In West Virginia’s ‘Poultry Capital,’ immigrant workers struggle to find the help and support they need

The story was originally published in Mountain State Spotlight with support from our 2023 Impact Fund for Reporting on Health Equity and Health Systems.

Moises Saravia, an immigrant from El Salvador and the pastor of a Spanish-speaking Moorefield church, discusses some of the problems his congregants face in West Virginia.

(Photo by Duncan Slade)

MOOREFIELD — Tatiana had two options after she lost her job in 2020, and both of them broke her heart.

The first was to stay in Honduras, a country where more than half of the people live in poverty. With no new job opportunities, Tatiana knew she and her two young children would struggle to survive.

The second was taking up the offer of a Honduran man who lived in Moorefield — a 2,800-person town in West Virginia’s Potomac Highlands. Over social media, he said there were jobs for undocumented immigrants and offered to pay for Tatiana and a child to join him as a family.

Tatiana chose the second option, and she and her daughter made the 15-day trip by bus and van to Moorefield. Within a few days of arriving, Tatiana started working for a contract company that staffed the production lines in Pilgrim’s Pride’s chicken factory, the largest employer in a town known as the “Poultry Capital of West Virginia.”

At the time, the plant was desperate for workers.

“This was the only option to give my children a better financial situation,” said Tatiana, who is identified by her middle name because she fears deportation.

After a few months, she said the Honduran man became violent, leading Tatiana and her daughter to move out. For two weeks, they were homeless with their clothes in bags, and Tatiana didn’t know how to make ends meet.

“My daughter would cry a lot,” she said. “She would question me a lot, ‘why would you bring me to the United States if I was happy in my country?’”

Over the last three decades, thousands of immigrants like Tatiana have come to Hardy County to work for Pilgrim’s Pride, an arm of the largest chicken producer in the world.

Moorefield houses surround Pilgrim’s Pride’s West Virginia factory.

(Photo by Duncan Slade)

It’s a setup that allows the company to hit profit goals. While Pilgrim’s rarely outwardly acknowledges its reliance on immigrant workers, it frequently lists new immigration legislation or enforcement as potential threats to its business operations in corporate filings.

Many newcomers say they expected the plant to be a path to a healthy, happy life — something that can seem impossible in their homelands.

But when issues come up outside of everyday work, they say there’s few people able to help them out. Moorefield immigrants often struggle to find affordable housing, adequate interpretation services, financial assistance and other resources that could ease the transition to the U.S.

“Every year, it’s not getting fixed,” said Moises Saravia, an immigrant from El Salvador who’s lived in the area for 16 years and is the pastor of a Spanish-speaking church. “Every year, it’s more problems, more problems, more problems.”

Over the past several years, Pilgrim’s has publicized its charitable donations — just under $1 million — to Moorefield. The company helped pay for a “Little Peeps” day care facility, an indoor recreation center next to the elementary school, an expansion of the local park and upgraded defibrillators across the county.

Pilgrim’s newest project — an apartment complex near the factory — is also part of the company’s ongoing local investment, according to plant manager Allen Collins.

“Pilgrim’s understands the responsibility of being the largest employer in Hardy County,” he wrote to elected officials about the project. “The Moorefield processing plant employs more than 1,700 workers and supports many local family-based growing operations.”

Construction of Pilgrim’s new Moorefield apartment complex in November 2023.

(Photo by Allen Siegler)

Pilgrim’s already rents housing units to some of its new employees, but it can charge workers hundreds of dollars more per month than what the federal government says is fair for Hardy County.

The company’s corporate and local offices did not respond to emails, phone calls and a letter with more than a dozen questions related to this story.

Some local government programs and nonprofits have tried to aid Hardy County newcomers with their problems outside the plant. But most have struggled to make inroads with new communities — often because of limited funds or difficulty connecting with people who speak over a dozen different languages.

“There’s a lot of things with the immigrant community, I think, that we don’t have a real good handle on,” said David Workman, the Hardy County Commission president.

Many in the community are still just trying to learn which languages are spoken among Hardy’s frequently-changing immigrant population.

