Note: This story is part of 'Gone too soon,' a series that examines why Native Americans die a generation younger than their white neighbors in Montana. With support from the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2023 National Fellowship, Lee Montana newspapers spent six months reporting on the factors that contribute to a lower life expectancy and what could help close the gap.

'You don't want to be part of this club': In Fort Peck, death has become part of life

The story was originally published by the Missoulian with support from our 2023 National Fellowship's Dennis A. Hunt Fund for Health Journalism.

WOLF POINT — Two weeks after burying her grandmother in the fall of 2020, Jen Medicine Cloud’s brother and sister were both hospitalized with COVID.

Jen’s sister was at the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota, and her brother, Scobey Baker, was at a hospital in Billings. She remembers when he called her crying the night before he was put on a ventilator.

“He was so scared,” she said through tears.

As an older brother, Scobey had always been Jen’s protector. While he’d struggled with alcoholism for decades, he’d been sober for the last two years. For his family, his sobriety felt like a gift.

At her home in Wolf Point on Oct. 26, 2023, Jen Medicine Cloud, 44, looks at a painting of her late nephew, Scobey John Baker, who died in a car accident at 12. Medicine Cloud raised her nephew since he was an infant, and her life hasn’t been the same since his death.

ANTONIO IBARRA OLIVARES, Missoulian

“We got our brother back, and then he was just gone,” she said.

Native Americans have the lowest life expectancy of any racial or ethnic group in the U.S. In Montana, where Native Americans comprise 6.7% of the population, Indigenous people die a generation younger than their white neighbors.

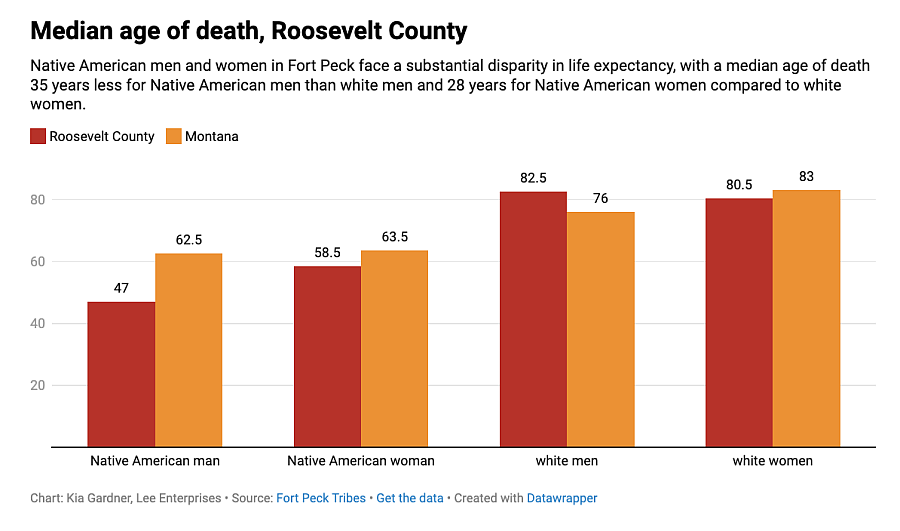

Pre-COVID data reveals that, nationally, Native Americans die, on average, at age 71.8. In Montana, Native Americans die, on average, at 61. And on the Fort Peck Reservation, Natives typically die at 52.7.

