Sonoma County reshapes approach to mental health care

This report was produced as a project for the 2016 California Fellowship, a program of the Center for Health Journalism at the USC Annenberg School of Journalism.

Other stories in this series include:

Sonoma County struggles to fill gaps in crisis care for mentally ill

Jail is largest psychiatric facility in Sonoma County

Sonoma County readers share their stories of mental health crisis

Barbara and Denny Bozman-Moss would like to see more treatment options for those with mental illness. Their son is currently is the Sonoma County Main Adult Detention Facility awaiting transfer to Napa State Hospital. (Christopher Chung/The Press Democrat)

The man, shirtless, in dark shorts and white athletic socks, laid face down on the sidewalk in front of a Little Caesars Pizza in west Santa Rosa. He held his hands behind his back, as if they were bound by invisible handcuffs.

Clearly in distress, he rocked slightly on his belly from side to side, calling for help. Several people, including children, walked in and out of shops at the Stony Point Plaza strip mall. Nearly all tried to avoid looking at him, or glanced only briefly as they walked by.

A security guard stood nearby until two police officers showed up. The man, craning his head, begged, “Please put cuffs on me, please put cuffs on me.”

He said people were trying to kill him. He gave the name of a doctor at Aurora Santa Rosa Hospital, a secured psychiatric facility.

“Where am I going to take you?” one police officer asked. “You haven’t done anything wrong.”

Police, however, did find a place to take the man.

He was booked on charges of public intoxication and taken to jail, the largest psychiatric facility in the county following the closure of Sonoma County’s two psychiatric hospitals serving low-income residents.

But the question posed by the police officer during the March 8 encounter illustrates a common dilemma faced by law enforcement officials in Sonoma County and across the nation: What do you do with someone whose mental health crisis does not yet present a major risk of injury or death?

If he had committed a serious crime, police would arrest him without hesitation.

If he were suicidal or threatening to harm someone else, he could be placed on an involuntary psychiatric hold, known as a “5150,” and taken to the local Crisis Stabilization Unit, a psychiatric emergency room in southwest Santa Rosa that provides short-term treatment to people suffering intense mental health crises.

But what about those who are simply scared and need to go somewhere where they feel safe?

“It can be tricky, because if someone hasn’t broken a criminal statute we can’t take them to jail,” Santa Rosa Police Sgt. Dan Hackett said. “And if they don’t meet the 5150 criteria, we can’t take them to CSU (the Crisis Stabilization Unit).”

Like the man in west Santa Rosa last March, a growing number of people with severe psychiatric illnesses are winding up in jail and hospital emergency rooms, The Press Democrat found during a six-month review of local mental health services.

As the mental health system shifts further and further away from a centralized model, which historically placed people in large institutions for treatment, county officials, mental health advocates and medical professionals are now trying to bring all the pieces together to serve more than 20,000 people in Sonoma County estimated to suffer from serious mental illnesses.

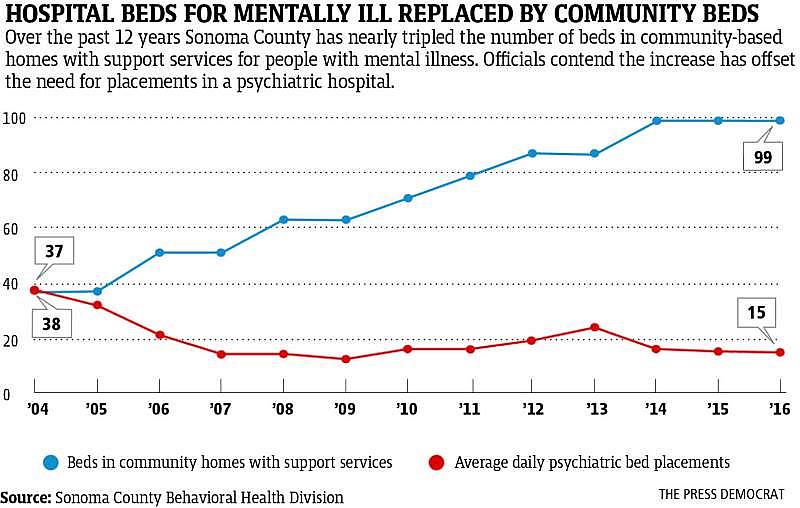

County officials say they’ve taken dramatic steps in recent years to fill the gaps between programs, including the expansion of crisis stabilization services and creating more residential housing with support services for people with mental illness.

But county officials agree more programs are needed. And some advocates say a different model of care is needed, one that treats mental health patients with the same dignity afforded to patients with physical illnesses.

“People keep talking about how the system is broke ... but it’s not. There never was a system,” said Barbara Bozman-Moss, a retired local attorney whose son suffers from schizophrenia and is being treated at Napa State Hospital.