“We really don’t know,” said Susan Knibiehly, chief operating officer of Eastern Action, a social services group based in Moorefield. “We need more information so that we do have things available.”

That disconnect has led former and current immigrant workers to go without benefits they qualify for or medical treatment they need, struggle to pay bills and worry whether they will be able to put food on the table for their kids.

Back in Honduras, Tatiana was a government worker who helped repair the homes of poor residents. But while she was unhoused in Moorefield, she didn’t know who could help her.

“I gave a lot for people and offered many services,” she said. “Here, I think sometimes ‘where’s everything that I have given?’”

It can make her question why she left Honduras, regardless of the persistent poverty that confronted her there.

“I only thought I would change my children’s financial fate,” she said. “I’m here, and I wasn’t able to change it. So I feel the American Dream doesn’t exist.”

Where help falls short

A Moorefield church in front of Pilgrim’s Pride’s Moorefield feed mill.

(Photo by Duncan Slade)

After moving out, Tatiana never returned to the Honduran man’s home.

She said the man had struck her in front of her daughter, an incident that led her to eventually seek a domestic violence protective order against him (Documents show a judge approved an emergency order but denied a permanent one, finding that “the parties testified in contradiction to each other, and allegations do not rise to the level of domestic violence”).

Instead, Tatiana opted to take her daughter to a coworker’s house, where they briefly lived before renting a trailer on the outskirts of Moorefield. She said the landlord charged her $1,000 a month for rent.

“We may have had only eggs, beans, milk, cornflakes,” she said. “But we had something.”

But in late 2022, around the same time Pilgrim’s told shareholders that its U.S. labor shortages were improving, Tatiana and other Moorefield undocumented immigrant poultry workers were fired.

Without a paycheck, Tatiana struggled with her monthly rent. Utility bills sometimes took up every penny she had saved up. One month, after two strangers paid a $70 water bill and a $30 trash bill for her, she remembers bursting into tears.

“I didn’t cry about the money,” she said. “I cried because I knew although I was going through very difficult situations, God provided.”

Even though Tatiana knew there were government programs that help Moorefield residents in tough financial situations, she never sought them out because she worried about being deported.

“I honestly don’t know what I can apply for,” she said.

Katy Lewis, a senior attorney with the nonprofit Mountain State Justice, has seen this issue frequently among people in Hardy County. Over the past year, the organization has tried to build relationships with Moorefield immigrants to help them find a pathway to legal residency or citizenship in the U.S.

Lewis said the nuances of immigration law frequently leave immigrants in a position where they don’t know what aid is available.

“Our immigration system is so complicated,” she said. “Even the most educated person would have a hard time navigating it, let alone a non-English speaking person who may have no literacy in any language.”

And it’s not just the town’s undocumented immigrants who struggle to access help. Two years ago, Erika Perez, a 44-year-old permanent resident from Peru, stopped working at Pilgrim’s Moorefield slaughterhouse to take care of her young daughter.

After quitting, she initially qualified for food assistance from the West Virginia government. But in March of this year, the state denied her claim for the benefit.

For months, Perez didn’t know why she no longer received the aid. The government mailed her some documents, but they were all in English.

“I would call my friend who would have to help me,” Perez said, through a Spanish interpreter. It took her until mid-May to get her assistance renewed.

Saravia, the Salvadorian pastor, sees these types of struggles all the time among his members.

“Everybody in the church, they need more attention,” he said while sitting in front of the wooden pulpit where he leads congregants in songs and prayers on the weekends.

He’s done all he can, from trying to find funding for a congregation food bank to visiting the homes of his sick members.

Last fall, Saravia took a job at the poultry plant. At night, he grabbed thousands of live chickens by their legs and hooked their feet onto an industrial conveyor belt lined with metal shackles.

During the day, he helped his church members. Every week, he would take congregants without cars to see doctors or immigration lawyers in places as far away as Morgantown — a hundred miles each way through the mountains that surround Moorefield. Sometimes, he served not only as a chauffeur but also a Spanish-English interpreter.

