Three ways valley fever could be elevated as a public health priority

People arrive for the annual Valley Fever Awareness Walk held at the Kern County Museum in August. The walk is one way locals try to spread awareness of the illness.

Henry Barrios/The Californian

Initially, doctors thought Edie Preller had pneumonia, then tuberculosis, or maybe bronchitis. They quarantined her and ran tests. Six months later they discovered that she had inhaled a deadly spore from a fungus that grows throughout the region. The spore caused a disease called valley fever, which spread from her lungs into her brain.

Preller had been an in-home health care worker, taking care of other people who were ill. Then, in her 50s, she ended up in a losing battle for her own life, spending her last three years in and out of a hospital.

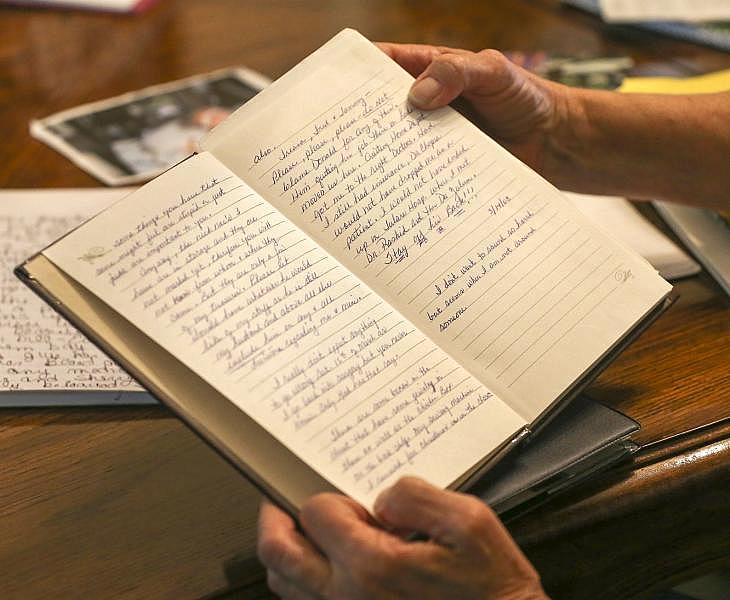

Edie Preller kept a journal as she struggled with valley fever during the last years of her life.

Credit: Henry A. Barrios/The Californian

She described the agony of medical procedures in her journal, “like someone hit a line drive golf ball into a barrel and it ricocheted around.” Another day, all she could manage were the words “very painful.”

When Preller became too ill to write, she asked her family to continue raising awareness of the disease. “Make sure that the public is aware of what valley fever is and how it destroys your life,” she wrote on Feb. 25, 2008. “Mine is not over yet, and I am doing my best to not be another statistic to this disease.” She died soon after at the age of 61.

Who is looking out for future Edie Prellers?

Drive around Tucson on any day and you will see billboards for restaurants, bars, upcoming events and lots of organizations trying to persuade people to do something. Bring a designated driver when you go out drinking. Put down your cell phone in the car. Neuter your dog. Not a single one says anything about one of the most damaging public health threats in Arizona and California: valley fever.

The Center for Health Journalism Collaborative asked experts in social behavior and public health what needs to be done to make the disease top of mind. They focused on three main ideas: Create a simple message that everyone can remember, turn that message into a social movement, and reach out regularly to survey the public to find out if awareness has increased.

Simplicity is key

People can lower the risk of developing valley fever by wearing a mask if working outdoors or by staying inside when it’s windy. There is no vaccine for valley fever. And no treatments completely eliminate the fungus from the body. But early diagnosis and treatment usually lead to better outcomes.

Reaching the general public requires a simple and sustained public awareness campaign on prevention and warning signs.

Public health officials could take a page from the book of the “Click It or Ticket” campaign which encouraged widespread seat belt use. The nationwide effort grew out of a county pilot program in North Carolina funded by the auto insurance industry. Seeing progress, Congress appropriated more than $8 million annually for a national campaign.

As a result, national seat belt use increased 20 percentage points in an eight-year period, the biggest spike in the history of traffic safety, said Madalene Milano, a partner at GMMB, an international communications firm behind the campaign.

To be successful, experts say, awareness campaigns aimed at the general public must carry a consistent message and be deployed at times when people are most vulnerable to disease. For valley fever, that’s in early fall, when the wind begins blowing spores in the air.

