When Home is Not a Safe Haven

This story is part of a series produced by Pooja Garg, with support from the USC Center for Health Journalism's Domestic Violence Impact Fund.

Other stories by Pooja Garg:

Empowerment Project: Storytelling with Sakhi

Empowerment Project: Storytelling with Sakhi: Bent But Not Broken: Uma's Story

Khabar

While the South Asian community riding on the wave of model minority myth applauds its women achievers, it refuses to acknowledge the dark underbelly of abuse that takes place under the garb of close family ties. The current pandemic has brought into sharp focus what we have come to know as the shadow pandemic: the staggering rise of domestic violence incidents across the world.

But even before the coronavirus made us hunker down in our homes, the situation has been dismal for women in our community. Khabar explores the cultural context that makes this possible, along with the vulnerabilities that come with the challenges thrown in by the immigration laws and the legal system.

In an effort to reveal the human face of abuse beyond just the numbers, on the Khabar website, we bring true life stories of domestic violence survivors who made it to safety. The ones who come out are a very small percentage of the ones who go through abuse. As they share their intimate experiences in their own words, we hope that this inspires others to make a choice towards living without fear.

Khabar also conducted a survey to see how well we understand abuse as a community. The results are below in this article.

- Names have been changed to protect the identity of the survivors.

- Content Warning/Trigger Warning: domestic violence, violent imagery, language, abandonment, mental and physical health, depression, anxiety, trauma.

In an Atlanta suburb, Uma had just come back from her chemotherapy session when she heard her husband shout at her. As she turned to face him, she received a sudden blow on her chin. As Uma stood scared and pressed against the cold wall, her body was aching right down to the bones. She had been diagnosed with cancer a few months ago. But it didn’t stop her husband from accusing her of being lazy and not taking care of chores. Her pain was just a bahaana, an excuse, he said. Uma’s mother, who had come from India to help her daughter during her treatment, tried to intervene. She was pushed aside. When Uma tried to feed her kids, he threatened to hurt her if she came near them.

A successful IT professional, a dutiful wife, a loving mother, an understanding daughter, a cancer patient, Uma had also become a domestic violence victim.

Uma is one of the 40 percent of all Indian American women

Uma’s plight is also the plight of one-third of all Indian women and one-fourth of all women in the U.S. With one-tenth of men facing domestic violence or intimate partner violence (IPV) as per the U.S. Department of Justice, it is a myth that men can’t be victims of abuse. However, domestic violence is largely a gendered issue with numbers for abused women being significantly larger and with patriarchal conditioning that places power and control in the hands of men. According to data from India’s National Family Health Survey from the year 2015-16, more than 30 percent of ever-married Indian women aged between 15 and 49 years experienced spousal violence.

These numbers are the same or higher for the Indian community residing in the U.S. According to community-based surveys conducted by Anita Raj of the University of Wyoming in 2002 and Neely Mahapatra of the University of California in 2012, 40 percent of South Asian women in U.S. experience intimate partner violence. This data could well be applied to Indian American community who make up 80 percent of all South Asians in the U.S, as per the 2018 American Community Survey.

The fact that almost every state in the U.S. has one or more nonprofits working to support South Asian victims of violence tells its own story.

The shadow pandemic

Aparna Bhattacharyya, Executive Director, Raksha.

Helplines of these nonprofits buzzed with an upsurge in distress calls and shelters overflowed as Covid- 19 became responsible for unleashing not just the medical pandemic, but also what we have come to know as the shadow pandemic: the rise of domestic violence as victims stayed trapped with their abusers inside homes. Daya, a nonprofit serving South Asian victims of violence in Houston, saw a sharp increase of 44 percent in their distress calls. In India, we saw a 48 percent increase as reported by the National Commission of Women. According to UN Women, most countries saw a spike of more than 30 percent in reported cases. However, even these increased numbers seen around the world are not reflective of the reality on the ground, according to Anjali Guntur, Advocacy Services Manager at Raksha, a similar nonprofit in Georgia. “Many survivors are not able to reach out due to their abusers being home and lack of opportunities to reach out for help,” she says.