Moises Saravia, a pastor from El Salvador, sits inside the Spanish-speaking church where he preaches.

(Photo by Duncan Slade)

This schedule came at the expense of his own health. The more chickens he hung, the worse his shoulder hurt. Saravia rarely had time to make his doctor appointments to monitor his diabetes.

In March, he quit the plant to better care for himself and his church. Now without his salary, Saravia and his wife, who still works at the plant, are nervous about providing for their children.

But both realize the past setup wasn’t sustainable.

“She told me ‘You know what? Take the time right now,’” he said. “‘Try to feel better.’”

Many of his church members came to Moorefield to work at Pilgrim’s and still do. But few people stay in the factory very long.

The most recent census workforce data show that in the first half of 2023, about 500 Pilgrim’s employees had quit or were fired from the factory.

For immigrants who, like himself, have to leave the plant, Saravia sees a lot of them struggle to make ends meet. He said most of his church members are still learning English — and nearly every other employer in Moorefield requires applicants to speak the language.

“There’s only one job,” he said.

‘They deserve the same chance we got’

The Pilgrim’s Recreation Center is beside Moorefield Elementary School.

(Photo by Duncan Slade)

At the center of Moorefield, there are three newly-built basketball courts in the town park; their blue and yellow synthetic surfaces match the high school’s colors. Throughout the county’s public buildings and outdoor areas, a nonprofit replaced old emergency defibrillators with brand new ones.

Pilgrim’s paid for both projects. The donations are part of the company’s overall contribution to Hardy County, where nearly one out of every three jobs is working directly for the company and dozens of local farms raise chickens to be processed at the plant.

There’s also a company housing program. For a weekly fee taken directly out of their paychecks, some employees live in housing in Moorefield and surrounding towns, like Petersburg. Pilgrim’s partners with the Potomac Valley Transit Authority to get employees to the factory.

This year, the company is building a 168-unit Moorefield apartment across the street from the town laundromat and a few hundred yards away from its factory. Over the past few months, construction workers have shaped lumber beams, glass panels and pickle-green plywood into a three-story complex.

The construction of Pilgrim’s new Moorefield apartment complex in February 2024.

(Photo by Roger May)

In a letter to state senators and delegates who represent Hardy County, Collins, the plant manager, said the apartments are designed to address the local affordable housing crisis, a problem throughout Eastern West Virginia.

“Much of our existing workforce is shuttled in from homes in the neighboring counties of Grant, Hampshire and Pendleton,” Collins wrote. “Having local, affordable housing options will help our employees and the employees of other local businesses secure a better work-life balance.”

Workman, the Hardy County Commission president, is glad the apartments are coming to an area that desperately needs more places to live. Two local school teachers he knows had to check surrounding counties to find adequate housing in their price ranges.

But he does worry about Hardy furthering its reliance on a single employer.

“Like the old coal company,” Workman said. “And that’s a concern, I mean, as you look at history.”

Living in company housing can be expensive. Mountain State Spotlight spoke with multiple immigrant families who lived in Pilgrim’s housing and found the rent can be far higher than similar units. Spotlight verified these costs by examining employees’ pay stubs to see how much money Pilgrim’s subtracted for rent.

