Sickle cell experts say a cure without care jeopardizes the freedom promised by new gene therapies

The story was originally published by the Side Effects Media with support from our 2023 Health Equity Fellowship.

Dr. Lydia Pecker, the director of the Young Adult Clinic at Johns Hopkins Sickle Cell Center for Adults, said ensuring comprehensive aftercare for sickle cell patients is critical

Daniel McGarrity/Side Effects Public Media

Two new, cutting-edge cures for sickle cell disease, a debilitating genetic blood disorder, have been approved on Friday. The sickle cell community is cautiously hopeful as questions around access and comprehensive care loom large.

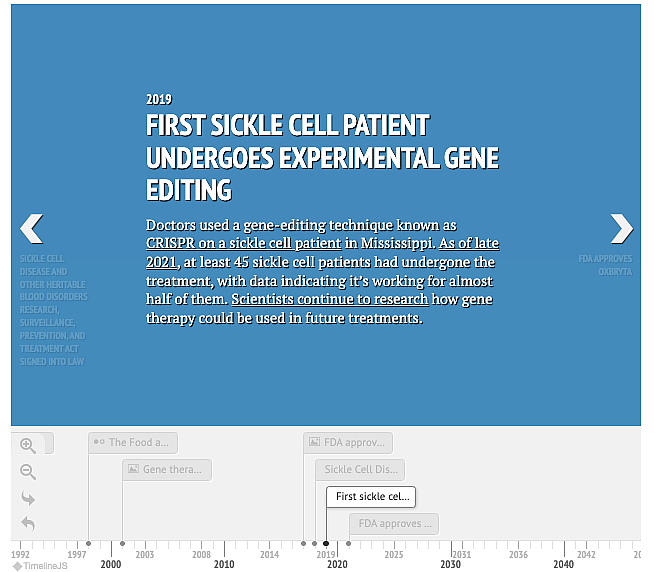

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved Exa-cel, also known by its commercial name Casgevy. It’s a gene-editing therapy that uses the Nobel Prize winning technology CRISPR. The patient’s stem cells would be harvested and sent to a lab to edit the mutated gene and then brought back to the body to start producing healthy blood cells. The other treatment is Lyfgenia, a genetic therapy that doesn’t require gene editing. The treatments have been approved for patients 12 years and older, according to the FDA.

Sickle cell disease affects around 100,000 people in the U.S. –– the vast majority of them are Black –– and millions around the world, mostly in Africa. Around 20,000 patients in the U.S. are likely to be eligible for the new therapies. It’s unclear if and when those treatments will be available to the millions in Africa.

