What's being done about the doctor shortage in Pennsylvania Coal Country?

Binghui Huang wrote this series as a project of the National Health Journalism Fellowship, a program of the University of Southern California's Annenberg School of Journalism.

Other stories in this series include:

Sick and struggling in Coal Country

Dentist Richard Vermillion talks to one of his patients, Annie Stoffey of Coaldale, at his Summit Hill office. As doctors and dentists retire, there aren't enough younger ones to take their place.

(Photo Credit: Rick Kintzel/The Morning Call)

Richard Vermillion is a dentist, and so is his wife. His father was a dentist, too. As was his grandfather. He even has an uncle who was a dentist.

All of them worked in Summit Hill, a Carbon County mining town of about 3,000 people.

But Vermillion’s two sons? They’re choosing different paths.

Vermillion and his wife, Jennifer, have a dental practice in the Ludlow Street office that Vermillion shared with his father. It’s just down the block from an earlier office Vermillion’s father and grandfather had. Many of his grandfather’s patients have had their molars checked by all three generations. In a county where dentists have become a rare breed, the practice is hugely important.

When Richard and Jennifer Vermillion — who are in their 40s — retire, Summit Hill will lose half its dental offices. Neighboring Coaldale and Lansford do not have any.

That’s a big difference from when Vermillion’s father, Louis, began practicing about 46 years ago, when there were more stores in Summit Hill and Lansford, as well as doctors.

“Every town had at least two dentists,” he said.

As medical professionals retire in Coal Country, there aren’t enough younger ones to take their places, leaving the area in desperate need of dentists, family physicians, mental health providers and other specialists. Fewer doctors mean people must travel farther for care, or go without.

Dr. Richard Vermillion talks to a patient at his office in Summit Hill. (Photo Credit: Rick Kintzel/The Morning Call)

In Carbon County, there’s one dentist for 2,360 residents, compared with the state average of almost two dentists for that many people. The shortage of primary care doctors is similar. The biggest difference is in mental health providers: Where Carbon has one for 2,190 people, Pennsylvania has four. Obstetrics is affected too. The county that once had two hospitals where women could give birth hasn’t had a maternity wing for the past decade.

The scene is changing, however, as the region’s largest health networks push into the Coal Region. In the last three years, St. Luke’s University Health Network acquired two hospitals in Carbon County, while two hospitals in Schuylkill County joined Lehigh Valley Health Network.

They are bringing needed specialists to an area where heart disease, cancer, respiratory ailments and other health conditions claim lives at a higher rate than the state average. But the home-grown family doctor that once was a staple in such towns is becoming extinct, as is the convenience of that neighborhood office.

Jeanne Stemler has lived through the changes, growing up in Nesquehoning, which had a coal mine where her father worked during World War II. She moved to Palmerton to attend the nursing school at the hospital. At 91 years old, she and her husband, Milton, 95, enjoy daily games of Scrabble and a vista of Blue Mountain from their home outside Palmerton.

Milton Stemler, 95, smiles as he grabs another letter while playing Scrabble with his wife Jeanne, 91, in their Lower Towamensing Township home. The couple play the game on a daily basis. (Photo Credit: Rick Kintzel/The Morning Call)

The setting was just what Milton needed as he recuperated last summer from a health scare, sitting outside on breezy day with a glass of white wine and a bowl of pistachios, which he ate at a leisurely pace.

St. Luke’s is new to their neighborhood, having acquired Palmerton Hospital more than a year ago and then moving many of its services to the former Gnaden Huetten Hospital in Lehighton, which St. Luke’s acquired at the same time.

St. Luke’s plans to consolidate the two hospitals into a new one in Franklin Township. The network has not decided how it will use the existing buildings, spokesman Sam Kennedy said.

In August, a St. Luke’s administrator said the network likely would convert the hospitals into other medical uses.

Losing the community hospital could be a blow to Palmerton, which has a large number of retirees.

For Jeanne Stemler, it would be like losing a dear friend. She has an affection for Palmerton Hospital, having worked there as a nurse and then serving as a trustee.

When she and Milton were raising their children, it was a vibrant health hub, she said, holding free clinics and charity drives in a community where people not only knew each other but the doctors who treated them.

