Targeted, Part One

This story is part of a larger series by Neil Bedi and Kathleen McGrory, with support from the Fund for Journalism on Child Well-Being, a program of the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2020 National Fellowship.

Other stories in this series include:

Public interest groups take aim at Pasco sheriff’s data-driven policing programs

Pasco PTA: Use of school data to flag potential criminals ‘unacceptable’

Congressman urges probe of Pasco school data program

Bill aims to curb Florida’s data-driven policing programs

Pasco sheriff’s campaign paid $15,000 to top Sheriff’s Office staffer

Foundation cuts off Pasco schools, citing data sharing

Florida lawmakers take steps to limit school-data sharing

Lawsuit: Pasco intelligence program violated citizens’ rights

DeSantis should consider removing Pasco sheriff, GOP congressman says

Photos by DOUGLAS R. CLIFFORD/Times

Pasco County Sheriff Chris Nocco took office in 2011 with a bold plan: to create a cutting-edge intelligence program that could stop crime before it happened.

What he actually built was a system to continuously monitor and harass Pasco County residents, a Tampa Bay Times investigation has found.

First the Sheriff’s Office generates lists of people it considers likely to break the law, based on arrest histories, unspecified intelligence and arbitrary decisions by police analysts.

Then it sends deputies to find and interrogate anyone whose name appears, often without probable cause, a search warrant or evidence of a specific crime.

They swarm homes in the middle of the night, waking families and embarrassing people in front of their neighbors. They write tickets for missing mailbox numbers and overgrown grass, saddling residents with court dates and fines. They come again and again, making arrests for any reason they can.

Rio Wojtecki, 15, was named a “Top 5” offender by the Pasco Sheriff’s Office. DOUGLAS R. CLIFFORD | Times

One former deputy described the directive like this: “Make their lives miserable until they move or sue.”

At least 1 in 10 were younger than 18, the Times found.In just five years, Nocco’s signature program has ensnared almost 1,000 people.

Some of the young people were labeled targets despite having only one or two arrests.

Rio Wojtecki, 15, became a target in September 2019, almost a year after he was arrested for sneaking into carports with a friend and stealing motorized bicycles

Those were the only charges against Rio, and he already had a state-issued juvenile probation officer checking on him. Yet from September 2019 to January 2020, Pasco Sheriff’s deputies went to his home at least 21 times, dispatch logs show.

They showed up at the car dealership where his mom worked, looked for him at a friend’s house and checked his gym to see if he had signed in.

More than once, the deputies acknowledged that Rio wasn’t getting into trouble. They mostly grilled him about his friends, according to body-camera video of the interactions. But he had been identified as a target, they said, so they had to keep checking on him.

Since September 2015, the Sheriff’s Office has sent deputies on checks like those more than 12,500 times, dispatch logs show.

Body-camera footage shows from deputies interacting with people targeted by the intelligence-led policing program. Pasco Sheriff’s Office

[Click to watch body-camera footage of the deputies’ interactions]

Deputies gave the mother of one teenage target a $2,500 fine because she had five chickens in her backyard. They arrested another target’s father after peering through a window in his house and noticing a 17-year-old friend of his son smoking a cigarette.

As they make checks, deputies feed information back into the system, not just on the people they target, but on family members, friends and anyone else in the target’s orbit.

In the past two years alone, two of the nation’s largest law enforcement agencies have scrapped similar programs following public outcries and reports documenting serious flaws.

In Pasco, however, the initiative has expanded. Last summer, the Sheriff’s Office announced plans to begin keeping tabs on people who have been repeatedly committed to psychiatric hospitals.

The Times shared its findings with the Sheriff’s Office six weeks before this story published. Nocco declined multiple interview requests.

Pasco County Sheriff Chris Nocco Times file

In statements that spanned more than 30 pages, the agency said it stands behind its program — part of a larger initiative it calls intelligence-led policing. It said other local departments use similar techniques and accused the Times of cherry-picking examples and painting “basic law enforcement functions” as harassment.

[Click to read the Sheriff’s Office response to the Times]

The Sheriff’s Office said its program was designed to reduce bias in policing by using objective data. And it provided statistics showing a decline in burglaries, larcenies and auto thefts since the program began in 2011.

“This reduction in property crime has a direct, positive impact on the lives of the citizens of Pasco County and, for that, we will not apologize,” one of the statements said. “Our first and primary mission is to serve and protect our community and the Intelligence Led Policing philosophy assists us in achieving that mission.”

But Pasco’s drop in property crimes was similar to the decline in the seven-largest nearby police jurisdictions. Over the same time period, violent crime increased only in Pasco.

Criminal justice experts said they were stunned by the agency’s practices. They compared the tactics to child abuse, mafia harassment and surveillance that could be expected under an authoritarian regime.

“Morally repugnant,” said Matthew Barge, an expert in police practices and civil rights who oversaw court-ordered agreements to address police misconduct in Cleveland and Baltimore.