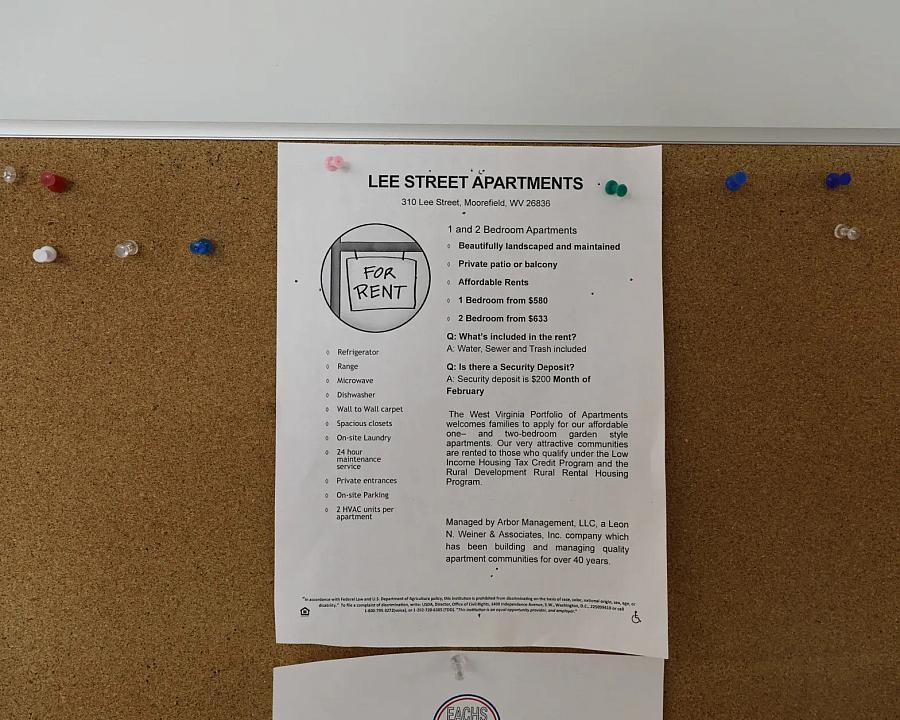

An advertisement for apartments in Moorefield. A 1-bedroom apartment is listed at $580 per month, and a 2-bedroom unit is listed at $633 per month.

(Photo by Roger May)

Two Haitian workers Mountain State Spotlight spoke with paid around $1,300 per month for a one-bedroom apartment before moving to a non-Pilgrim’s unit. In contrast, the 2024 fair market monthly rent for Hardy County units are $685 for one bedroom and $869 for two bedrooms, according to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

Pilgrim’s officials didn’t respond to questions about how the company set these prices and whether it expects to charge their employees similar rent for the new apartment units.

Melissa Judy stands in front of her black truck. Judy, a worker at the Moorefield Pilgrim’s Pride factory, has lived in West Virginia’s Potomac Highlands her whole life.

(Photo by Roger May)

Melissa Judy, a 53-year-old Pilgrim’s production employee, has lived in Eastern West Virginia her whole life. She said it’s mostly immigrant workers who live in company units, something that frustrates her and other white workers who struggle to find places to live.

“There’s no places to rent for us Americans,” said Judy, who lives in a camper van. “It upsets me.”

The disconnect between some immigrant and non-immigrant workers makes Susie Webster, a former plant worker who now works at the laundromat across from Pilgrim’s new apartment complex, think the chicken company is creating unnecessary tension between white and immigrant workers.

At the laundromat, Webster frequently helps newcomers wash their clothes and run the machines. While she doesn’t share a language with most, she believes many could use more support in Moorefield.

Susie Webster stands with her arms apart at the Moorefield Speed-Wash laundromat where she is an attendant. Webster used to work at the town’s chicken factory.

(Photo by Roger May)

“It’s almost like immigrants were brought here, dumped out like a piece of trash and not explained exactly what their resources are,” she said between folding clothes and exchanging a Haitian girl’s dollar bill for quarters.

“They deserve the same chance we got. Because they’re no different.”

Meeting Hardy County’s unique needs

As Assistant Superintendent of the Hardy County School District, Jennifer Strawderman knows Pilgrim’s creates a unique set of responsibilities for local government. Six percent of the kids in Hardy County schools were English language learners in the 2023-2024 school year — the highest percentage in a state where most districts don’t have a single student.

Jennifer Strawderman, the Hardy County School District assistant superintendent, sits at a conference table inside the district building.

(Photo by Roger May)

To meet the needs of immigrant students, Hardy County employs four English learner teachers — one for each Moorefield public school. Strawderman says she’s constantly impressed watching the four teach their students with limited resources.

And Pilgrim’s provides some help. In a district office conference room, she said the chicken company gives the Hardy County Schools about $7,500 a year, money that’s spent on a district-wide language interpretation subscription and an after-school English language program for students who can’t attend school in the morning.

