Virginia’s pregnant women must travel farther as the maternity care crisis grows. Doulas are stepping in to fill gaps.

The story was originally published in Cardinal News with support from our 2024 National Fellowship and the Fund for Reporting on Child and Family Well-Being.

Alexis Ratliff, 29, with her son Ezekiel, 5, and 11-month-old daughter Eleah Witcher in their Rocky Mount home recently. Ratliff had a doula to help with the birth of Eleah.

Photo by Natalee Waters.

When Alexis Ratliff became pregnant with her daughter at the end of 2022, she knew that wherever she chose to deliver, she’d be driving a long way.

There’s a hospital in Rocky Mount, the small Virginia town where she lives, but no labor and delivery unit. She works in Martinsville, a slightly larger city about 40 minutes away, but the hospital there closed its labor and delivery unit months before.

Ratliff, 29, eventually found a doctor at a hospital in Salem more than an hour away. For each prenatal appointment, she had to take half a day off work, and she quickly used up all her paid time off.

Due to preeclampsia — a life-threatening condition — Ratliff had been induced during her first pregnancy. She wanted a natural birth for her second child, but she eventually decided on an induction, this time in part due to logistics.

“I didn’t want to be induced, but I was OK that we did because I was like, what if I went into labor? I’m an hour and 14 minutes away,” Ratliff said.

Without paid maternity leave and out of PTO, Ratliff saved as much money as she could to take six weeks off work after the birth.

Pregnant women are facing similar tough choices across rural Virginia.

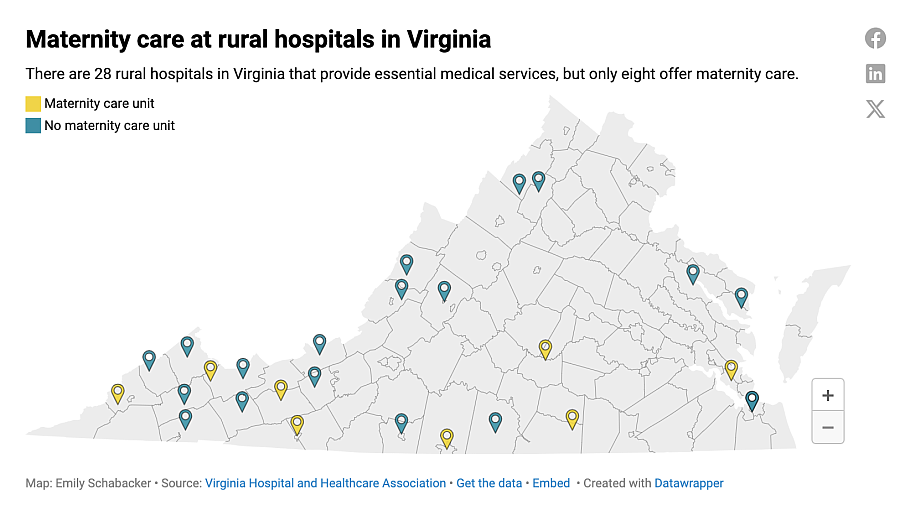

Since 2018, five rural labor and delivery rooms have closed across Virginia, and today only eight of the state’s 28 rural hospitals offer obstetrics services.

Hospitals close maternity wards for a mix of factors: declining births, insufficient Medicaid reimbursement and difficulty recruiting full-time OB/GYNs.

These maternity care deserts disproportionately affect people of color. Black mothers already face higher infant and maternal mortality rates, so the closure of local delivery rooms has sparked concern among health leaders.

“We’re not going to solve the maternity mortality crisis without a real investment. And that investment means that we need to be looking at new models of care that are going to allow people to get the care they need,” said Dr. Makunda Abdul-Mbacke, an OB/GYN who runs a private practice offering gynecology care in rural Southside Virginia.

A legislative task force is investigating the causes of the labor and delivery deserts, work that could inform legislation at the 2025 General Assembly. And as Medicaid reimbursement practices contribute to the closures, both state and federal efforts are underway to expand Medicaid coverage.

U.S. Sen. Mark Warner, D-Va., proposed legislation this year to provide an adjusted Medicaid rate for low birth volume facilities, as well as an overall increase to the Medicaid payment rates for labor and delivery services in rural and high-need urban areas.

The legislation includes a “stand-by” payment that would be offered to rural facilities with low-volume labor and delivery units to help cover costs of staffing.