A rendering of St. Luke's University Health Network's proposed 80-bed hospital near Route 209 in Carbon County that would consolidate its recently acquired hospitals in Palmerton and Lehighton. (Contributed photo)

The hospital is the subject of a scrapbook of photos and news clippings passed on to her from a former co-worker.

Flipping nostalgically through the pages, Stemler pointed to a physician who held free clinics for babies to get checkups and vaccines.

“Now that’s a doctor who cared,” she said.

The Stemlers have had good luck with doctors. The family physician who earned their trust over the decades is in his 70s and presumably nearing retirement. Then what?, Jeanne Stemler wonders.

Admissions have been down at the Carbon hospitals, partly because population is down in the county too, but also because patients are traveling to the Lehigh Valley, Reading or Scranton, where there are far more health care options and specialists. In 2017, before St. Luke’s took over, the majority of the beds at Palmerton and Gnaden Huetten were unused, state data show.

“Health care is like the Walmart of America,” Jeanne Stemler likes to say, quoting a doctor who once used that comparison. “We have to keep those beds filled. That’s what it’s all about.”

Palmerton’s struggles had been mounting for years, and the hospital survived by merging once before St. Luke’s came along.

Hospitals are expanding, merging and growing to become multibillion-dollar companies, and in the process, they swallow up or squeeze out smaller hospitals. In the Coal Region, there’s a bright side to health care consolidation. For example, when LVHN moved into Schuylkill County, it brought its cancer center to the region. And last year, it introduced cancer, cardiology and orthopedic specialists at its offices in Lehighton.

St. Luke’s, which has three federally designated Rural Health Clinics in Carbon and Schuylkill, will be adding services too, including a Rural Health Clinic in Lansford. The hospital networks provide treatment regardless of a person’s ability to pay.

Jeanne Stemler just hopes to have at least an urgent care center for emergencies where Palmerton Hospital is now. Arguably, Carbon County needs that more than some other places, considering that 21 percent of its population is age 65 or older — four percentage points higher than the state average.

Essential services such as urgent care and outpatient care usually remain in communities, even after large networks take over. But urgent care centers are not intended to replace primary care. That, perhaps, is where the Coal Region sees its biggest need.

Dr. Gregory Dobash, a St. Luke’s primary care doctor who has been practicing in Tamaqua for about six years, has seen many doctors leave the area without being replaced.

“We’ve had physicians retire, we’ve had physicians pass away, we’ve had one local physician commit suicide,” he said.

Dobash’s practice has expanded to offer such services as fluoride varnish application and counseling. Still, he said, the demand for specialists in the region is not being met.

Heart disease, diabetes and lung problems are common among his patients, he said. But so are mental health problems and drug addiction.

To address the doctor shortage, which is even more severe in truly remote areas of the country, the government started a program that offers permanent residency to immigrant doctors who practice in underserved rural areas.

That program allowed Dr. Raja Abbas, who is from Pakistan, to get a green card and work in Dubois, Clearfield County. He found that he liked practicing in a rural setting. From there, Abbas, who is a psychiatrist, established a practice in Palmerton in 2013, which he plans to move to Lehighton soon.

Dr. Raja Abbas, a psychiatrist, goes over data with his scribe, Angelina Catalano, at his Palmerton practice. (Photo Credit: Rick Kintzel/The Morning Call)

Abbas, 43, also has offices in the Lehigh Valley, but feels he is fulfilling a need for patients in the Coal Region.

“They’re more down-to-earth, open and appreciative,” he said. “And they need more care.”

Merely attracting doctors from abroad won’t bridge the chasm, said Dr. Joseph McGinley, a primary care doctor at St. Luke’s who helped launch the network’s rural residency program. Tackling the shortage will take a mix of strategies, including videoconferencing, through which doctors can treat patients remotely, and attracting doctors in training to learn at rural hospitals.

St. Luke’s started a three-year rural residency program last year with two students. It hopes to grow the program and to place those students in the more rural reaches of its coverage, including the Coal Region.

One of the reasons so few doctors want to go to rural regions is because most medical schools and hospital training programs are in cities, McGinley said. If doctors learn their craft in a rural area, the hope is that they’ll decide to settle there, bring their partner, have a family.

“They get accustomed to practicing in a hospital or community,” he said.