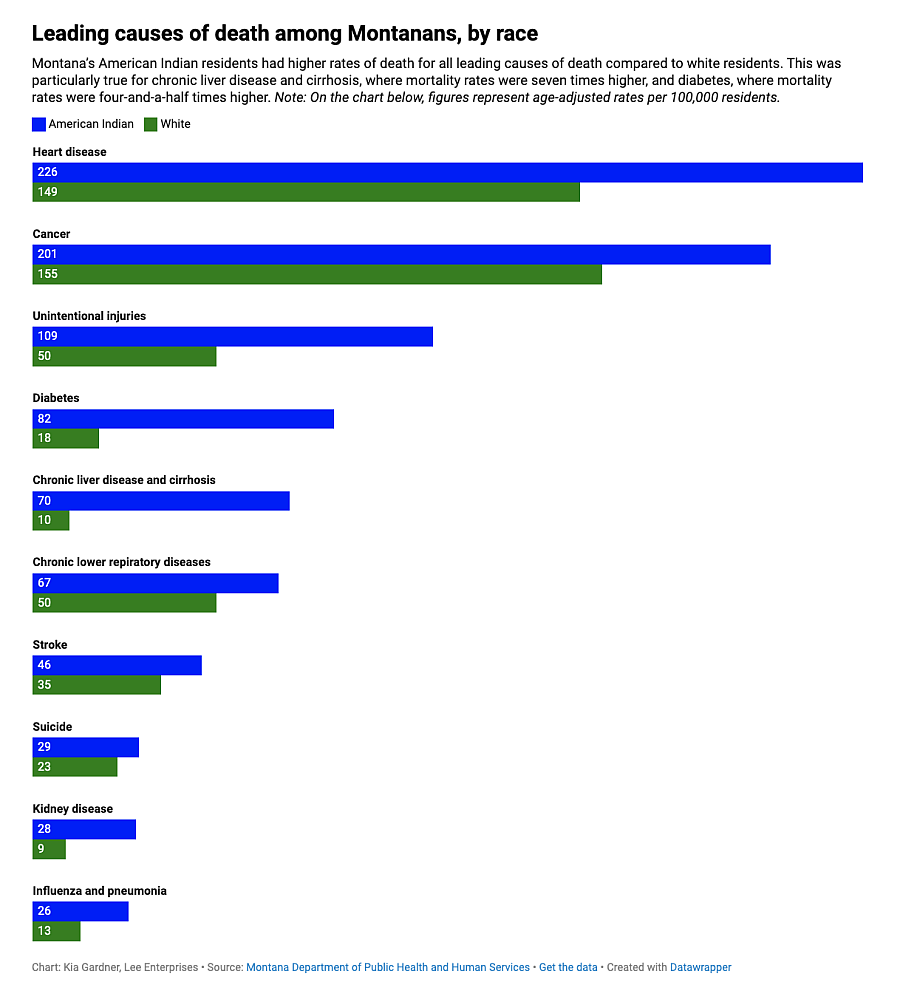

Indigenous people in Montana are more likely to die from heart disease, cancer, unintended injury, diabetes, cirrhosis, respiratory disease, stroke, suicide, kidney disease and the flu than white residents. And when COVID came to Montana in 2020, Indigenous people were 11.6 times more likely to die from the virus than their white neighbors.

Experts say inadequate care, food deserts, discrimination at the doctor’s office, poverty and rurality are among the factors contributing to the crisis. And while tribal leaders have raised the issue for years, they say improving health outcomes simply isn’t a priority among state and federal leaders.

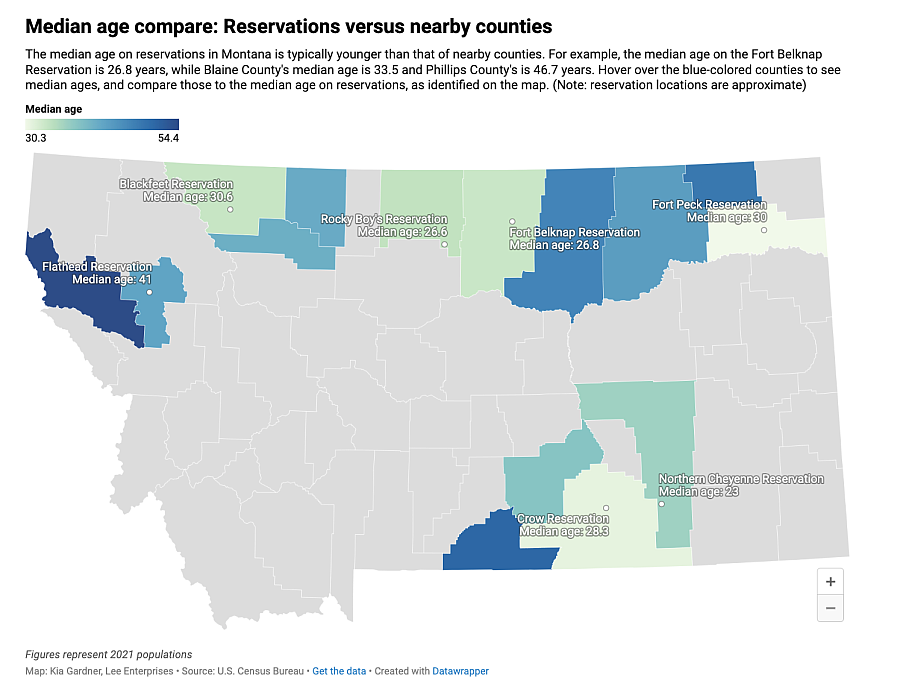

Located in the northeast corner of Montana and home to about 10,100 people, the Fort Peck Reservation stretches 110 miles long and 40 miles wide. There — where 26 could be considered middle-aged — a barrage of premature, preventable deaths tear at the living.