“It takes an inordinate amount of resiliency for South Asian immigrant women survivors of domestic violence to seek outside help,” say Neely Mahapatra of the University of California and Abha Rai of the University of Georgia in their research on domestic violence.

The paradox of achiever women and abused women

Even as Indian American community thrives on the model minority myth and celebrates its women achievers, we continue to be deeply rooted in patriarchal values. We are seen as a family-oriented community retaining strong cultural values. But our numbers on domestic violence show that even as we have moved away from India to improved life circumstances, at home nothing much has changed for our women. And if one thought that the numbers above were acute, data shows that reported cases are only a fraction of the reality. Most often, women don’t report. Instead, they rationalize and internalize abuse by blaming themselves for not living up to the expectations of a good wife. “The most important factor in these women’s lives seems to be the childhood indoctrination into the ideals of good wife and mother that include the sacrifice of personal freedom and autonomy. Furthermore, they feel responsible for the reputation of their families in India,” say researchers Shamita Das Dasgupta of the Rutgers University and Sujata Warrier of the New York State Office for the Prevention of Domestic Violence. This is further exacerbated by how community reacts when women get divorced. Many survivors feel that their friends disappear and they no longer get invited to social events when they are separated or get divorced, according to Aparna Bhattacharyya, Executive Director of Raksha.

Log kya kahenge? What would people say?

Rachna Khare, Executive Director, Daya.

The reputation of her family was very much on Uma’s mind when she finally had to make the 911 call that she had been avoiding for the longest time. “In all the years that I shared my experience with my family, they told me to bear it. My parents said that every relationship has problems and I need to make it work. Even my Indian friends and neighbors here in the U.S. told me to not do anything that would set my husband off.” When she called the police, they moved away from her. Even her kids were no longer invited to the playgroups. “We talk about community but where is the community support when we need it?” wonders Uma.

Swati Bakre, a Chicago-based counselor who works with trauma victims, says, “Isolation can be very traumatic. It is very important that we support the victims of violence as a community.”

For Jaya, an IT professional who came to the U.S. with her husband and then suffered spousal violence, her family’s support made all the difference when she moved away with her kids from Atlanta to another part of the U.S. to be with them. “It gave me a ground to stand on. I could start rebuilding myself,” she says, even though she didn’t stay with them for long. “Women who received support from their family have found it easier to overcome the stigma and get away from the abuser,” says researcher Tueta Peja of the Loyola University.

Sarita, another woman we spoke to, was choked by her husband and lost consciousness. When she regained consciousness, she was in the hospital. Scared for her life, she told the truth when authorities asked her. When her husband was apprehended, her mother-in-law called her and blamed her for putting her son in jeopardy and for bringing shame to the family. “I had come close to dying, and yet nobody thought of me, of what he had done to me,” says Sarita. Under family pressure and promises from her husband to do better, Sarita withdrew her complaint.

Intergenerational trauma

In insisting for Sarita to excuse her son and accept her situation, her mother-in-law was following the same pattern that generations of women had continued before her: accepting abuse as part of life for the sake of keeping the family together. For a culture that prides itself on close community ties, the same bonds turn into bondage for women who are expected to keep quiet and carry on.

For Uma too, her final break with her husband’s side of the family came when she called 911 as he hit her after her chemotherapy session. “My mother-in-law accused me of being a terrible wife; that I was trying to destroy his career. Nobody said anything when he hurt me even though I supported him throughout for his studies and visa,” says Uma.

Anjali Guntur, Advocacy Services Manager, Raksha.

Just like Sarita’s mother-in-law, Uma’s mother-in-law too said something she believed: that good wives do not bring shame to their husbands. Maintaining the status quo is the norm. She had, in fact, in a rare moment of openness with Uma, admitted to facing abuse at the hands of her husband. “My mother-in-law faced abuse at the hands of my father-in-law. I also could see it from the first day of my marriage,” says Uma.