Del. Mark Sickles, D-Fairfax County, said that the General Assembly has funded some new OB/GYN residencies in rural places in recent years, but the recruitment challenges are substantial.

“We try to keep the Medicaid rates as high as possible. We realize we have to be competitive,” Sickles said. “If the governor put it in the budget I’m almost certain it would be approved. Maybe the General Assembly will look at it more closely now that it’s getting so much attention.”

Meanwhile, local grassroots organizations are filling the gaps. One is Birth in Color, a nonprofit organization that provides doula services and works on advocacy and policy for reproductive justice.

Birth in Color’s advocacy helped Virginia to become the fourth state in the country to bring doula services under Medicaid in April 2022, making the services more accessible to low-income families. And the ripple effects continue: During this year’s General Assembly session, lawmakers mandated that private insurers evaluate adding doula services to the list of essential benefits. Supporters hope that the expansion could happen during the 2025 legislative session.

New models of care

Tamika Tali has been helping women deliver babies for years. She’s helped her family members and her own children through their pregnancies, she’s had five babies of her own, and since 2021, she’s been a certified doula with Birth in Color.

Tamika Tali is a doula with Birth in Color.

Photo by Natalee Waters.

“I’ve seen it all. I’m so normalized to it, you know. I just tell them, send me a picture and they’ve got their phone down there taking pictures,” Tali said, laughing.

As a doula, Tali offers physical, emotional and informational support before, during and after childbirth. She lives in Yanceyville, North Carolina, but takes clients from all around the Southside region of Virginia. And when her clients go into labor, she travels to the hospital to be with them.

Last year, she had a client laboring in Salem and drove the two hours to support her during the birth. Tali stayed for all three days her client was in the hospital.

The mothers in Tali’s care, like Ratliff, have access to her almost all the time. She takes phone calls and answers texts.

The training she received when she joined Birth in Color means she’s able to answer most of the day-to-day questions that expectant mothers have.

She can advise them to drink more water to address headaches or encourage them to go to the doctor when it’s needed. In the doctor’s office, she’s a fierce advocate for them.

But some physicians caution against seeing the expansion of doulas as a long-term solution to the maternal health crisis.

“They’re a part of the solution. They’re a piece of the puzzle, but midwives and doulas don’t do C-sections,” Abdul-Mbacke said. “People feel like there’s all this medicalization of labor, and, you know, we could all just have these natural births and everything would be fine. But we’d be going back to levels of maternal morbidity and mortality of the 1800s.”

Even so, birthing doulas have emerged as a solution for the maternal health crisis by providing personalized support to mothers, especially in underserved communities.

In 2020, Virginia passed legislation to create a state certification for doulas and commissioned a work study on the best practices for bringing doula services under Medicaid. In April 2022, the doula benefit began.

Their presence has been associated with improved birth outcomes, lower rates of cesarean sections and reduced need for pain relief, according to a study published in the National Library of Medicine. Doulas also play a critical role in advocating for mothers and ensuring that their voices are heard and birth preferences respected, which is particularly important for Black and other minority women who face disproportionately high maternal mortality rates.

While Virginia’s infant mortality rates have started trending down, infant mortality for babies born to Black families was 10.4 per 1,000 live births, nearly two times the state rate, according to data from the March of Dimes 2023 report card.

“As Black women, we are looked at as being more tolerant to pain, that we can take more pain than any other race. Doctors sometimes think like this as well as the nurses and staff,” Tali said. “A lot of times our women are given the epidural and stadol [a pain reliever] and left for hours unattended, no matter how many times they ring that call bell. Our voices aren’t heard as loud as those of other minorities.”

One of Tali’s clients, Rachetta Hightower, leaned on her doula when she was misdiagnosed with placenta previa, a condition when the placenta attaches low in the uterus.

The nurse who administered the diagnosis told Hightower that the only way she could safely deliver would be via C-section.

Tali later questioned the diagnosis and encouraged Hightower to talk to her obstetrician at her next appointment. The doctor told her the diagnosis was a mistake. Hightower successfully delivered vaginally, but the anxiety stayed with her through her labor.

“I still had thoughts of am I going to bleed out,” Hightower said. “I already had high blood pressure.”

The high infant and maternal mortality rates among Black families is what spurred Kenda Sutton-el into advocacy, creating Birth in Color to both expand doula services for Black and brown women and to push for policy changes that would improve birthing outcomes for minority mothers.

Bringing doulas under Medicaid has made services more accessible, but the reimbursement rates fall short of the cost of care.