Schools and tribal offices close for funerals. On birthdays and graduations, people include visits to loved ones’ gravesites in their celebrations. Even as residents drive through the reservation on Highway 2, death dominates the landscape. Billboards warn of heart attack, suicide, alcohol, drug use.

Indigenous parents are dying in their 40s. Grandparents, who assume guardianship of their grandchildren, are dying in their 50s and 60s, leaving too many children and teenagers to grow up unsupported.

But some don’t get to grow up, dying young from car crashes, violence, addiction or suicide.

The cycle of premature death weathers and isolates Indigenous parents and grandparents on the Fort Peck Reservation. It disrupts the health, education and careers of young people, who, in the absence of accessible mental and behavioral health services, may turn to drugs or alcohol to cope.

Experts say these deaths steal from the workforce, contribute to homelessness, perpetuate violence and reinforce economic insecurity.

View from Highway 2 of the sun rising above the horizon during a cold and frosty morning on the Fort Peck Reservation on Oct. 27.

ANTONIO IBARRA OLIVARES, Missoulian

‘Take me!’: Premature death hurts families

On the same day as Scobey’s funeral service just down the road in Wolf Point, Frances Weeks was washing dishes and looking out her kitchen window when she saw her 28-year-old son, Cody, run by. She didn’t see the person chasing him.

Frances heard a gunshot. Then an ambulance siren.

Frances Weeks stands in front of her kitchen sink as she recounts a memory from 2020. When she was washing the dishes, she saw her 28-year-old son, Cody, run by. She later learned he was shot to death. In 2017, homicide was the fourth leading cause of death for Native American men ages 20 to 44, and from 2011 to 2015, Native Americans in Montana were more than four times as likely to die from homicide than white Montanans.

ANTONIO IBARRA OLIVARES, Missoulian

She rushed to the hospital and found Cody laying in a bed. Her mind jumped to the days when he’d leap out to scare her in the hallways of her house.

“Let him be messing with me now,” she thought.

But then it hit her. Her son — who had been invited to four different proms, who had cheered his basketball teammates on when he was injured, who kept everyone’s secrets, who wanted to one day work with autistic children — was dead.

Frances fell to her knees on the cold hospital floor and screamed.

“Take me!” she yelled through tears. “Please!”

In 2017, homicide was the fourth-leading cause of death for Native American men ages 20 to 44. And from 2011-15, Native Americans in Montana were more than four times as likely to die from homicide than white Montanans.

Frances Weeks, 55, a mother and grandmother on the Fort Peck Reservation, sits at her home in Wolf Point on Oct. 24, 2023. She wipes away tears while recounting the life stories of six family members who passed away at an early age from health-related complications, accidents and homicide.

ANTONIO IBARRA OLIVARES, Missoulian

Frances is 5-foot-7 and slender. Her copper hair has streaks of gray, she wears big, cat-eye glasses, and everyone calls her auntie or grandma. When Cody died, she stayed busy. She gathered community members to call for justice in his killing. She planned a funeral. She scrambled to arrange care for Cody’s three children.

She didn’t realize at the time that Cody’s sudden death put her other children at risk, too.

Annie Belcourt, Native American Studies chair at University of Montana, told Lee newspapers in July that violence, and the trauma and stress associated with it, can have far-reaching consequences, affecting someone’s health and quality of life.

“People who experience trauma may struggle with coping strategies,” she continued. “Maladaptive things may help them functionally avoid thinking about it. It could be substance abuse, gambling or working a ton to help you avoid thinking or feeling a complicated trauma response.”

Cody’s death rolled like a wave through the community and crashed on his younger brother Quentin.

The gravesite of Cody James Weeks Combs, Frances Weeks’ late son, at a cemetery off of Highway 2 between Wolf Point and Poplar on the Fort Peck Reservation. Cody was and shot and killed in 2020 near his home in Wolf Point.

