Valley of contrasts

This reporting was done through USC Center for Health Journalism California Fellowship.

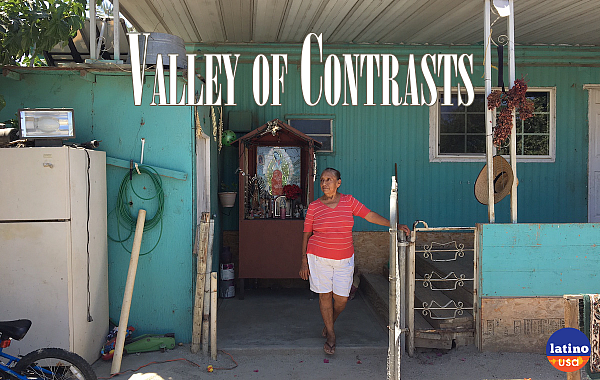

Featured Image: Antonia Cereijido/Latino USA

In most of the country, when someone says they are going to Coachella it means they are going to the incredibly popular music festival where girls wear jean shorts and flower crowns. But for many who grew up in the Coachella Valley in California, their experience has nothing to do with EDM music or partying.

Castulo Estrada grew up in Oasis, a mobile home community on the east side of Coachella. The way he describes it, Coachella is divided into two parts: the west side and the east side. On the west side, there are beautiful homes with large front and backyards. Fifteen percent of all golf courses in California are there, and it tends to be predominantly white. On the east side, you find the mobile homes of the mostly immigrant Mexican and Mexican American communities who go to the west side to do landscaping and house cleaning, or they work in agriculture. The differences between the two sides are stark but there is one difference that has a particularly harsh health impact: access to clean water.

While the westsiders have pools, golf courses and sprawling lawns—all which require a lot of water, there are parts of the east with up to ten times the safe levels of arsenic in their water. For a long time the issues of the eastern Coachella Valley haven’t been a concern of the local water agencies. Many of the people without access to water are in unincorporated areas. But in 2014, civil rights lawyers threatened to sue the Coachella Valley Water District, or CVWD, because for years they held their elections at-large. This meant that the whole district voted on all of the members, and so they tended to be white and come from the predominately wealthy area. So the board voted to adopt district divisions —meaning that each part of the district would elect their own representative.

It is when this change happened that Castulo Estrada’s friends and neighbors encouraged him to run for office. He was young — in his late twenties — but he proved to be a solid candidate. He has a civil engineering degree and had worked in the city’s utilities department. That fall, he became the first non-white member of the CVWD. Since he understands intimately the problems surrounding water distribution in Coachella, he created a CVWD task force whose sole purpose is to solve this problem.

Special thanks to Catherine Stifter, Michelle Levander and Kyle Garcia.

[This story was originally published by Latino USA.]