Medicaid not accepted

Large hospital networks are in a better position to counter one of the major drawbacks for doctors working in the Coal Region and other rural areas: the high number of patients on Medicare and Medicaid. Because the government reimburses at a lower rate than private insurance, it can be cost-prohibitive for doctors to have a lot of patients on medical assistance.

Richard Vermillion, the dentist, is among those who don’t accept Medicaid. He said he tried for a year but the costs and logistics didn’t work out.

So Carol Loggins, who lives about three miles from Vermillion’s office but is on Medicaid, had to drive 20 miles to Hazleton when her tooth started aching in 2017.

It took her six weeks to get an appointment, only to have the dentist refer her to an oral surgeon in Stroudsburg, which is more than an hour from her home. But when she got there, the office was closed for an emergency.

“I’m like, are you kidding me? I drove an hour and a half and they’re closed?” she said.

More than a year later, her tooth has not been extracted.

Long drives aren’t just inconvenient, they cut sharply into Loggins’ tight budget. She receives about $800 a month in disability and her boyfriend pitches in with shifts here and there at a chicken farm.

Loggins moved from Philadelphia to Coaldale in 2013 after a home invasion. She was shocked to find that life in the Schuylkill County borough was in some ways more difficult than life in Philadelphia. In the city, travel wasn’t the issue that it is in Coaldale.

She said she stays for her son, a middle schooler in the Panther Valley School District.

“Do I think it’s a better school district? Well, I can give it to you this way,” she said. “I think it could be a little better up here, but it's a whole lot better than in the cities.”

Maternity goes away

Alicia Kachmar gave birth to her daughter Willow at Gnaden Huetten Hospital on June 27, 2009, making the baby one of the last born at a Carbon County hospital before the unit closed.

“They took pictures of me and Willow,” Kachmar said. “I had to sign this book and everything because we were the last leaving the floor.”

Alicia Kachmar of Lansford takes a puff from her cigarette outside of Coal Miners Bar & Grill in Lansford. (Photo Credit: Rick Kintzel/The Morning Call)

Carbon County’s other hospital, Palmerton, closed its maternity ward a few years earlier — turning it into an older adult behavioral health center as population trends shifted.

Blue Mountain Health System, which owned both, lost about $820,000 on OB/GYN services the year before Gnaden Huetten closed its maternity wing.

Kachmar had her two other children — Meadow and Andrew — at St. Luke’s- Allentown, about an hour from her home in Lansford. She said Meadow was almost born in the car — even though Kachmar’s mother, who was driving, sped the whole way. At that point, Kachmar was accustomed to the ride, having to go routinely to Allentown not just for regular obstetrics visits but to see specialists because the baby had a hole in her heart.

Maternity wings in rural counties are shutting down across America. In 2004, 54 percent of rural counties had maternity wings. By 2014, only 46 percent did, according to a study by the University of Minnesota’s Rural Health Research Center.

As is the case in Carbon, declining population, low medical assistance reimbursement rates and trouble attracting doctors and nurses are among the reasons for maternity wing closures, said Carrie Henning-Smith, a professor at the University of Minnesota who co-authored the study.

The closures could mean more women giving birth at home, in emergency rooms or on the side of the road, Henning-Smith said.

Maternal mortality rates in rural areas are more than 60 percent higher than in urban areas, according to Scientific American’s analysis of 2015 data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Rural regions also have higher rates of infant mortality, premature births and low birth weight.

“There’s not one cause. There’s not one villain, which makes this a challenging and complicated problem,” Henning-Smith said. “But also that means there could be a variety of solutions.”

Along with what the local hospitals are doing to attract more physicians to rural areas, Henning-Smith suggested training family members and emergency responders to deliver babies in far-flung communities.

For the last decade, new mothers have been trekking beyond Carbon County for labor and delivery. For them, the local maternity wing is a thing of the past.

Kachmar is proud to be part of the lore. But maternity wings have no place in her future — she had her tubes tied after her third child.

A hole in mental health care

A history of Travis Litts’ mental illness is etched on his arm, faint lines where he cut himself to find relief from painful emotions.

He has been on and off of anti-anxiety, antidepressant and antipsychotic drugs: Effexor, lorazepam, gabapentin, to name a few.