What’s missing, said Bozman-Moss and her husband, Denny, is a place they call CAASI Farm, where people can get a “tuneup” when they’re feeling scared, vulnerable or out of control. The facility would be similar to nonprofit treatment centers such as CooperRiis in North Carolina, Gould Farm in Massachusetts and Spring Lake Ranch in Vermont.

The Healdsburg couple said CAASI Farm — which stands for Community Action And Social Integration — would provide a positive healing environment, free of the drab hallways, thick Plexiglas windows and every other dehumanizing and isolating aspect of traditional psychiatric hospitals and mental health units in jail. Some of Sonoma County’s bucolic settings would be ideal for such a facility, Bozman-Moss said.

The project is among a number of steps underway to address local mental health issues. It’s a countywide effort aimed at enhancing and integrating existing mental health services and patching gaps in mental health care left by de-institutionalization, the decadeslong move toward emptying out government-run psychiatric facilities.

Coordinated care

One key pilot program targets so-called “super-utilizers” who often come into contact with law enforcement and medical emergency personnel. The effort, known as Whole Person Care, would bring together various care providers — including law enforcement, fire departments, ambulance providers, health centers, hospitals, outreach workers and counselors — to provide comprehensive and coordinated care.

In June, the county received a $16.7 million federal grant to fund the Whole Person Care program over the next five years. Michael Kennedy, the county’s mental health director, said the program’s main beneficiaries will be people with severe mental illness, homeless people, drug addicts and people who use emergency services frequently.

The program will have a special focus on veterans, elderly people and those who are being released from jail. It will enhance outreach services in Santa Rosa and expand services to surrounding communities, including Guerneville, Cloverdale, Healdsburg, the Sonoma Valley and Petaluma.

“It allows us to partner with health centers in each of these areas and will also allow us to partner with law enforcement, homeless providers and work directly with the hospitals and the ambulances to really serve this difficult and hard-to-reach population,” Kennedy said. “It really gives me the staff I need on the ground to almost hold their hands and bring them in.”

Barbie Robinson, head of the county health department, said county health workers and their community nonprofit partners have long recognized that a more integrated approach is needed to reduce utilization of emergency services in the county by certain groups, including those suffering chronic mental illness and the homeless.

“This pilot program allows us to really have the resources to test coordination of care and do interventions across the medical and behavioral health system,” Robinson said.

Sharing a hospital

Another effort is underway to create a small psychiatric hospital somewhere between Marin and Sonoma counties, filling the hole left by the closure of two larger psychiatric hospitals in Sonoma County a decade ago.

Kennedy and his counterpart in Marin, Suzanne Tavano, are now looking for a property — ideally in Novato or southern Sonoma County — that could be remodeled into a 16-bed psychiatric health facility, or PHF.

Kennedy said his office is talking with Crestwood Behavioral Health, a statewide mental health services provider that operates similar facilities in Bakersfield, Carmichael, Sacramento, San Jose and Vallejo.

At any given moment, the county has 10 to 12 clients in psychiatric hospitals, while Marin has anywhere from four to six, he said. A 16-bed facility could be used as an alternative to sending people out of the county, in particular to mental health units at St. Helena Hospital in Napa County and Marin General Hospital in Greenbrae.

PHFs offer the same services as psychiatric hospitals but qualify for federal funding. Because they have no more than 16 beds, they are not affected by an arcane rule that blocks federal funding to larger facilities.

Outpatient services

Peg Ledner-Spaulding, LCSW, manager of outpatient behavioral health services poses for a portrait in front on cognitive and dialectical behavior therapy diagrams that illustrate evidence-based tools taught to help people recover from mental illness, at the St. Joseph Health Santa Rosa Memorial Hospital Outpatient Behavioral Health Services clinic in Santa Rosa, California, on Wednesday, August 16, 2017. (Alvin Jornada/The Press Democrat)

There are other promising models emerging in Sonoma County.

St. Joseph Health offers two programs that are producing results for people suffering from intense, short-term psychotic episodes.

Its Outpatient Behavioral Health Services, which has been around for 20 years, treats a whole range of mental health issues including depression, anxiety, PTSD, bipolar disorder, substance abuse and schizophrenia.

One program, called Partial Hospital Treatment, is designed for patients who are either transitioning out of inpatient psychiatric care or who need more support than traditional outpatient therapy. It’s an all-day program that runs four or five days a week.

A second service, the Intensive Outpatient Program, is for patients who have been a little more stabilized but may need additional therapeutic treatment. It is offered three half-days a week and also includes evening groups.

The programs are “safety-net” services aimed at those whose symptoms are worsening to the point where they can no longer function and their daily life is beginning to diminish, said Peggy Ledner-Spaulding, who manages the two programs. Patients are offered group therapy, coping skills, stress management and dialectical behavioral therapy, a type of cognitive behavioral therapy that helps patients change unhealthy thinking patterns and destructive behavior.