“One of the worst manifestations of the intersection of junk science and bad policing — and an absolute absence of common sense and humanity — that I have seen in my career," said David Kennedy, a renowned criminologist at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice, whose research on crime prevention is referenced in Pasco’s policies.

The Times’ examination of Pasco’s intelligence program comes amid a national debate over the role of police in society and calls to reduce funding for law enforcement or replace entire departments.

For years, the program’s inner workings have remained largely out of public view, even as Nocco has touted its merits during debates and community forums. Times reporters combed through thousands of pages of documents, watched hours of body-camera footage and spent months obtaining and analyzing the target list, which had not been previously released.

Pasco is an overwhelmingly white county, and the program did not appear to disproportionately target people based on race.

But juvenile offenders, regardless of race, were an outsized priority for the intelligence program, according to former deputies and a Times data analysis.

Of the 20 addresses visited most by its dedicated enforcement teams, more than half were home to middle- or high-schoolers who were identified as targets.

Pasco County Sheriff Chris Nocco holds a press conference in January in Dade City. OCTAVIO JONES | Times

■■■

BUILDING THE MACHINE

Nocco took over the Pasco Sheriff’s Office in 2011 when his predecessor retired early and then-Gov. Rick Scott appointed him to finish the term.

Nocco was 35 and a newly promoted major who had joined the Sheriff’s Office two years earlier. He had deep ties to Republican politics but far less experience in law enforcement than the outgoing sheriff.

He quickly rolled out a plan to remake the department that sounded like a pitch for a Hollywood blockbuster: Moneyball meets Minority Report.

The intent was to reduce property crime. The agency, which has 650 sworn law enforcement officers and covers a county of roughly 500,000 residents, would use data to predict where future crimes were likely to take place and who was likely to commit them, Nocco told reporters. Then deputies would find those people and “take them out” — thwarting criminal activity before it happened.

“Instead of being reactive,” he said, “we are going to be proactive.”

He later said the approach was not unlike the way the federal government goes after terrorists.

The Pasco Sheriff’s Office wasn’t the only local law enforcement agency trying to predict crime. The Hillsborough County Sheriff’s Office had already started using crime statistics to pinpoint high-crime areas and identify repeat offenders. The two departments discussed techniques, the Pasco agency said in one of its statements.

The Pasco Sheriff’s Office won a $95,000 federal grant to upgrade its computer systems and hired a small team of civilian analysts. At first, the analysts focused on identifying geographic crime trends and gathering information from people in jail, said former Lt. Brian Prescott, who oversaw the team and retired in 2014.

But Nocco wanted to make proactive strategies and intelligence gathering his agency’s central philosophy. All employees were required to take a two-hour course on intelligence-led policing, Prescott said. Supervisors got additional training.

Nocco referenced the program often as he ran for election for the first time in 2012. Some residents appreciated it so much, he boasted in one campaign appearance, they threw deputies a block party.

He won the race and continued building his intelligence machine.

Today, the Sheriff’s Office has a 30-person intelligence-led policing section with a $2.8 million budget, run by a former senior counterterrorism analyst who was assigned to the National Counterterrorism Center. The No. 2 is a former Army intelligence officer.

Twenty analysts scour police reports, property records, Facebook pages, bank statements and surveillance photos to help deputies across the agency investigate crimes, according to the agency’s latest intelligence-led policing manual.

Since September 2015, they have also decided who goes on the list of people deemed likely to break the law.

The people on the list are what the department calls “prolific offenders.” The manual describes them as individuals who have “taken to a career of crime” and are “not likely to reform.”

Potential prolific offenders are first identified using an algorithm the department invented that gives people scores based on their criminal records. People get points each time they’re arrested, even when the charges are dropped. They get points for merely being a suspect.

The manual says people’s scores are “enhanced” — it does not say by how much — if they miss court dates, violate their probation or appear in five or more police reports, even if they were listed as a witness or the victim.

The Sheriff’s Office told the Times that a computer generates the scores and creates an initial pool of offenders every three months. But the analysts go through the list by hand and make a determination about which 100 people should be on the list.

The analysts also work with the command staff to pick “Top 5” offenders, who are thought to be key players in criminal networks, and “district targets,” who the department has enough evidence to charge with a crime. The manual does not say what criteria they use.

Deputies visit the prolific offenders and the other targets as part of their daily responsibilities.

Nocco described the practice as “bothering criminals” to the Council of Neighborhood Associations in 2012.

The manual describes the goal in aggressive terms.

“If the offender does not feel the pressure, if the offender is not arrested when they commit their next crime, or if the offender is left to feel their punishment is menial,” the manual says, “the strategy will have no impact.”

Pasco County Sheriff Chris Nocco touts his intelligence-led policing program in a 2012 campaign video. Youtube

■■■

‘ONE WAY OR ANOTHER’

Inside the agency, keeping the machine humming was a top priority, six former deputies and department leaders told the Times.