Travis Litts stands in his bedroom next to a picture of himself kissing his son. Litts lost custody of his son and hit his former girlfriend when he was high in an Allentown hospital nearly two years ago. (Photo Credit: Rick Kintzel/The Morning Call)

The side effects of these drugs can be intense, and withdrawal is even worse, said Litts, who is 32 and shares an apartment with Kachmar in Lansford.

One time when he couldn’t afford a refill of Effexor and ran out, he started thinking about suicide and eventually went to an emergency room.

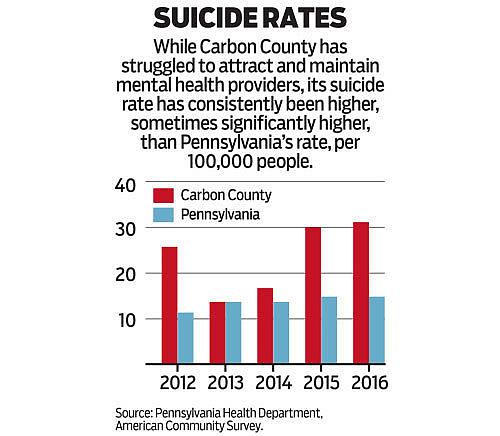

In Carbon County, suicide is the leading cause of death among people 25 to 44 years old, according to St. Luke’s University Health Network’s community health needs assessment. In Schuylkill County, it’s the second-leading cause among that age group.

Suicides are higher in rural areas than in metropolitan counties, according to the state Health Department. In Carbon County, where the population is about 64,000, the suicide rate is about 31 deaths for every 100,000 residents, compared with the state’s rate of about 15.

Litts said he’s been in several hospital psychiatric wards and been put into restraints enough times that he can recite how it works.

“They put your hands behind your back and buckle you down, and then this leg and this leg and they buckle them down,” he said. “After one hour they unbuckle this arm. After another hour they unbuckle this leg. And if you’re good they’ll unbuckle the other leg.”

The psychiatric ward has helped him in a crisis but its effects are short-lived.

He needs someone to talk him through his anxiety and depression, but he hasn’t had a regular therapist in years.

(Credit: Eugene Tauber and Jesse Musto/The Morning Call)

When he was in his 20s, Litts lived in Allentown and went to therapy every week, something he said helped him stay off drugs for a few years, and out of the emergency room.

Mental health problems often prompt people to seek help in the emergency room because they don’t know where else to go, said Abbas, the Palmerton psychiatrist.

In 2017, Reading Health opened a psychiatric emergency department because so many people were going to the hospital for mental health crises.

In Palmerton, Abbas sees about 20 patients a day, spending 15 minutes to more than an hour with them, depending on their needs.

One of his patients, Keith Enlund, is recovering from addiction, and like Litts has been through treatment and jail on his circuitous route to sobriety. Enlund, 33, of Albrightsville, credits Abbas with helping him sort through his anxiety and depression.

Keith Enlund of Albrightsville before his addiction recovery support group meeting at a church in Lehighton. (Photo Credit: Rick Kintzel/The Morning Call)

He said Abbas gives him time to talk through his problems. But more importantly, he gave Enlund another chance after he relapsed.

“I sent an email saying, ‘Please give me another chance, I’m going to die out here and I don’t want to,’ ” he said. “And he accepted me back there at [the clinic] and kind of saved my life.”

Abbas said he is bucking a trend, where doctors see 60 or more patients a day, spending just enough time with each to make sure the medication they prescribed isn’t causing bad side effects.

“It’s not just the access issue,” he said. “It’s what are you doing with a patient who shows up?”

Unlike many mental health providers, Abbas’ office takes patients with medical assistance and those who are uninsured, which cuts into his profits.

“But it works out for us in the sense that it all depends on how much money are you wanting to make,” he said. “Are you giving them quality or are you just seeing them because you want to see as many as possible?”

Like Abbas, some doctors are drawn to the Coal Region because they want to help people who desperately need it.

And others, like Louis and Richard Vermillion, are in the region because their roots are there.

Louis Vermillion, 70, served as president of the Panther Valley School Board, volunteered at his church and in his community.

His work was made more meaningful because of those connections.

“It’s a small town,” he said. “We take care of friends and family.”

[This story was originally published by The Morning Call.]