“These are evidence-based treatment models that are shown to be very effective for treating mental health issues in a short amount of time,” Ledner-Spaulding said.

For one 73-year-old Healdsburg resident, who asked to remain anonymous, the outpatient center has been a “godsend,” helping her deal with the major clinical depression she was diagnosed with in 2014. The patient just completed an eight-week cognitive therapy program.

“It was very helpful for me to have the structure of having a place to go three times a week and to learn very practical ways of identifying the difference between a thought and a feeling,” she said. “It’s important because so many people believe that thoughts are true and they may not be. Just because you have a thought that you’re a bad person, that may not necessarily be true.”

Ledner-Spaulding said a large majority of people who are struggling with substance abuse or other addictions have an underlying mental health issue, whether it’s PTSD, anxiety or bipolar disorder.

“They are self-medicating their emotional pain in an effort to try to cope,” she said. “We try to teach them functional coping skills and how to manage stress in their lives through learning life skills.”

Mental health farm

For Barbara and Denny Bozman-Moss, a therapeutic mental health facility in a rural setting would be an ideal complement to the county’s expansion of services.

Bozman-Moss said she first started thinking about the idea of a mental health farm in late 2013 and the following year conducted a great deal of research around the subject. She and her husband then put together an advisory group in spring of 2015 and have been lobbying for local support ever since.

She recently filed for tax-exempt nonprofit status for the CAASI Farm Foundation and has begun preparing promotional material highlighting the project, as well as trying to identify seed money from a local donor. The couple is putting together a business plan with the help of a local economist with expertise in land use planning, a necessary step before beginning fundraising.

Most of the properties they’ve looked at in Sonoma County that are under 200 acres run in the neighborhood of $5 million. The capital improvements, which may include the build-out of a farm and housing, could be another $5 million, Bozman-Moss said.

Bozman-Moss hopes to tap into private insurance as well Medi-Cal to make the facility more accessible to residents of all income levels.

The couple envision a place where clients can receive animal and art therapy, where they can work on the farm and make products that can be sold at local stores and markets. But most importantly they see an opportunity to create a supportive community for those with mental illness, and to help integrate them into the larger community.

“It takes community. People need to be interconnected,” she said. “One of the things that happens to people with mental health and addiction problems is they isolate, and part of that is because of stigma. They feel the stigma themselves and part of it is because of people’s prejudice.”

She said she’d like to help people at the farm develop the skills and tools to re-enter society and to put clients on a healing track where they can manage and even overcome their illness in a larger system of care that is free of stigma, just as with other illnesses like diabetes or heart disease.

She said she’s gotten nothing but positive feedback from everyone in the county. She’s even pitched her idea to former U.S. Rep. Patrick Kennedy, the nephew of President John F. Kennedy and son of the late Sen. Edward Kennedy.

Insurers play key role

Jacob Shivers, 8, with his mother, Melissa Ann Shivers, at their home in Northeast Philadelphia. Jacob tried to wake up his classmate Lucas Sims after he became "unresponsive" during story time at Loesche Elementary.

Considered one of the nation’s leading mental health advocates, Kennedy recently visited the North Coast to give a keynote speech at a statewide mental health conference held in Santa Rosa.

While creating more community-based treatment facilities is part of the solution, Kennedy insisted the problem will not be fixed until health insurance companies start covering more treatment. He predicted insurers will not change their approach to mental illness willingly. Instead, he said, they will need to be dragged into court by state attorneys general and sued for violating the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act, a bill he authored in 2008.

The law requires insurance companies to cover mental health services at the same level they do for physical health care, but it had no enforcement mechanism written into it, he said.

“Insurance companies are constantly putting up roadblocks,” he said.

The Kennedy Forum, an organization Kennedy founded in 2013 to promote changes to the mental health and addiction treatment landscape, has begun logging violations of the Parity Act through its Parity Complaint Registry. By documenting how insurance companies are limiting or denying care, it hopes to shape future public policy and legislation.

For Kennedy, the fight for better mental health care is a civil rights issue that began more than 50 years ago when his uncle, President John F. Kennedy, signed the Community Mental Health Act of 1963, which began shifting dollars from psychiatric institutions to community-based treatment programs.

Like so many others who have watched our jails, emergency rooms and streets swell with those suffering severe mental illness, Kennedy said the treatment that was supposed to accompany that transformation has yet to be realized.

“This is no different than diseases like diabetes or cardiovascular disease. We treat them over time and manage them,” he said. “Addiction, depression, other mental illnesses are the same. ... How do we build out a health care system that really incorporates mental health and addiction treatment within it?”

[This story was originally published by The Press Democrat.]