“At the end of every shift, they’d want to know how many prolific-offender checks your squad did,” said Chris Starnes, a former lieutenant who oversaw patrol and narcotics units.

Former Capt. James Steffens, who was previously chief of the New Port Richey Police Department, said deputies who didn’t visit enough targets could be removed from special assignments or sent to work in districts far from their homes. Their supervisors could too.

Both Starnes and Steffens resigned from the Sheriff’s Office. Starnes is a plaintiff in an ongoing federal lawsuit that accuses the agency of pushing out employees who criticized specific policies, including the intelligence program. Steffens is also suing the agency, alleging racial discrimination, retaliation and defamation. The Sheriff’s Office denies the claims.

Former Lt. Chris Starnes said he was repeatedly asked about his squad’s prolific offender checks.DOUGLAS R. CLIFFORD | Times

Former Capt. James Steffens said deputies who didn’t focus on the intelligence-led program could face repercussions. DOUGLAS R. CLIFFORD | Times

Some deputies — those on Strategic Targeted Area Response teams, or STAR teams — were dedicated to the program’s objectives. Among their assignments: to “hunt down” the targets, according to a post the Sheriff’s Office made on its Facebook page in 2017.

Later in the post, then-STAR team Deputy John Riyad described the allure of being on the team: “I want to go out and find people to arrest so we can prevent those crimes from happening.”

The job included “intensive monitoring,” as the agency’s strategic plan described it. Email reports recount STAR deputies driving by targets’ homes, hunting for intel. They spotted an orange mountain bike outside one young offender’s house and checked to see if any bicycles matching that description had been reported stolen. (None had.) They found another young offender riding his scooter in front of his residence on the county’s east side.

“He has cut his hair, which is now short,” a deputy wrote in an undated report. “He advised after the summer break he will be going to 9th grade at Schwettman (Education Center). He claimed not to be associating with any of his old friends.”

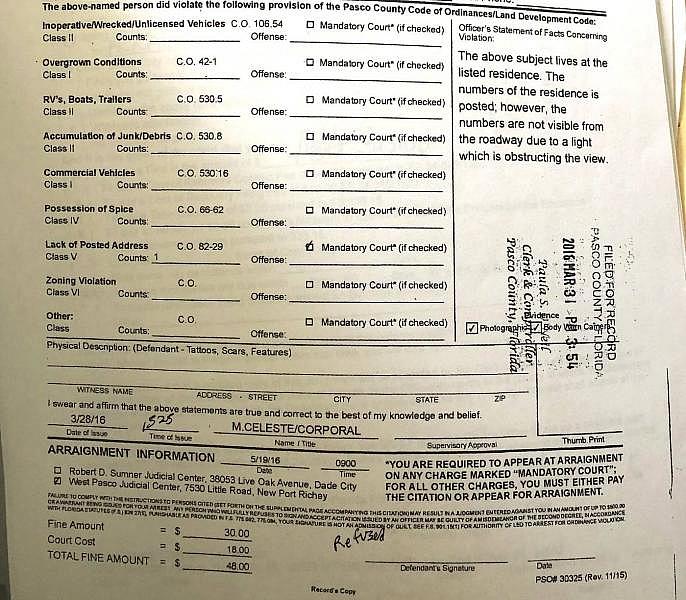

The father of one Sheriff’s Office target was fined over the numbers posted on his house. The numbers were there, the document notes in the top-right, but a nearby light made them hard to see. The form indicates the father had to attend a mandatory court hearing. Pasco Sheriff’s Office

It also involved “directed harassment,” former STAR team Cpl. Royce Rodgers said in an interview with the Times.

Rodgers, who also resigned from the Sheriff’s Office and is a plaintiff in the lawsuit with Starnes, said his captain ordered him to make the contacts aggressive enough that targets would want to move.

Rodgers and his team would show up at people’s homes just to make them uncomfortable, he said. They didn’t always log the contacts in the agency’s official records. He recalled parking five patrol cars outside one target’s home all night and visiting some as many as six times in a single day.

“Those associates might have nothing to do with the offender,” Rodgers said. But as long as the analysts listed them in the system, “we’d harass them too,” he said.They would do the same to targets’ friends, relatives and other “associates,” he said.

If the targets, their family members or associates wouldn’t speak to deputies or answer questions, STAR team deputies were told to look for code enforcement violations like faded mailbox numbers, a forgotten bag of trash or overgrown grass, Rodgers said.

“We would literally go out there and take a tape measure and measure the grass if somebody didn’t want to cooperate with us,” he said.

Rodgers said people sometimes would fail to pay the fine, which would result in a warrant being issued for their arrest.

“We’d get them one way or another,” he said.