“It absolutely does not reflect a living wage,” Sutton-el said, nor does it provide additional funds for travel.

Doula services billed to Virginia Medicaid can be reimbursed up to $859 for eight prenatal or postpartum visits, plus labor and delivery, according to the Center for Health Care Strategies. Another incentive payment is released if the mother attends her first postpartum visit.

Typically, it costs Birth in Color about $800 for just two prenatal visits with a client, Sutton-el said.

Sutton-el intends to return to the Virginia General Assembly in the coming years to ask for greater reimbursement for the care her doulas provide.

“It was a test project to see if we can get doulas enrolled. Let’s see what the outcomes will look like. … We have a great collaboration with the Medicaid department and so I definitely know that they’re on board to make it better,” Sutton-el said.

Some independent doulas have opted not to accept Medicaid due to the reimbursement rate.

Roshay Richardson provides doula services across Southside Virginia. She also works for the Virginia Rural Health Association as its breastfeeding coordinator.

“Most community doulas who take the Medicaid reimbursement have to work another job on top of being a doula. … You need to make sure your work has an understanding that you need to leave when a client calls,” Richardson said.

Private insurance does not cover doula services, but state legislation passed earlier this year requires the Health Insurance Reform Commission to consider covering doula care services as it reviews essential benefits.

Though the reimbursement is low, Medicaid has significantly increased the accessibility of doulas. Now, about 90% of Sutton-el’s clients use their Medicaid coverage to access doula services.

Reimbursement practices can lead to closures

Rural obstetrics units across the U.S. have been jettisoned for financial reasons. The closures have primarily hit low-income, rural communities where births have declined.

When Sovah Health closed its labor and delivery unit in Martinsville in 2022, hospital executives cited declining birth rates in the region. Deliveries at the hospital had declined by 60% in the previous seven years, health officials said.

The number of deliveries is one predictor of the sustainability of a labor and delivery unit, according to Steve Heatherly, market president of Sovah Health. With more births, hospitals can spread fixed costs, such as salaries and equipment, over a larger number of patients, making the unit more cost effective.

Since the Martinsville closure, Sovah Health’s Danville hospital is the only one delivering babies for at least five Southside counties.

In 2023, the Danville hospital had 771 deliveries, a 20% increase from 2021, Heatherly said. Of those, 625 were Medicaid births, 131 were covered by private insurance, two were paid by Medicare and 21 were self-pay.

Another common indicator of a labor unit’s success, according to some providers, is the mix between patients with private insurance and those with Medicaid.

Medicaid reimburses hospitals at a fixed rate for obstetric care. The rates are intended to cover the cost of care, but frequently they fall short of what hospitals say are the actual costs.

States set Medicaid rates, so they vary widely, but are typically much lower than those of private insurance. In low-income communities where many of the residents are on Medicaid, the cost of providing care to pregnant people usually outweighs the revenue generated, meaning childbirth simply isn’t profitable at smaller hospitals.

The highest possible reimbursement rate in Virginia for the pregnancy, birth and the first postpartum visit comes to about $2,300, said Dr. Laura Peyton Ellis, an obstetrician who spoke to Virginia legislators during a July rural health committee meeting. This rate covers hospital fees and resources.

Private insurance reimburses at a level that’s about 150% to 166% of the rate that's paid by Medicaid, she said.

Cardinal News requested more specific Medicaid and private insurance reimbursement data from the Department of Medical Assistance Services and the Virginia Association of Health Plans. A DMAS representative said each birth is situationally dependent and there are too many factors at play to provide accurate reimbursement rate data. The Virginia Association of Health Plans said it could not provide information due to antitrust concerns.

Hospitals with a mix of payers, both private and Medicaid, are better able to balance the losses.

Medicaid finances about 42% of all births in the United States, but in Southside Virginia, many more women rely on the public health insurance.

In Martinsville, for example, 76% of births in 2022 were financed through Medicaid, according to data from the Virginia Department of Health’s Maternal and Child Health dashboard, a new tool designed to track health outcomes. In Danville, the nearest city to Martinsville with maternity care, nearly 85% of births in 2022 were Medicaid births.

“In the 17 years or so since I’ve been down here, the community has gotten poorer and that's going to reflect in the reimbursements paid to the hospital,” said Abdul-Mbacke.

Abdul-Mbacke provided obstetrics care at Sovah Health Martinsville until it closed its delivery room in 2022. She now runs a private practice in rural Southside Virginia offering gynecology care.