Uma’s husband brought the same power and control dynamics in his marriage that he had witnessed in his parent’s relationship. “I told him that he was being abusive, but he dismissed it. He didn’t think of what he was doing to me as abuse,” says Uma.

According to researchers Aparna Mukherjee and Sulabha Parasuraman of the International Institute for Population Sciences, “Witnessing violence between one’s parents while growing up is an important risk factor for the perpetration of partner violence in adulthood. Women become more acceptable to violence. For men, the risk of perpetrating spousal violence increases. Men usually tend to take up the stereotyped gender roles of domination and control, whereas women grow up to follow the path of submission, dependence and respect for the authority throughout her life.” This has set a pattern that continues through generations.

Have we normalized abuse?

“Domestic violence is physical but can also be emotional, verbal, psychological, sexual or financial. In our communities, survivors must navigate the additional barriers of language access, in-law abuse, immigration abuse and strong cultural taboos,” says Rachna Khare, Executive Director of Daya, a Houston-based nonprofit for South Asian victims of violence.

Domestic abuse has become so normalized in our community that according to India’s 2016 National Family Health Survey, more than 50 percent of Indian women believe that it is reasonable for a husband to beat his wife, and more than 40 percent of men agree with it. The reasons could be: if she doesn’t cook properly, neglects the house or children, argues, shows any disrespect towards in-laws, goes out without informing, refuses to have sex, or is suspected of being unfaithful.

If we thought that this scenario is true of rural India, we can think again. Because the same survey shows that domestic violence numbers are not very different for these two demographics—29 percent for rural vs 23 percent for urban. So even when our educated, professional and financially independent women from towns and cities of India come to U.S., they are unable to shed the cultural conditioning of subservience that they have inherited.

Women empowerment and cultural conditioning

Sirpa Vigdorov, Chairperson of Cobb County Domestic Violence Taskforce and Head of Victim Witness Unit, Cobb Judicial Circuit.

Now a successful IT director, Uma defies the image most of us have of a domestic violence victim. She came to the U.S. for a master’s in computer science, had her own visa. When her husband lost her job, she supported him when he decided to study further and added him to her visa.

Jaya, yet another woman who suffered spousal violence, was working in the IT industry in India when she came to the U.S. with her husband. She was quickly absorbed in the workforce here and rose up the corporate ladder by dint of her hard work.

And yet, the cultural conditioning made Uma and Jaya accept their husbands’ role as the decision-maker with no room for their choice and autonomy. “If I bought even a plant, it created havoc at home,” says Uma. Once, when Uma enrolled her kids in a hobby class without ‘permission’ from her husband, she returned home to abuse. Jaya echoes, “I never knew what would cause him to get angry and hurt me. I was walking on eggshells around him.”

According to Dasgupta, “Even for women working as professionals, economic independence does not seem to provide them with a sense of empowerment.”

Financial dependency and immigration status: a vulnerable spot for victims

In the absence of economic independence, the dependence on the partner is further pronounced leaving women even more vulnerable to abuse.

Sahar Naqvi from Daya says, “98 percent of the victims of domestic violence have faced financial abuse. It is the keystone to the cycle of abuse.” Shweta Saji from Sakhi for South Asian Women, a New Jersey-based nonprofit, explains, “It could be stopping the survivors’ access to resources and money, stopping them from seeking employment or continuing education. The motive is to make the survivor vulnerable and dependent upon the abuser, so it is hard for them to break the cycle of abuse.”

Adding to their vulnerability is their dependence on abusers to stay in the country based on their visa status. These women have long faced the threat of losing their immigration status if they walked out of their marriage.