Rodgers said the tactics made him and many of his colleagues uneasy. He thought the strategy was both ineffective and unethical, he said. But when he raised concerns, he said, a supervisor threatened to strip him of his rank and send him back to patrol.

■■■

LATE-NIGHT VISITS AND CODE CITATIONS

In interviews with the Times, 21 families targeted by the program described deputies pounding on their doors at all hours of the day and night.

Nearly half said deputies sometimes surrounded their homes, lined their streets with patrol cars or shined flashlights into their windows.

Nine said they were threatened with or received code enforcement citations.

Four said they seriously considered moving. One did.

Two adults whose teenage children were targeted had no complaints about how the Sheriff’s Office had treated their families. Both said they were having trouble with their children and appreciated deputies stepping in. Another father said he was surprised but not bothered that deputies checked on his teenage daughter.

All of the others called the tactics unhelpful or unbearable.

During one prolific offender check, deputies shined flashlights into Sheila Smith’s home and peered into her windows when she wasn’t home. Pasco Sheriff’s Office

Sheila Smith was among them. Deputies showed up at her home in Land O’ Lakes over and over in 2017 and 2018 looking for her teenage son, even though

Their fifth visit was on Jan. 11, 2018, at 10:32 p.m. Smith stepped outside in a bathrobe and explained the situation. “He’s already under supervision,” she told the deputies politely, according to body-camera video of the encounter. “It’s not necessary for y’all to come here anymore.”he was under court-ordered house arrest at his grandmother’s home in Hillsborough County, she said.

Deputies came by looking for her son at least three more times after that, the dispatch log shows. Another time, they put her husband, Vaughn Sr., in handcuffs and loaded him into the back of a cruiser, she said. They later said they had mistaken him for his brother and let him go.

In one of its statements to the Times, the Sheriff’s Office said that the incident had nothing to do with intelligence-led policing and the deputy had apologized for the confusion. But Vaughn Smith Sr. said the visit had started as so many others had: with the deputy asking about his son.

The Smiths said it was obviously harassment. They called a lawyer and considered moving out of the county, they said. They stayed only because they own their home.

Sheila Smith was visited repeatedly by Pasco deputies looking for her son. Each time, she told them he lived in a different county. DOUGLAS R. CLIFFORD | Times

The deputies didn’t only go looking for the targets themselves.

They grilled a 25-year-old woman at the Dunkin’ Donuts where she worked in September 2019 and watched her as she sat outside the building two days later, Sheriff’s Office records show.

The woman had no criminal history beyond traffic offenses. But her boyfriend was a target, and the deputies were trying to find him.

When deputies returned a third time that week, the woman said she and her boyfriend had broken up and complained that the deputies were harassing her, according to their notes. The deputies later confirmed the man they were looking for had left the state with a different woman.

People who were targeted said the checks lasted for months.

Dalanea Taylor was arrested 14 times before turning 17, mostly for burglaries and stealing cars. She went to prison, was released and stopped breaking the law, she said. But deputies kept showing up at her home. They’d ask who she was hanging out with, what she knew about certain people, if she was in a relationship.

Taylor, now 20, wouldn’t answer, she said. It felt inappropriate.

Once, after Taylor posted a photo with a male friend on Facebook, deputies asked about the friend. Later, she said, a deputy followed her in a patrol car as she walked down her street.

When deputies knocked on her door at 7:32 a.m. on New Year’s Day 2018, a family friend implored them to ease up. By then, Taylor had been out of prison for nine months and had not been re-arrested. The deputies said they would not stop monitoring her for a “couple of years,” according to their notes on the conversation.

“She advised she’s staying out of trouble,” they wrote. “She is pregnant and is expecting in June.”

Dalanea Taylor, now 20, pictured with her young children, Liberty and Freedom. She felt uncomfortable with deputies’ questions about boyfriends and male friends. DOUGLAS R. CLIFFORD | Times

Rio Wojtecki, the 15-year-old who deputies checked on 21 times, said the constant visits made him anxious. One night in January, a few hours after deputies had visited, Rio had trouble breathing and collapsed on the bathroom floor. His mother called an ambulance. Later, an emergency room doctor said anxiety was likely to blame.

In one of its statements to the Times, the Sheriff’s Office said Rio had been named a “Top 5” offender because of his “criminal network and associations.” The agency also said he is in a gang, citing criminal intelligence, but would not elaborate. He and his mother denied the allegation.

Rio wasn’t the only person in the family who felt harassed. Three deputies question Rio Wojtecki’s sisters in late 2019. Pasco Sheriff’s Office

One night, deputies showed up at the house when Rio’s older sisters were home alone. His 19-year-old sister, KayLee, explained that Rio was with their mother at her office and went back inside.

Deputy Thomas Garmon knocked on the window and pounded on the door.

“KayLee!” he yelled, according to his body-camera video. “You’re about to have some issues.”

When she opened the door, Garmon threatened to write her a code enforcement citation for not having numbers posted on the house or mailbox unless she let them search the home for Rio. She insisted there were numbers on the mailbox but ultimately let a deputy in.

