What it’s like to work in child care, raise your kids and just get by in the Mon Valley

This story was produced as part of a larger project led by Rich Lord, a participant in the USC Center for Health Journalism's 2018 Data Fellowship.

Other stories in this series include:

Charges lodged in North Braddock arrest

Growing up through the cracks: The children at the center of North Braddock's storm

Where fighting poverty is a priority

Pittsburgh's neighborhood boosters face changing landscape

Current and former Rankin residents remember the past, envision the future

Rankin, Pennsylvania: Fighting 'the depressed mindset'

Growing Up Through the Cracks: Mapping Inequality in Allegheny County

A mother moves from McKeesport to Glassport to try to better her family’s chances

Growing up through the cracks: North Braddock: Treasures Amid Ruins

Saltlick: “They don’t know they’re poor.”

Pa. officials reverse course on local family support center funding

Study: An increasing number of Pa. kids living in high-poverty areas

By Kate Giammarise

On a slightly warmer than normal day in early January, Rebecca Brydges is on her lunch break, but she is still hard at work.

She is using the computer at the McKeesport Family Center to work on her resume.

Next door to an adult probation office, and amid the many vacant buildings in downtown McKeesport, the center looks a bit run-down from the outside.

But inside, it is teeming with bright colors and activity — the exuberance of young children and hustling staff.

The center aims to help families with young children by offering free services — everything from parenting advice and classes that promote healthy child development to helping with day-to-day needs.

Which brings Ms. Brydges here today to polish up her resume.

“I just need something that makes more money,” she explains.

She works at a nearby child care center, but she needs to earn enough money to support her own four kids, all under the age of 10.

Without a car, her transportation and job options are limited in McKeesport.

In Growing Up Through the Cracks, the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette is examining how concentrated child poverty harms kids, families and communities.

McKeesport, home to Ms. Brydges and her kids for about seven years, is one of several Allegheny County municipalities in which about half or more of the kids live in poverty. After living in Crawford Village, a public housing community, for about five years, they now live nearby.

While Ms. Brydges, 27, said she appreciates that living in McKeesport is cheaper than other places — “I could never afford to live in Pittsburgh,” she says — much of her paycheck and some child support are still covering just the basics.

She would like to be able to take her kids to places such as the Carnegie Science Center.

“Things like that, we can’t do, because my paycheck’s food. So, if I could make more money, I could do more things.”

Ms. Brydges, who has worked at several child care centers and has been a nanny, also is working on a Child Development Associate Credential.

She is trying to work her way out of the paradox faced by countless child care workers and parents — although child care is typically very costly and difficult for working parents to afford, child care workers often earn low wages and are barely scraping by.

For child care workers in the Pittsburgh area, the average hourly wage is $11.50, according to the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics, with an average annual wage of $23,090.

“It’s a huge challenge for the child care sector that, really parents and families can’t pay any more for child care, and yet the providers can’t make any less than they currently do,” said Lissa Geiger Shulman, director of public policy at Pittsburgh-based advocacy group Trying Together.

What makes it so costly?

Child care can’t be automated or enhanced by technology, and it requires many nurturing adults, often with state-mandated ratios, Ms. Geiger Shulman said.

“The biggest portion of a child care program’s budget is going to be those costs for salaries,” she said.

There are some subsidies for low-income parents, but not everyone who qualifies is able to receive them, and there is a waiting list. The subsidy rate also doesn’t cover the cost of care at many centers.

“To truly do what we think is right for children and families, the costs are large,” Ms. Geiger Shulman said. “That’s why a lot of other countries do have more significant public investments in their child care programs.”

