn’t make enough money to be financially healthy, according to a 2017 report by the Hospital and Healthsystem Association of Pennsylvania.

The gap between successful hospitals in wealthier regions of the country and struggling hospitals in poor regions is growing.

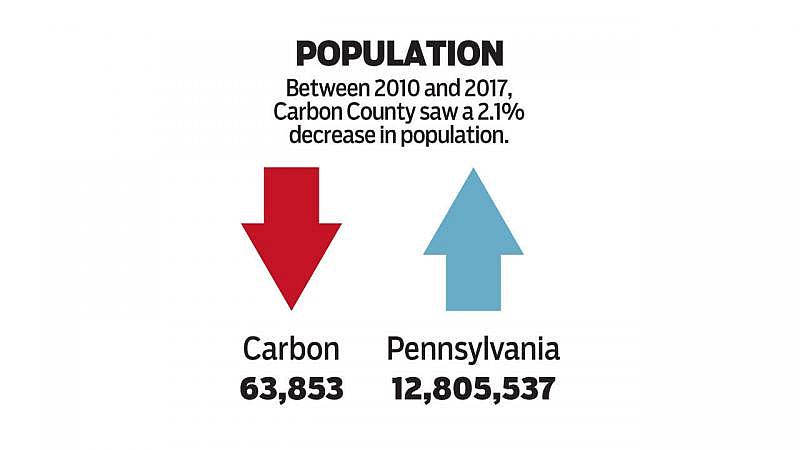

It’s harder for hospitals to make money in rural areas, because of the declining population and higher percentage of people who are older, uninsured, chronically sick and on medical assistance, which reimburses hospitals at a lower rate than commercial health insurance companies do.

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey Jesse Musto and Gene Tauber / The Morning Call

People have left rural areas for better opportunities. And rural economies haven’t recovered from the recession as well as urban areas.

That’s true in Carbon and Schuylkill counties, where employment numbers haven’t rebounded from the Great Recession as they have in neighboring Lehigh and Northampton counties, a December report by Moody’s Investors Service noted.

As people and businesses leave the Coal Region, it gets harder to attract doctors. As physicians retire, they often are not replaced.

That has Jeanne Stemler worried. At 91 years old, she’s been fortunate to have the same physician for decades in Palmerton. But he’s in his 70s and recently joined the St. Luke’s network. She wonders what will happen when he retires.

Keeping busy, Jeanne Stemler, 91, fiddles with one of her paintings as she tries to place it into a frame while in her basement in Lower Towamensing Township. (Photo Credit: Rick Kintzel/The Morning Call)

“He’s near retirement age and he was working on learning the computer system that St. Luke’s has,” Stemler said. “And I said, ‘How are you making out doctor?’ And he said, ‘If I can figure it out, I’ll stay for a little while.’ ”

The bigger hospital networks may bring more stability to the Coal Region’s health care scene.

To compensate for doctor shortages in rural counties, for example, St. Luke’s physicians will travel periodically to facilities in Carbon County, or use video-conferencing to consult with patients there. LVHN specialists also periodically visit facilities in rural counties and use video conferencing.

Last year, St. Luke’s started a medical residency program at its Miners campus, where Kachmar sought care for her toothache. It’s for doctors interested in practicing in rural regions and possibly replacing retiring doctors. The key to its success will be in keeping those doctors after the programs ends.

Most important to Litts and Kachmar is a health clinic St. Luke’s is opening soon that is a short walk from their apartment in Lansford.

The clinic will accept people with commercial insurance, medical assistance and no insurance. It will have a physician assistant or a nurse practitioner, who will handle checkups and sick visits and refer patients to specialists.

Alicia Kachmar places her hand on the shoulder of her fiancée Travis Litts in their Lansford apartment. (Photo Credit: Rick Kintzel/The Morning Call)

In that building, St. Luke’s will also offer physical therapy and counseling.

The center could also make life easier for Carol Loggins, a chronically sick Coaldale woman.

She showed up at the Miner’s emergency room with a digestive problem the same afternoon as Kachmar. She paced around the busy waiting room after checking in, stopping every once in a while to ask the staff when she would be seen.

Like Kachmar, she also left the emergency room without seeing a doctor, because she was tired of the wait after about 45 minutes. She put a towel on her car seat and drove to an urgent care center in Lehighton.

Kachmar and Loggins both used the emergency room for problems that could be addressed at a walk-in clinic, or possibly prevented with regular doctor visits.

When services are thin, emergency rooms become a catchall solution, taxing the system.

Stuck

Kachmar and Litts compare Lansford to West Virginia, which leads the country in health problems.

Like Carbon County, it has a significant working class population and a connection to coal.

“This is like a ghetto type of area, but it’s more like, they use the word ‘hick,’ ” Litts said.

Kachmar laughed knowingly.

“Are you calling me ‘hillbilly’ now?” she joked.

Joblessness is the source of a lot of problems for Litts, who has a high school education and a criminal record.

In Lansford, there are a few restaurants and stores, but he hasn’t been able to get a steady job in one.

“I’m starting to get exhausted because there’s nothing for me to do as far as work,” he said. “You get paroled into this town and it’s like a pit because there’s no public transportation.”

Travis Litts crouches down on the sidewalk along East Ridge Street in Lansford to answer text messages. (Photo Credit: Rick Kintzel/The Morning Call)

Litts says he hauled tree logs for a while, which was labor intensive and sporadic. Eventually, it dried up.

“When I’m working and stuff like that, I feel a lot better about myself,” he said.

Similarly, Keith Enlund needs a job to pay his court fines and become more independent. But he has a fractured back from the car accident, making it difficult to do manual labor.

Driving back from a doctor’s visit last fall, Enlund spotted a road worker directing traffic.

“See, I could do that job,” he said. “But I’d need to sit after awhile.”

The county’s chief probation officer tried to start a workshop to help people with criminal records find jobs, but so few people attended that he shuttered the program. He said he might try again.

Keith Enlund of Albrightsville smokes a cigarette before an AA meeting at Trinity Lutheran Church in Lehighton. (Photo Credit: Rick Kintzel/The Morning Call)

Across the Coal Region, the available jobs tend to be low-paying, in retail or food service, according to thePennsylvania Department of Labor and Industry.

Carbon County’s unemployment rate was at 4.5 percent in November, slightly higher than the state’s.

However, wages in every industry were lower in Carbon than the state average. In the October jobs report, that disparity was $18,000 across the board.

“It’s just you’re not going to get a job where you’re making $40,000 a year, you’re not going to get a job where you get benefits,” said Richmond Parsons, the county’s chief probation officer.

For many, no job is better than a low-paying one, Parsons said, adding that his staff often hears job-seekers say they can’t find work that pays better than the benefits they’re receiving from the state.

“So they’re in this Catch-22,” he said.

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey Jesse Musto and Gene Tauber / The Morning Call

But Kachmar doesn’t get disability checks and is desperate for money.

Every few months, she posts on social media asking if anyone knows about a job opening. If someone responds, she asks her Facebook friends for a ride.

No money means she has no options. She can’t pay her phone bill to call a dentist, buy over-the-counter pain medication or get to a doctor’s office. She can only go to the nearest medical facility: the emergency room.

That September day, Kachmar waited in pain for more than two hours, watching people who came after her go in before her. She rested her head on the flat part of the chair and curled up.

As the sun began to set, Kachmar gave up on the emergency room.

“Hopefully it just goes away,” she said, as she walked back to Lansford.

[This story was originally published by The Morning Call.]