A few months later, deputies gave Rio’s mother two tickets: one for not having numbers on her house and one for a broken-down car in the driveway. She had to go to court and pay $100 in fines.

Rio Wojtecki continued to be checked on by sheriff’s deputies during the coronavirus pandemic.DOUGLAS R. CLIFFORD | Times Denice Wojtecki, Rio’s mother, had to go to court to pay $100 in fines in February. DOUGLAS R. CLIFFORD | Times

■■■

‘HOW CAN WE GET THIS DUDE?’

Many of the visits were polite, according to interviews with the program’s targets and body-camera footage of the interactions. But as deputies came back repeatedly, some of the interactions turned combative — and had serious consequences.

Rodgers, the former STAR team corporal, said he and his team would look for reasons to make arrests. Once, they spotted a teenage target through the window of his home. Another teenager was there, too, smoking a cigarette. Both refused to come outside, and the target’s father, Robert A. Jones III, wouldn’t make them.

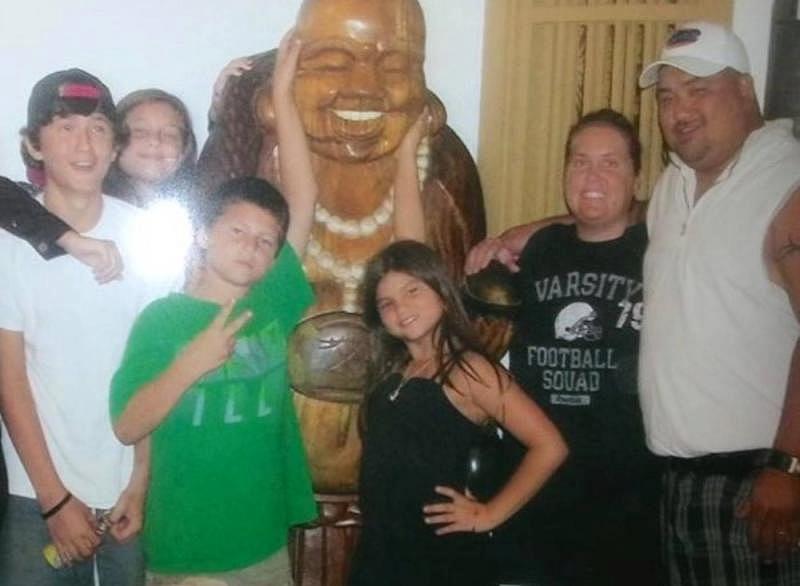

Robert A. Jones III with his family at a restaurant in 2015. Jones and his son (left) were targeted by the Sheriff’s Office in 2015 and 2016. Courtesy of Robert A. Jones III

“We couldn’t get the kids,” Rodgers recalled. “So we arrested the dad.”

Deputies charged Jones with contributing to the delinquency of a minor and resisting an officer.

The charges were dropped. But nine days later, deputies arrested Jones again, this time for missing a court hearing for a code enforcement citation he said he never received. Deputies arrested Jones a third time less than three months later, saying they found a small amount of marijuana in his house and truck.

“It was like a gang,” Jones told the Times. “They were like, ‘How can we get this dude?’ ”

The new charges against Jones — marijuana possession and child neglect — were also dropped, but not before the Sheriff’s Office posted the details of the arrest on its Facebook page.

Jones moved his family to a motel to get away from the harassment, he said. They later moved to Pinellas County.

Other families had similar experiences.

Deputies went to 14-year-old target Da’Marion Allen’s house before school one day last October to ask about a car theft they thought he was involved in. While they were there, they arrested his 53-year-old grandmother, his 28-year-old uncle and a 20-year-old female relative.

Several deputies handcuffed Da’Marion Allen’s family members at their front door in October 2019. Pasco Sheriff’s Office

The grandmother, Michelle Dotson, was standing outside when the deputies first arrived. She said she asked them to call Da’Marion’s lawyer. But when Da’Marion came out, she said, one of the deputies tried taking him into custody.

A police report says Dotson grabbed the deputy by his wrist and refused to let go. Dotson denies the allegations. She said the only person she touched was her grandson, who has developmental disabilities and functions at the level of a young child.

Deputies said the 20-year-old relative tried to hit one of them in the head with a decorative vase. Dotson said that when deputies started crowding the foyer, she asked the relative to move the vase so it wouldn’t break.

None of the adults had been arrested before, they said. They all denied touching or threatening any deputies. Their cases are pending.

Da’Marion Allen, who has developmental disabilities and touch sensitivity, is a target of the Pasco Sheriff’s Office. He lives with his grandparents, Michelle and Terrance Dotson. DOUGLAS R. CLIFFORD | Times

Tammy Heilman had the Sheriff’s Office policy explained bluntly to her in September 2016.