“That’s going to allow them to graduate,” said Dennis Hill, a retired Hardy County teacher who taught English for speakers of other languages for more than a decade.

Dennis Hill sits at a conference table in the Hardy County School District building. Before retiring, Hill taught English to speakers of other languages in Moorefield.

(Photo by Roger May)

But Strawderman said the English learner student-to-teacher ratio can make connecting with kids challenging. In February, she said the high school English learner class had 54 students and one teacher.

And without aides in many classrooms, Strawderman said it’s difficult for the instructors to ensure that students learn because many of them join or leave the class in the middle of the year.

“It’s gotta be hardest on the kids,” she said.

It’s not just local government groups that are stretched thin. Through food banks, baby supply pantries and free summer school, Eastern Regional Family Resource Network tries to help Moorefield’s families meet their basic needs.

Like the school district, Pilgrim’s occasionally helps the nonprofit out. Joanna Kuhn, the organization’s director, said the chicken company donated $3,500 for an event to connect Hardy and Grant County residents with helpful resources.

But she said that’s a once-a-year donation, and her nonprofit still struggles to maintain other programs that immigrants rely on.

“Our baby bank has a very small budget of maybe $3,000 a year,” Kuhn said. “We’ve had to not give out as much.”

Ta-Yare Meade, another employee with the nonprofit, suggested Pilgrim’s could make $500 monthly donations.

“You’ve got to help us help your employees,” she said. “I don’t think that’s too unfair to ask for, to help us buy diapers and wipes and formula that the children of your employees need.”

When she worked for a rural Mississippi labor advocacy group in the early 2000s, Angela Stuesse also witnessed immigrant chicken factory worker families fight to survive and well-meaning groups struggle to help them.

Decades later and now an anthropology professor at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill, she said companies like Pilgrim’s undoubtedly have the money to address some of these issues.

“The problem isn’t having these new neighbors,” Stuesse said. “It’s the fact that somebody is profiting off of this movement of labor and humans and isn’t contributing what they should be to the well-being of the community.”

Love from a distance

A church on Moorefield’s Main Street.

(Photo by Roger May)

On a Sunday in May, Tatiana, the woman from Honduras, had $287.

“Two hundred at home,” she said. “And 87 in my pocket.”

She planned to use almost all of that to take care of her kids. Her younger child, her daughter, excels in school. Tatiana said she learned English in only a year, and she’s frequently bringing home praise and awards from the teacher.

When Tatiana has a bad day, her daughter will often cheer her up.

“Mom, you have suffered a lot,” the mother recalled her daughter saying. “But I’m going to give you everything. Because I know English, and I’m going to defend you. And when I grow up, I’m going to give you everything.”

Tatiana’s son is still with family in Honduras. It’s been nearly three years since she last saw him.

One of Tatiana’s last memories of Honduras is her son chasing after the bus she and her daughter boarded to start their journey.

“There’s no words for it,” Tatiana said. “Thinking that that may be the very last day you see him, knowing that you’re doing it to give him a better future.”

Like she has for the past three years, Tatiana plans to continue sending as much money to her family in Honduras as often as she can. She said there were times when all she had was $20, and she sent every dollar to feed her son.

It might be a while longer before they reunite. Tatiana is still looking to find a pathway to U.S. legal residency. She hopes it’ll open up jobs other than the one she has now — a labor intensive, low-paying job about an hour away from her home.

Despite all her disappointment, she continues to believe staying in the U.S. is the best way she can take care of her children.

“You have to separate yourself from those who love you for a plate of food,” she said.

A See ‘n Say toy has a variety of farm animal drawings. It plays Old MacDonald Had a Farm, and it belongs to the child of two Pilgrim’s Pride Moorefield immigrant workers.

(Photo by Roger May)

Lorena Ballester and Aliese Gingerich interpreted interviews with Spanish speakers for this story. Translations were produced by Gingerich (Spanish) and Christelle Georges-Louis (Haitian Creole).