McKeesport and Glassport: neighboring communities with different demographics

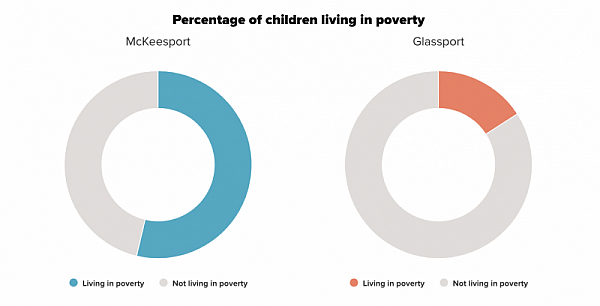

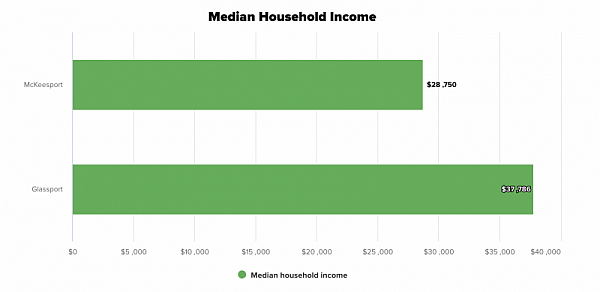

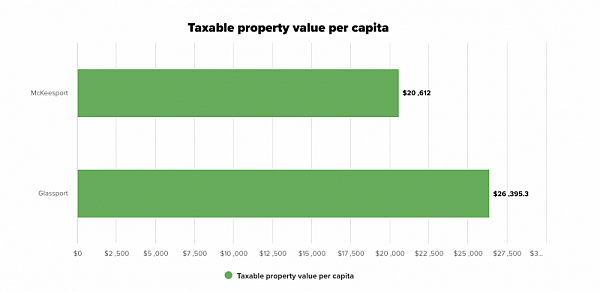

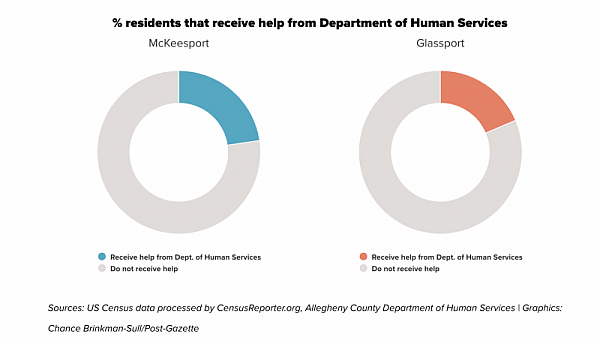

McKeesport and Glassport, neighboring Mon Valley communities, face many of the same challenges. But Glassport has a higher median household income and a much lower child poverty rate.

Starting Over

On a Saturday in March, Ms. Brydges’ children are playing in a living room without furniture in their new home in Glassport, a neighboring Mon Valley community.

Some problems in the McKeesport home, including peeling paint and mold, prompted the family to move. While Glassport isn’t a wealthy community, its child poverty is less than half of McKeesport’s. And it’s in the South Allegheny School District, which Ms. Brydges believes will better serve her son Jaxen, who is autistic. He will start kindergarten in the fall, at age 5.

But the move to better circumstances came with a bit of a setback.

She had paid a full month’s rent at her old apartment because she couldn’t move all her belongings at once and planned to move over two weekends. But her landlord in McKeesport threw out her living room furniture, her dresser and a set of bunk beds — items she had planned to retrieve before the end of the month.

“Now, I’m playing catch-up,” she said.

Still, she’s happy about the move.

“I think this is what’s best for my family,” she said.

A New Routine

fter completing her Child Development Associate Credential, Ms. Brydges in May started a schedule of working 20 hours a week and taking classes at Community College of Allegheny County.

She works in the morning, attends classes in the afternoon, takes online classes at night and on the weekends — all in addition to being a mom.

She doesn’t have a computer at home so she uses the McKeesport Family Center when she needs to do computer work.

Ms. Brydges’ ambitious goal is eventually to open her own child care center in Glassport.

“There’s no day cares here. And the schools won’t ship to the surrounding cities for day care … So my goal is to finish school, do my school schedule around [son Jaxen’s school] schedule, and when that’s done, I’m going to open up a center here in Glassport. Because I cannot be the only parent that has that struggle.”

On a recent Saturday in June, three of her four children are playing nearby. Sean, 10, is sleeping upstairs. Andre, 3, is playing upstairs in his room, Jaxen is pretending to be various super heroes on the back patio, and baby Karlee, 1, is alternately trying to keep up with her older brother and playing on a rideable Thomas the Tank Engine purchased at a bargain price from a thrift store.

“It’s a lot,” Ms. Brydges said of her schoolwork on top of working and parenting. “I have two papers due Monday morning. I can’t wait for nap time to sit down and try to get those done.”

Kate Giammarise: kgiammarise@post-gazette.com or 412-263-3909.

This story was produced with assistance from the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism‘s Data Fellowship.

[This article was originally published by the Post-Gazette.]