Earlier in the day, STAR team Deputy Andrew Denbo had stopped by her house asking questions about a dirt bike he thought her 16-year-old son — a Sheriff’s Office target — bought with stolen money. Heilman was taking her 7-year-old daughter to Girl Scouts. She told Denbo she wouldn’t speak without an attorney present and drove off.

Denbo noticed Heilman and her daughter were not wearing seat belts, according to the police report. He told her to stop, then followed her down the street and pulled her over.

In the report, Denbo wrote that he opened Heilman’s car door and ordered her to get out. She stayed put and called 9-1-1, saying a deputy had hurt her and she needed help, body-camera video shows.

A Pasco County sheriff’s deputy pulled over Tammy Heilman, opened her car door and held on to her arm. Heilman called 9-1-1 for help. Responding deputies pulled her out of the car and arrested her. Pasco Sheriff’s Office

Heilman told the Times she was scared and confused. She said her daughter had been wearing a seat belt until Denbo opened the door and the two adults began yelling at each other.

The video shows a group of deputies yanking Heilman from the car.

Heilman was arrested on charges of resisting an officer, battery on a law enforcement officer and providing false information in a prior conversation about the dirt bike. The police report says she scratched and kicked the deputies who arrested her.

Before she was taken to jail, during a conversation captured on the tape, Heilman asked why she had been arrested. “Because I told you to stop back there and you drove away,” Denbo replied.

On the way to jail, he continued: “Here’s the policy of the agency. I’ll explain it to you so it makes sense. If people themselves or people that live at a house are committing crimes and victimizing the community, then the direction we receive from our Sheriff’s Office, from the top down, is to go out there and for every single violation that person commits, to come down and enforce it upon them.”

Two years later, deputies arrested Heilman a second time, after she opened her screen door into a deputy’s chest. Heilman said it wasn’t intentional. She had a child in her arms and said the door sometimes jams. Video shows her angrily shoving the door open, but then holding it open and telling the deputies they could come inside.

Because Heilman was on probation, she wasn’t offered bail. She spent 76 days in jail. When she was offered a plea deal that sentenced her to one-year probation plus time served, she took it.

She wanted to spend Christmas with her children, she said. But the decision had lasting consequences. She is now a convicted felon. In the two years since, she said, she has been unable to find work.

Tammy Heilman’s youngest daughters are now terrified of the Sheriff’s Office. Her youngest son has also become a target of the department after multiple arrests. DOUGLAS R. CLIFFORD | Times

■■■

‘EVERYTHING THAT’S WRONG ABOUT POLICING’

Fifteen experts on policing reviewed aspects of Pasco’s program for the Times. Five of them reviewed versions of the program’s manual.

They identified some portions of the program that are based on well-established law enforcement philosophies, including problem-oriented and community policing.

But they also pointed to what they described as serious flaws.

They noted that Pasco’s scoring system awards points based on arrests, which can reflect racially biased policing practices and doesn’t take into account whether charges were dropped or the person was acquitted.

Some experts were concerned that people can get points for having been suspected of a crime. There are no rules for what makes someone a suspect. It can boil down to who they know or how an individual detective investigates, said Sarah Brayne, a sociology professor at the University of Texas at Austin and author of a new book on big-data policing.

Ana Muñiz, a University of California, Irvine criminologist who studies gang databases, noted that the manuals don’t include a way for residents to check if they’ve been targeted or to file an appeal.

The system also lets the Sheriff’s Office collect an extraordinary amount of information on people who may not have committed a crime, said Andrew Guthrie Ferguson, a law professor at American University and national expert in predictive policing.

After reviewing the most recent manual, Ferguson said: “It feels like everything that’s wrong about policing in one document.”

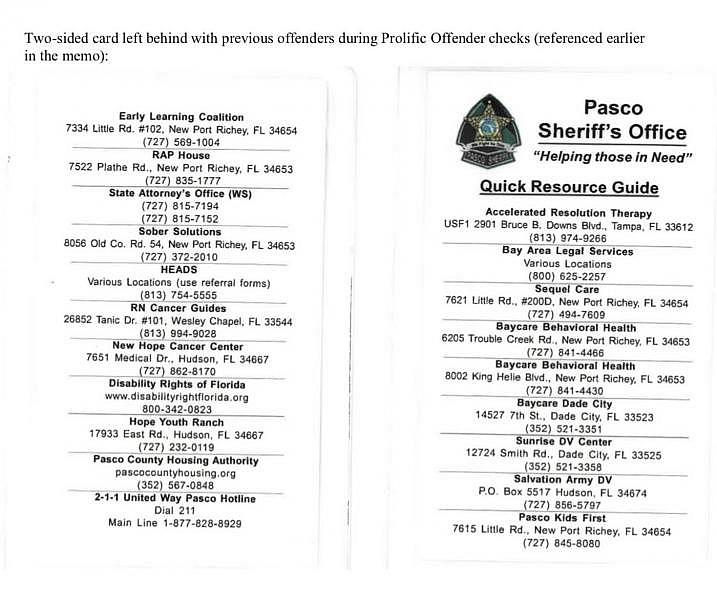

Other experts said the agency’s tactics were unlikely to deter people from breaking the law and added that the program provides little extra help or social services to the people it targets.