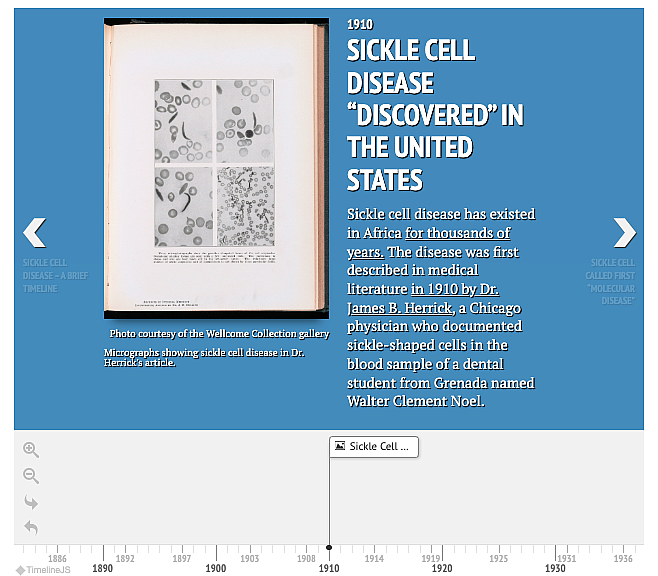

Photo courtesy of the Wellcome Collection gallery

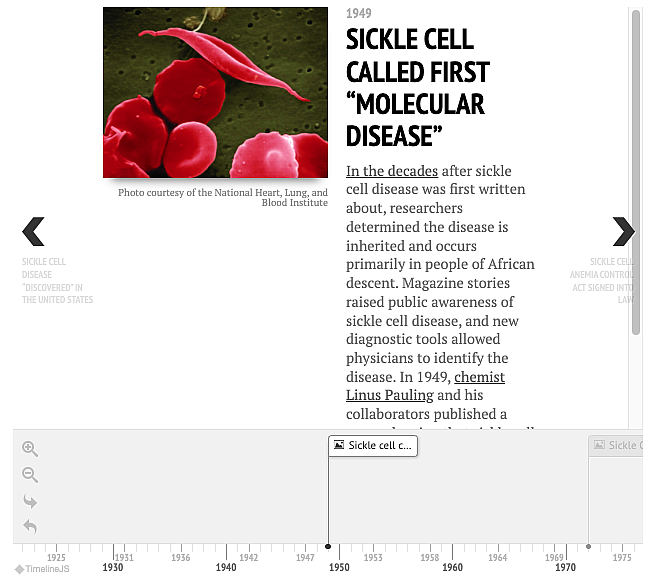

Sickle cell is a debilitating blood disease that affects multiple systems in the body, shortens people’s lives and causes a range of health problems. Its hallmark is excruciating pain crises and health issues including a high risk of strokes and organ failure.

“Sometimes your body feels like it's on fire,” TeVaun Ferris, a sickle cell disease patient, described what pain crises feel like. “Sometimes your body feels like you've just been in a car wreck. Sometimes you feel like you [have] just been lying down on a bed full of nails, and they added another bed with extra nails on top.”

The new therapies promise to cure the disease and alleviate some of the most debilitating symptoms for those who qualify for and can actually access them.

“This is an incredibly dynamic time for this disease, we are finally seeing investments from forest pharmaceutical companies,” said Dr. Lidya Pecker, a hematologist at Johns Hopkins University, who recently co-authored an article in Lancet Haematology on the new therapies and what comes next.

There has been a cure for sickle cell for around three decades known as bone marrow transplant. But not all patients are eligible and the procedure relies on finding a matching stem cell donor, which was not available to many. With these new gene therapies, the patient is their own donor, eliminating a major hurdle.

The new therapies also take an even greater significance when understanding the financial deprivation sickle cell disease has experienced for many decades. Historically, the disease has received a fraction of the federal and philanthropic research dollars compared to other less common blood disorders. For context, cystic fibrosis, another genetic disorder with a majority white patient population, affects around one third of the number of sickle patients but has received 11 times more federal dollars and 100 times more philanthropic dollars than sickle cell disease.

“But gene therapy will not be the right treatment for every individual living with sickle cell disease,” Pecker said.

The new cures require that patients undergo a lot of preparation including large doses of chemotherapy, which raises the risk of cancers and infertility. Pecker said sickle cell disease patients, especially adults, have had to navigate a patchy and lacking system to find care. Fertility preservation, for example, is not guaranteed for them because of the patchwork nature of sickle cell care in the U.S.

And even with a cure, Pecker added, patients who have been living with sickle cell disease for years may have sustained damage, which may be irreversible, to critical organs like the brain, heart, lungs and bones. These patients will need wraparound services.

For sickle cell patients one of the biggest challenges is finding physicians who understand the disease and can help them through it. Despite how complex sickle cell disease is, many patients either see non-specialists or go to the Emergency Department for care due to a shortage of sickle cell specialists.

Then, there is the cost. The new cures come with a hefty price tag of $2.2 million for Casgevy and $3.1 million for Lyfgenia. The majority of sickle cell disease patients in the U.S. are on government insurance and it’s unclear if and how those insurance plans will cover it.

Part of insurance plans’ calculus to determine coverage for services relies on how much a certain treatment would reduce patients’ health care costs in the long-run. Pecker said that the sickle cell patients who get the new treatments need to have the proper aftercare in place to ensure optimal results and lower utilization.

“A comprehensive care model where we really aggressively address complex chronic pain needs can change healthcare utilization patterns for this population,” Pecker said.

Pecker said a cure without proper care “jeopardizes the freedom” promised by these therapies.