For Sarita, who told the truth about her situation to the authorities in the hospital and then gave in to her mother-in-law’s appeals to withdraw her complaint, this became a harsh reality—as soon as that process was over, instead of coming back home, her husband fled the state with his mother. He then divorced her without her knowledge. Sarita now faces a marital dilemma—she is married as per Indian law and divorced in the U.S. With her immigration status, which was tied to her husband’s visa, lying in limbo, she was forced to move back to India.

Sarita is one of many Indian women who are stranded by their husbands in the U.S. or taken to India with the intention of not bringing them back. Strategically stripped of access to legal forums, these victims of transnational abandonment lose foothold in both the countries—unable to pursue life that they had started in the U.S., unwilling to stay in India for the stigma they and their families face. Often, in one heartbreaking step, these victims lose custody of their children to the abusive partner. “What I went through makes me thankful that it got over before I had children. I can’t imagine what I would have done if I had lost them,” says Sarita.

“For women trapped in abusive marriages, securing their stay in the U.S. can be challenging because maintaining legal status sometimes requires cooperation from the abusive spouse. This forces many women to choose between two equally disempowering options: remaining in a violent situation or losing their immigration status,” highlights a letter addressed to the White House Advisor on Violence Against Women by the South Asian Americans Leading Together (SAALT).

Many are here on H4 dependent visas as spouses of H1B visa holders which make up a huge chunk of Indian immigrants in the country. Indians also get a large percentage of L1 visas—around 30 percent, as per the Migration Policy Institute. Their spouses on L2 visas are similarly dependent.

Some avenues for relief

With divorce in the U.S., Sarita’s immigration status changed, and her work visa expired. “I married an Indian and got married in India. My divorce should also be under Indian laws,” says Sarita.

Kamla, who came to the U.S. after an arranged marriage, found herself lost when faced with abuse. “I was asked to hand over my passport, my jewelry, all the money I had. He punched me or slapped me or kicked me,” says she.

For women like Sarita and Kamla, who find themselves abused or deserted, the Indian consulates offer some initial support and assistance by getting in touch with advocacy and legal groups here. National Commission for Women in India has set up a 24-hours helpline.

Says Sirpa Vigdorov, Chairperson of Cobb County Domestic Violence Taskforce and Head of Victim Witness Unit, Cobb Judicial Circuit, “We offer help and support to anyone being victimized, irrespective of their nationality or immigration status.”

When the Trump administration had proposed to revoke permission to work for spouses of H1B visa holders, 90 percent of the affected H4 Employment Authorization Document (EAD) holders were Indians with 93 percent of them being women, according to USCIS. With the Biden administration permitting them to work, it has provided relief to these women, many of whom were stuck in the domestic abuse cycle.

In fact, under the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA), now women on H4 visas facing domestic violence can decide to walk out of their marriage without worrying about the immediate loss of immigration status. Divorce no longer affects H4 visa holders’ rights to apply for work authorization for up to two years. It can also be renewed after that period. Says Nisha Karnani, Georgia-based immigration attorney with Antonini and Cohen, “The new work authorization is a tool of empowerment for the abused H4 visa holders to be independent of their abusive partners.”

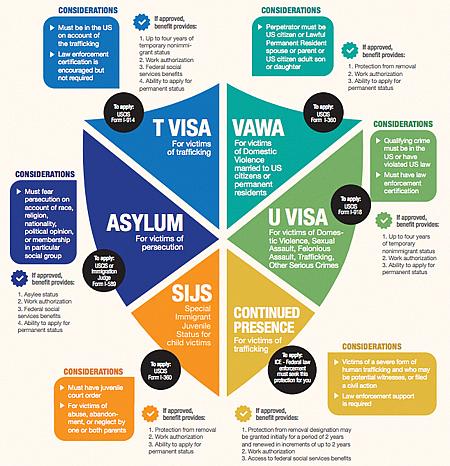

Source: National Resource Center on Domestic Violence.