A copy of the notecard the Pasco sheriff’s office hands out with local resources. Pasco Sheriff’s Office

The closest it comes is a palm-sized card with a list of 20 local health care providers, nonprofits and government agencies that deputies are supposed to hand out. The cards contain names, addresses, phone numbers and nothing else.

Initially, a half-dozen of the program’s targets said deputies never gave them even that much information. That changed last month. After the Times presented its findings to the Sheriff’s Office, both Rio’s mother and Heilman said deputies came to their houses with printouts of a community resource guide from the local office of the Florida Department of Health.

Ferguson said programs like Pasco’s were popular a decade or so ago. But in recent years, he said, the concept had been largely discredited.

The Los Angeles Police Department used to have a scoring system to identify violent offenders. But critics attacked the program as biased and invasive, and the department’s Inspector General found that half of the 637 people in the database had one or no violent-crime arrests. The department discontinued the program in August 2018.

The Chicago Police Department had its own system that sought to identify people who were likely to be involved in shootings, either as the perpetrator or victim. But the program was unfair and based on outdated and inaccurate data. The agency quietly ended the program in November 2019.

The Pasco Sheriff’s Office said it developed its scoring system with the help of a top expert. The agency said it created the rubric “in concert with the recommendations of Dr. Jerry Ratcliffe, who we continue to partner with on this program.”

Ratcliffe, a national expert on intelligence-led policing, told the Times he hadn’t spoken with anyone at the Pasco Sheriff’s Office “in years and years.” He said his involvement in the program was limited to a two- or three-day training he provided in 2013.

Told this by the Times, the Sheriff’s Office responded that Ratcliffe’s books are required reading, that a Pasco captain contributed to Ratcliffe’s most recent book and that several members of the agency attended a training Ratcliffe conducted this year in St. Petersburg.

■■■

TEENAGERS AS TARGETS

Young people were a major focus of the program, according to records and interviews.

Rodgers, the former STAR team corporal, said his squad “chased almost exclusively juveniles.” Denbo told Heilman, the mother who was arrested twice, that he spent most of his time dealing with kids and their families, according to body-camera footage.

The number of teenagers who were targeted is likely larger than the Times was able to identify.

The agency wouldn’t provide a list that specified when people were added, so the Times started out by excluding anyone who had been arrested after turning 18. That left 88 people. Through interviews, the reporters identified another seven who were targeted as minors and later arrested, raising the total to 10 percent of the list.

About 7.5 percent of people arrested in Pasco County are 17 or younger.

In its statements to the Times, the Sheriff’s Office said the program was designed to address types of property crimes that teenagers often commit. It pointed specifically to a number of auto thefts by young people in neighboring Pinellas County that the Times has reported on extensively.

The statements included an extensive recounting of the criminal records of the juveniles featured in this story. “Just because an individual is 12 does not make him or her incapable of committing crime,” it said of one of the program’s youngest targets.

Kennedy, the John Jay criminologist, called the agency’s tactics “child abuse.”

“There is nothing that justifies terrorizing school kids,” he said.

Other experts pointed to studies showing aggressive policing makes juvenile offenders more likely to reoffend, not less. They said the criminal justice system treats young people more leniently than adults because their brains are not fully developed and they are more likely to be rehabilitated.

The Sheriff’s Office uses juvenile records the same as adult records in its score calculation. Its latest manual encourages deputies to make sure young prolific offenders don’t get the benefits of the juvenile justice system: It recommends they be charged as adults instead of children.

Pasco isn’t the only local law enforcement agency that pays extra attention to young offenders. Several Pinellas County agencies have a joint program to monitor teenagers on court-ordered home detention or probation. But teens must have at least five felony arrests in one year to qualify. It is run in partnership with the state Department of Juvenile Justice and brings social workers and counselors on visits to the teenagers’ homes, Pinellas Sheriff Bob Gualtieri told the Times.

State Department of Juvenile Justice spokeswoman Amanda Slama said her agency had limited knowledge of Pasco’s program and was not involved. She declined to comment further.

Some of the minors who were targeted were especially vulnerable.