Once a message is created, states could use three basic outreach approaches— physician training, resident education and out-of-state education for doctors who might see visitors to endemic areas, said Will Humble, former director of the Arizona Department of Health Services and now executive director of the Arizona Public Health Association.

The message must become a movement

Although government funding was important in the campaign against drunk driving, community organizations took up the banner and made it a top cause, raising private funds to push for tougher laws against driving under the influence and to pay for public awareness advertising. Mothers Against Drunk Driving served as an early example of a powerful public health campaign driven by grassroots organizing.

Valley fever awareness efforts to date have relied largely on government spending. It’s rare enough for Congress to allocate public health awareness funding, Milano said, and even more unlikely that an “orphan disease” like valley fever would capture federal funding for awareness efforts, especially at a time when President Donald Trump’s budget proposal calls for slashing public health spending.

“Money going toward public health issues are dwindling big time, so you have to think beyond government as a source because it’s not as likely to come to fruition,” Milano said.

An ambitious public awareness campaign draws in private donors, interest groups, and local and state agencies.

Rob Purdie, president of the Bakersfield-based Valley Fever Americas Foundation, said his group and others need to become more assertive in making specific requests for government action.

“Nothing’s been asked of them recently. We can point fingers, but nobody has asked,” Purdie said.

A simple public health message has been turned into a movement to combat rising rates of sexually transmitted diseases in Kern County. The county’s STD campaign, “Know your Risk,” has consistent messaging, with public service announcements blaring over radios, airing on television screens and grabbing the attention of passersby on highway billboards. One television commercial features pregnant Kern County Supervisor Leticia Perez, who urges women to seek prenatal care to prevent congenital syphilis.

Public health advocates have lobbied schools for more robust sex education, generated jarring maps detailing how many teens are contracting STDs within certain high school boundaries and have created a long-range plan to reduce infections across the county, which has some of the highest STD rates statewide.

“It’s surpassed a campaign,” said Michelle Corson, a public relations officer for Kern County’s public health department. “It’s a movement.”

A movement made possible by $46,000 in state funding – less than one-thousandth of one percent of the $3.3 billion budget the governor allocated to public health agencies this fiscal year.

Valley fever’s share for awareness? Despite high infection rates, nothing.

“H1N1, Ebola, Zika can all get large special funding, but with valley fever, we’re on our own for awareness funding,” said Matthew Constantine, Kern County’s director of public health services.

Surveys need to check if the movement is working

Awareness campaigns could help prevent misdiagnosis. Arizonans who knew about valley fever before they became infected received a diagnosis sooner than those who did not know about the disease, a 2008 Arizona Department of Health Services study found.

Today, too many patients receive unnecessary anti-bacterial medications because of misdiagnosis when what they need is anti-fungal drugs to combat valley fever, said Dr. John Galgiani, director of the University of Arizona’s valley fever center. The effect of those delayed diagnoses is protracted patient anxiety and expensive, potentially unnecessary tests, he said.

Without surveys to gauge the effectiveness of campaign approaches, there is no way to know whether money is being well spent. As a result, limited funds are being spent without any assessments of whether campaigns are working.

Elizabeth Mulikin holds a photograph of her sister, Edie Preller, at Kaweah Delta Medical Center in Visalia as she battled valley fever. Preller first became ill in October of 2005 but was misdiagnosed until two-years later. She passed away on May 18th 2008.

Credit: Henry A. Barrios/The Californian

Kern County partnered with the California Department of Public Health to distribute 20,000 information pamphlets in high-risk areas in 2014, reaching out to those working in oil and agricultural fields. But they have not repeated those efforts in the three years since.

Kirt Emery, Kern County’s recently retired lead epidemiologist, said he's unsure how well those outreach campaigns worked because the county did not survey those who received pamphlets.

Preller’s sister, Elizabeth Mulikin, does her own type of survey. She asks everyone she can what they know about the disease and its symptoms. And she despairs about widespread ignorance about the disease. She does not want to see others suffer or even die needlessly because they missed opportunities for early diagnosis and treatment.

“My best friend doesn’t even know,” Mulikin said, adding that some of her friends who attended a valley fever awareness walk in Bakersfield last year thought the disease was a variation of the flu.

When that happens, she takes out a photo of her pale sister in the hospital, head flung back, tubes protruding from her body.

“This is valley fever,” she tells them. “It has to stop.”