Explains Aparna Bhattacharya, Executive Director of Raksha, who was one of the driving forces in mobilizing the USCIS to implement this policy, “This relief of H4 EAD for abused women is different from the general H4 EAD. The EAD for Abused Spouses of H1B’s was originally passed under VAWA 2005. Unfortunately, many individuals had forgotten about it since it impacted only certain non-immigrant visas. At the time, all of the focus was on getting regulations for the U visa. Immigration lawyers would not believe that this existed, and I would send them information to remind them. Under the Obama administration with leadership of colleagues like Manar Waheed, Deputy Policy Director for Immigration at the White House Domestic Council and Amanda Baran, Principal Director of Immigration Policy with Department of Homeland Security, we were able to bring more attention to getting the regulations out. The abused EAD was passed into law in 2005 but regulations needed to apply did not came out until February 14, 2017.”

Under the modifications, they can also apply for a non-immigrant U visa which is granted to those who have been subjected to mental or physical abuse. In the process, one can request for a waiver which allows for the paperwork to be signed without the signature of the abusive spouse. This inclusion of H4 visa holders is a modification from when VAWA allowed for spouses and children of only citizens and permanent citizens to self-petition to obtain lawful residency.

With over 75 percent South Asians in the U.S. born abroad, as per data by SAALT, the community possesses a range of immigration statuses, including unauthorized. In fact, the number of undocumented Indian Americans has seen a 140 percent rise over the past decade, according to a 2018 report by the Pew Research Center. Women from this section are especially vulnerable to abuse.

Isolation and cultural barriers present extra challenges. “Survivors find racism and discrimination in the system. They are mistrustful of the police and legal system. There is need for culturally informed services and community education to generate awareness about available services such as domestic violence ser-vices, legal assistance and network of South Asian women’s organizations,” say r searchers Bushra Sabri and Anuja Shah of the John Hopkins University with Shreya Surendramal Bhandari of the Wright State University,

The road ahead

Even as we negotiate through the chaos of legal system and the immigration laws for disenfranchised victims of domestic violence, finally it is about two people in an unequal relationship of power and control. It is at this nodal level that our community needs to restore equality between genders. Kamla Bhasin, the eminent Indian feminist who also had faced domestic violence, passed away recently. Said she, “My body is my biology. But my gender is socially constructed. We are taught gendering by society—which roles should the daughter play versus the son. Nature doesn’t say who is superior, patriarchy does. We are born humans, but are put in boxes of defined gender roles.” As a community, we need to dismantle these boxes.

This feature is part of Empowerment Project undertaken by Pooja Garg for Khabar magazine in collaboration with Raksha and The Woman Inc. It is supported by USC Fellowship for Domestic Violence Impact Reporting.

The write-up published here is an abridged version of the complete article. For the complete article and listing of citations, read on Khabar website.

Pooja Garg is City Editor & Community Engagement Editor of Khabar magazine. Member of Cobb County Domestic Taskforce, she is Founder Chief Editor of The Woman Inc., an advocacy and literary nonprofit magazine. To connect with her: linktr.ee/poojagarg .

Art: Alka Writes is a California-based poet, artist and women's rights advocate. Her work has been reproduced here with permission from The Woman Inc. where it had previously been published as part of a series.

In our endeavor to support, Khabar has put together a short information kit to help us understand more about domestic violence, the cycle of abuse, what makes some of us stay in abusive relationships, some helpful resources in case we face an abusive situation, and how we can help someone facing abuse.

Sources: The United Nations, National Coalition Against Domestic Violence, National Violence Domestic Hotline, Office on Women’s Health, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, and U.S. Citizenship & Immigration Services.

What Is Domestic Abuse?

Domestic abuse, also called domestic violence or intimate partner violence, can be defined as a pattern of behavior in any relationship that is used to gain or maintain power and control over an intimate partner.

Abuse is physical, sexual, emotional, economic or psychological actions or threats of actions that influence another person. This includes any behaviors that frighten, intimidate, terrorize, manipulate, hurt, humiliate, blame, injure or wound someone. Incidents are rarely isolated, and usually escalate in frequency and severity. Domestic abuse may culminate in serious physical injury or death.