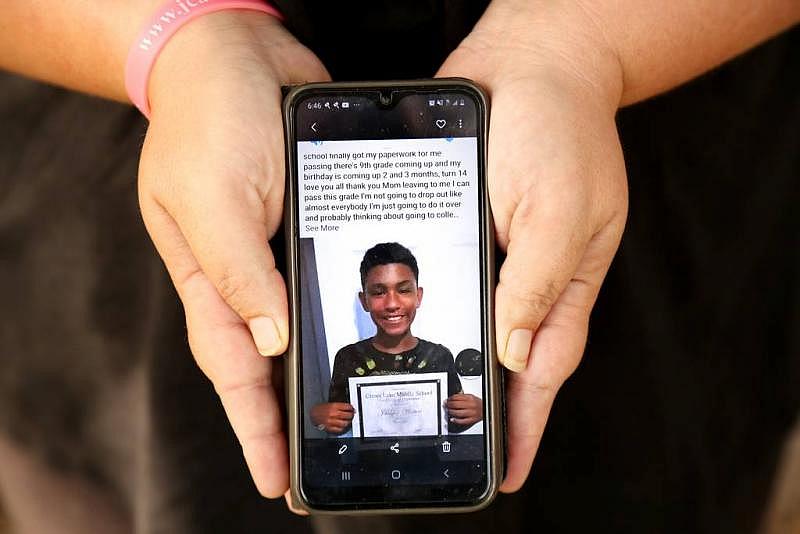

Twenty of the targets were 15 or younger when the list was provided to the Times. Two are 13 today, including Jahheen Winters, who has autism and post-traumatic stress disorder from childhood abuse, his mother said.

Jennifer Winters said her son was repeatedly visited by deputies even though he has autism and post-traumatic stress disorder.DOUGLAS R. CLIFFORD | Times Winters shows a photo of her son, Jahheen, graduating middle school. DOUGLAS R. CLIFFORD | Times

At least three of the targets had developmental disabilities: Jahheen, Da’Marion and Lorenzo Gary, a 17-year-old with autism and mental health conditions, his mother said. Lorenzo was twice found incompetent to stand trial, meaning he couldn’t be prosecuted because a judge found he didn’t understand the gravity of the charges or the potential penalties.

The targeting was sometimes taking place as troubled teenagers worked to get their lives back on track.

Matthew Lott was put on the prolific offender list at 14. He was arrested at least six times in 2016 and 2017, mostly for breaking into unoccupied homes and cars. Deputies checked on him constantly, his mother recalled, sometimes interrupting family movie nights.

But by 2018, after several months at a residential program for at-risk kids outside of Orlando, Matthew started to turn his life around. He returned to Pasco, earned his GED, got a maintenance job at his church and stayed out of trouble, records show. Matthew Lott poses during his graduation from a residential rehabilitative program in 2018. Courtesy of Lachelle Carpenter

Still, deputies showed up at his door. They came one evening that September, when he was supposed to be resting after having his tonsils removed. They came again in October.

“He’s still labeled in our system as a prolific offender, which means he’s going to keep getting checked on,” a deputy told his mom, according to video of the encounter.

Three of Matthew’s close friends said he was afraid the department would find a reason to send him back to jail.

Six weeks after the October visit, Matthew’s body was found behind a vacant building on U.S. 19. His death was ruled a suicide by prescription drug overdose. He had left a short note on his laptop, apologizing and thanking his family and friends.

Matthew’s mother said she wasn’t sure why Matthew took his life. Experts say suicide rarely has a single cause. But two psychologists and a social worker who were not involved in Matthew’s case said the way the deputies treated him could put tremendous psychological pressure on any young person and contribute to a feeling of hopelessness.

Officials at the Department of Juvenile Justice knew Matthew was struggling. They noted in his file at least seven times that he had been cutting himself or had suicidal thoughts.

The Sheriff’s Office acknowledged it had access to a portion of the file that labeled Matthew at risk of suicide. But the department said it would be irresponsible to blame Matthew’s death on its program. It said the program is based on crime data alone, and Matthew qualified.

“Despite our best effort with providing resources, Mr. Lott continued to offend,” the agency said.

Asked what resources it provided, the Sheriff’s Office said it gave Matthew a copy of the resource card, listing 20 other organizations he could turn to for help.

Data reporter Connie Humburg contributed to this report.

The Times reported this story with the support of the Fund for Journalism on Child Well-Being, a program of the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2020 National Fellowship. The reporting was also supported by a grant from the Fund for Investigative Journalism.

[Click here the Sheriff’s Office’s full response]

Need help? If you or someone you know is contemplating suicide, reach out to the 24–hour National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255; contact the Crisis Text Line by texting TALK to 741741; or chat with someone online at suicidepreventionlifeline.org. The Crisis Center of Tampa Bay can be reached by dialing 211 or by visiting crisiscenter.com.

Share a confidential tip: To tell us about your experiences with the Pasco Sheriff’s Office and its intelligence-led policing program, email Kathleen McGrory at kmcgrory@tampabay.com and Neil Bedi at nbedi@tampabay.com. You can also use the encrypted messaging app, Signal, to contact the Tampa Bay Times investigations team at (727) 892-2944. For additional contact options, go to tampabay.com/tips.

[This story was originally published by Tampa Bay Times.]