“When I came here there were seven to eight OB/GYNs all active, all doing surgeries. It’s a shame, and the health of the community is definitely decreasing,” Abdul-Mbacke said.

Without OB/GYNs in the area, ability to access prenatal care and the number of prenatal visits has decreased over the past two years, she said.

Taylor Platt, a health policy manager with the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology, said that rural hospitals face numerous challenges when it comes to the payment systems for obstetrics services.

“There’s a lot of problems with how we pay for obstetrical services that can really impact these smaller rural hospitals,” Platt said.

All obstetrics care — from the first visit to confirm the pregnancy to the initial postpartum period — is bundled for Medicaid reimbursement purposes. It’s not until after the first postpartum visit that a provider can bill for services, encompassing nearly a year's worth of care, Platt said.

There are exceptions when multiple doctors provide care at different stages of the pregnancy, according to a 2022 Virginia physician practitioner manual. For example, if a patient sees one provider for prenatal care but delivers with a different doctor, each one can submit a claim. However, both providers must wait until after the first postpartum visit to do so.

In Virginia, Medicaid reimburses at a rate that aligns with the recommendations of ACOG, though that doesn’t mean that the rates cover the complete cost of care.

Some states have voted to increase the Medicaid reimbursement beyond the recommended rate, Platt said. Yet it’s still unclear if the change has helped to keep rural hospital OB units open.

Trying to fill the void

When the hospital in Martinsville closed its obstetrics unit, other organizations in Southside Virginia scrambled to help.

Danville-based Piedmont Access to Health Services, or PATHS, took on as many patients as it could, but the transition was stressful, said Tammy Osborne, operations manager at PATHS.

“We were struggling to get everybody in to be seen at their correct timing,” Osborne said.

In the third trimester of pregnancy, patients with typical pregnancies come in for appointments about every other week. People with complex or high risk pregnancies may need to be seen twice a week.

PATHS introduced OB/GYN care at its Danville office in 2019 with three physicians. Since then, the team has expanded to include 12 OB/GYN doctors across its network.

PATHS now has clinics in Danville, Martinsville, Chatham and South Boston, which opened this past March after that town lost its obstetrics unit.

“As a nonprofit, we feel like it is our responsibility to try to meet the needs of the people that live in this area and as long as we are able, we will do OB/GYN. It’s costly, though,” said Marsha Mendenhall, CEO of PATHS.

Its designation as a federally qualified health center gives PATHS some financial cushion, but federal dollars cover only 12% of the organization’s budget, Mendenhall said. Its pharmacy program brings in revenue to help cover the losses in OB/GYN.

For a medical practice to have an obstetrics unit, at least one provider must be on call at all times. For a labor and delivery unit, the department needs to be fully staffed at all hours of the day and night.

Once a maternity unit closes, it’s unlikely that it will ever reopen due to the cost of building up a workforce, Mendenhall said.

Alexis Ratliff makes dinner in her Rocky Mount home.

Photo by Natalee Waters.

Having an advocate

When Ratliff had her first baby, paying nearly $2,000 for a doula wasn’t feasible. For her second child, she was able to work with Tali at no personal cost with Medicaid.

“I really did want somebody else to just help advocate, especially since with women of color the mortality rates are higher, so I was like, anything could happen,” Ratliff said. “My family members never had good experiences up here at these doctors' offices. Even just for regular appointments.”

Tali arranged to meet with Ratliff during her lunch breaks to avoid taking any more time off work.

“I was like, here’s someone that is down to earth. Here’s someone that is actually talking to me and explaining a lot of things. Because when you’re with your doctor, I mean, I think it was like five or seven minutes with each patient,” Ratliff said.

Tali brought essential oils and candles to the birth to help create a calming environment and hunted down the doctors and nurses when Ratliff was left alone for hours on end during labor.

Ratliff had been there for her sister and her best friend when they had their babies, and looking back she now realizes that they would have benefited from a doula, too. The experience meant so much to her that Ratliff has enrolled in the doula training with Birth in Color.

“Before, I just assumed, gosh, this is how [birth] is, you know. And then to have an experience be so, like, no, that is not how it’s supposed to be. This is what it’s supposed to be. It just made me want to advocate for other women around here that are in poverty or lower income,” Ratliff said.

“I want to help those women how I was helped.”

Jenny Stratton with CatchLight contributed to this report. This story is part of a collaborative reporting effort led by the Institute for Nonprofit News' Rural News Network. Support from the Walton Family Foundation made the project possible.