Domestic abuse is typically manifested as a pattern of abusive behavior toward an intimate partner in a dating or family relationship, where the abuser exerts power and control over the victim.

Domestic abuse can happen to anyone of any race, age, sexual orientation, religion, class or gender. Domestic violence affects people of all socioeconomic backgrounds and education levels.

Domestic abuse can occur within a range of relationships including couples who are married, living together or dating. Victims of domestic abuse may also include a child or other relative, or any other household member.

Are You Being Abused?

Answer the following questions to think about how you are being treated and how you treat your partner.

Does your partner:

- Embarrass or make fun of you in front of your friends or family?

- Put down your accomplishments?

- Make you feel like you are unable to make decisions?

- Use intimidation or threats to gain compliance?

- Tell you that you are nothing without them?

- Treat you roughly—grab, push, pinch, shove or hit you?

- Call you several times a night or show up to make sure you are where you said you would be?

- Use drugs or alcohol as an excuse for saying hurtful things or abusing you?

- Blame you for how they feel or act?

- Pressure you sexually for things you aren’t ready for?

- Make you feel like there is “no way out” of the relationship?

- Prevent you from doing things you want—like spending time with friends or family?

- Try to keep you from leaving after a fight or leave you somewhere after a fight to “teach you a lesson”?

Do you:

- Sometimes feel scared of how your partner may behave?

- Constantly make excuses to other people for your partner’s behavior?

- Believe that you can help your partner change if only you changed something about yourself?

- Try not to do anything that would cause conflict or make your partner angry?

- Always do what your partner wants you to do instead of what you want?

- Stay with your partner because you are afraid of what your partner would do if you broke up?

Always remember that NO ONE deserves to be abused. The abuse is not your fault. You are not alone. Here is a toolkit to understand if you are experiencing abuse:

https://www.domesticshelters.org/common-questions/am-i-experiencing-abuse

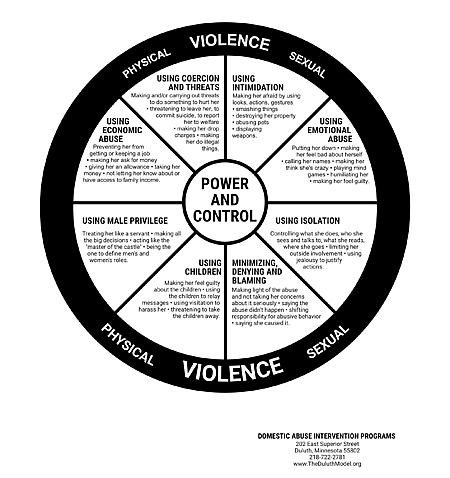

Power and Control Wheel

(Developed by Domestic Abuse Intervention Project, Duluth, MN)

Source: theduluthproject.org

The Power & Control wheel is helpful in understanding the overall pattern of abusive and violent behaviors, which are used by an abuser to establish and maintain control over his/her partner or any other victim in the household. Physical and sexual assaults, or threats to commit them, are the most apparent forms of domestic abuse and violence. These may be accompanied by an array of these other types of abuse which are less easily identified, yet firmly establish a pattern of intimidation and control in the relationship.

Can anyone be a victim of domestic violence?

Yes. There is NO “typical victim.” Victims of domestic violence come from all walks of life, varying age groups, all backgrounds, all communities, all education levels, all economic levels, all cultures, all ethnicities, all religions, all abilities, and all lifestyles.

Victims of domestic violence do not bring violence upon themselves, they do not always lack self-confidence, nor are they as abusive as the abuser.

Can anyone be an abuser?

Yes. They come from all groups, all cultures, all religions, all economic levels, and all backgrounds. They can be your neighbor, your leader, your friend, your child’s teacher, a relative, a coworker—anyone. It is important to note that the majority of abusers are only violent with their current or past intimate partners. One study found that 90 percent of abusers do not have criminal records and abusers are generally law-abiding outside the home.

While there is no one typical, detectable personality of an abuser, they do often display common characteristics. An abuser often denies the existence or minimizes the seriousness of the violence and its effect on the victim and other family members. An abuser objectifies the victim and often sees them as their property or sexual object. An abuser has low self-esteem and feels powerless and ineffective in the world. He or she may appear successful, but internally, they feel inadequate. An abuser externalizes the causes of their behavior. They blame their violence on circumstances such as stress, their partner’s behavior, a “bad day,” on alcohol, drugs, or other factors. An abuser may be pleasant and charming between periods of violence and is often seen as a “nice person” to others outside the relationship.

Can I find out at the beginning of a relationship if a person is abusive?

Source:domesticviolence.org

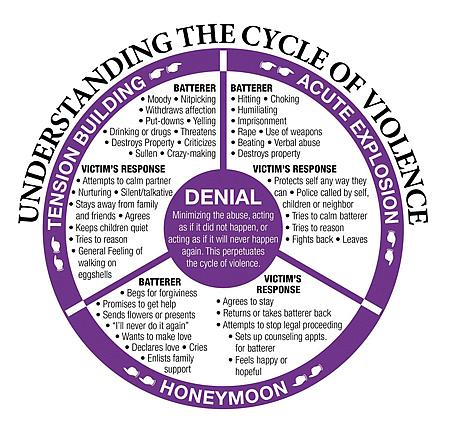

It is not always easy to determine in the early stages of a relationship if one person will become abusive. Domestic violence intensifies over time. Abusers may often seem wonderful and perfect initially, but gradually become more aggressive and controlling as the relationship continues.

Abuse may begin with behaviors that may easily be dismissed or downplayed such as name-calling, threats, possessiveness, or distrust. Abusers may apologize profusely for their actions or try to convince the person they are abusing that they do these things out of love or care. However, violence and control always intensify over time with an abuser, despite the apologies. What may start out as something that was first believed to be harmless (e.g., wanting the victim to spend all their time only with them because they love them so much) escalates into extreme control and abuse (e.g., threatening to kill or hurt the victim or others if they speak to family, friends, etc.).

Do victims choose to stay in abusive relationships?

Unfair blame is frequently put upon the victim of abuse because of assumptions that victims choose to stay in abusive relationships. A victim’s reasons for staying with their abusers are extremely complex and, in most cases, are based on the reality that their abuser will follow through with the threats they have used to keep them trapped.

Research says that most victims who finally leave try at least seven times before they succeed.

When it is a viable option, it is best for victims to do what they can to escape their abusers. However, this is not the case in all situations. Domestic violence does not always end when the victim escapes the abuser, tries to terminate the relationship, and/or seeks help. Often, it intensifies because the abuser feels a loss of control over the victim.

Bringing an end to abuse is not a matter of the victim choosing to leave; it is a matter of the victim being able to safely escape their abuser, or the abuser choosing to stop the abuse, or law enforcement and courts holding the abuser accountable for the abuse they inflict.

Source: Atlanta Legal Aid

How can I support someone facing abuse?

Watching someone endure an abusive situation can be difficult under any circumstances, and it’s not always clear how best to respond. Your instinct may be to “save them” from the relationship, but abuse is never that simple. There are many ways that abuse appears and there are many reasons why people stay in abusive situations.

Understanding how power and control operate in the context of abuse and how to shift power back to those affected by domestic violence are some of the most important ways to support survivors in your life.

Emotional Support

The experience of surviving relationship abuse is traumatic, and people in any stage of an abusive relationship should be able to depend on others for support as they process complex emotions and navigate the next steps.

You can provide essential emotional support by:

- Acknowledging that their situation is difficult, scary, and brave of them to regain control from.

- Not judging their decisions and refusing to criticize them or guilt them over a choice they make.

- Remembering that you cannot “rescue them,” and that decisions about their lives are up to them to make.

- Not speaking poorly of the abusive partner.

- Helping them create a safety plan.

- Continuing to be supportive of them if they do end the relationship and are understandably lonely, upset, or return to their abusive partner.

- Offering to go with them to any service provider or legal setting for moral support.

Material Support

Depending on the situation, a survivor may be financially dependent on an abusive partner or otherwise lack access to material resources. One of the most immediate ways you can support someone experiencing relationship abuse is by helping them with their material needs.

- Help them identify a support network to assist with physical needs like housing, food, healthcare, and mobility as applicable.

- Help them by storing important documents or a “to-go bag” in case of an emergency situation.

- Encourage them to participate in activities outside of their relationship with friends and family, and be there to support them in such a capacity.

- Encourage them to talk to people who can provide further help and guidance, like thehotline.org or teen and young adult project such as loveisrespect.org. (More resources follow in the article.)

- If they give you permission, help document instances of domestic violence in their life, including pictures of injuries, exact transcripts of interactions, and notes on a calendar of dates that incidents of abuse occur.

- Don’t post information about them on social media that could be used to identify them or where they spend time.

- Help them learn about their formal legal rights through resources like Women’s Law, which provides information on domestic violence laws and procedures.

- With their permission, ensure that others in the buildings where the survivor lives and works are aware of the situation, including what to do (and what not to do) during a moment of crisis or confrontation with an abusive partner.

As an immigrant to the U.S., what are the legal rights available to me if I face abuse?

(Read more on uscis.gov. Consult an attorney to understand how these options may affect you)

- Under all circumstances, domestic violence, sexual assault and child abuse are illegal in the United States. All people in the United States (regardless of race, color, religion, sex, age, ethnicity, national origin or immigration status) are guaranteed protection from abuse under the law. Any victim of domestic violence—regardless of immigration or citizenship status—can seek help. An immigrant victim of domestic violence may also be eligible for immigration-related protections.

- All people in the United States, regardless of immigration or citizenship status, are guaranteed basic protections under both civil and criminal law. Victims of crime, regardless of their immigration or citizenship status, can access help provided by government or non-governmental agencies, which may include counseling, interpreters, safety planning, emergency housing and even monetary assistance. Laws governing families provide you with:

- The right to obtain a protection order for you and your child(ren).

- The right to legal separation or divorce without the consent of your spouse.

- The right to share certain marital property. In cases of divorce, the court will divide any property or financial assets you and your spouse have together.

- The right to ask for custody of your child(ren) and financial support.

- Under U.S. law, any crime victim, regardless of immigration or citizenship status, can call the police for help or obtain a protection order.

If you are a DV victim, help is at hand

If you are in Georgia:

- For Indian citizens – Indian Consulate in Atlanta: 1-404-963-5902 Ext. 124

- For South Asian community - Raksha: 1-866-725-7423 (Raksha.org)

- Georgia 24-Hour Statewide Hotline: 1-800-334-2836 (1-800-33-HAVEN)

- Georgia Coalition Against Domestic Violence (Gcadv.org/resources)

- Live Safe Resources (LiveSafeResources.org)

- Domestic Shelters (DomesticShelters.org)

- Criminal Justice Coordinating Council (Cjcc.georgia.gov/grants/grant-subject-areas/domestic-violence/resources)

For a more comprehensive listing of national information resources and helpful agencies for South Asians, read here: tinyurl.com/TheWomanIncSafetyNetwork)

Here are some national helplines:

- The National Domestic Violence Hotline (ndvh.org)

1-800-799-7233 (SAFE) - National Sexual Assault Hotline (rainn.org)

1-800-656-4673 (HOPE) - National Suicide Prevention Lifeline (suicidepreventionlifeline.org

1-800-273-8255 (TALK)

[This story was originally published by Khabar.]