ANTONIO IBARRA OLIVARES, Missoulian

Quentin, a strapping football star and Homecoming king at Chemawa Indian School in Oregon, returned to the Fort Peck Reservation when a close friend died by suicide.

Frances said Quentin used alcohol to cope with loss, drinking nearly every day in the wake of his brother’s death.

Soon, Quentin’s liver and kidneys began to fail. Frances took him to a hospital on the reservation and tried to help him detox. While the reservation has a recovery center, it does not provide inpatient services and struggles to meet a high demand of needs. Quentin was flown to a hospital in Billings, where Frances said his condition briefly improved. But by that time, it was too late.

"It was so hard for him to understand that there was no coming back from this," she said.

In April, Quentin died at 26 of liver and kidney failure. On the reservation, the death rate for chronic liver failure or cirrhosis is seven times higher than that in Montana.

Frances Weeks holds a poster of photos and memories honoring her late son Quentin Weeks Combs, who died at 26 of liver and kidney failure. On the reservation, the death rate for chronic liver failure or cirrhosis is seven times higher than that in other communities in Montana.

ANTONIO IBARRA OLIVARES, Missoulian

‘We ... needed help now’: Mental health resources in short supply

In July, eight months after Jen’s grandmother and brother died of COVID, her world was again shattered when her father and 12-year-old nephew were killed in a car accident.

Jen had raised her nephew, Scobey John Baker (son of her late brother Scobey Baker), since he was an infant.

After the deaths of her brother and grandmother, Jen and her family avoided cultural events and stopped powwow dancing, as is customary in some Indigenous cultures.

As the one-year anniversary of their deaths approached, Jen prepared to hold a “wiping of the tears” ceremony, which is meant to bring people out of mourning. After the ceremony, she and her children would be able to dance again.

Jen Medicine Cloud pets her dog Nova at her home in Wolf Point on the Fort Peck Reservation as she recounts the stories of family members who died too soon from preventable deaths.

ANTONIO IBARRA OLIVARES, Missoulian

But Jen didn’t get to return to dancing that year. Scobey John’s sudden death nearly destroyed her. From a young age, it had always seemed like Scobey John was destined to be a leader. As a child, he would tie strings around his stuffed animals, and, like a puppet master, he’d have the animals mimic sundances.

Scobey John joked often — one time giving out "Indian names" to white girls on the playground — and he cared deeply for others, once found praying for his classmates when he was 8 years old.

His life, too, had been touched by death. His mother died of cirrhosis at 25, and his father, Scobey Sr., died of COVID when Scobey John was 11.

Kai Teague, who was adopted into the Medicine Cloud family, said when Scobey John died, the whole family felt hopeless.

Jen Medicine Cloud, left, and Kai Teague, right, who was adopted into the Medicine Cloud family, recount memories of their late family member, Scobey John. Teague said the whole family felt hopeless after losing Scobey John and other family members.

ANTONIO IBARRA OLIVARES, Missoulian

“It sounds bad, but you don't get to just die,” Teague said. “I’m pretty sure that as a collective, if we could’ve, we probably all would’ve just gone.”

Jen’s daughter was suicidal after her brother’s sudden death and decided to leave college in North Dakota to move home and be with family.

“I was scared,” Jen recalled. “(We’d) go to sleep and pray that she was OK. And we’d make sure she was breathing the next morning. That’s scary.”

Phoebe Blount, who helped launch a crisis helpline on the reservation, said it's not uncommon for family members to experience suicidal ideation — or to turn to drugs and alcohol — after experiencing trauma and loss.

“It’s that hopelessness,” she said. “And it’s normalized. … Because it happens so much, (it becomes) just part of the consequences of life.”

For many on the reservation, getting help isn’t easy. And when people spend significant time and energy surmounting barriers to access health care, experts say they may not have the capacity to work or to contribute to the community.

While several tribal programs provide mental health services, community members say they need more clinicians. According to a 2016 report, for every 1,030 people on the reservation, there is one mental health provider. By comparison, in Montana — a state that recently claimed the second-highest suicide rate in the country — there was one mental health provider for every 399 people.

As the country promotes a national suicide hotline — reachable at 988 — tribal members in Montana say they face barriers in using the service. As of now, when people on the Fort Peck Reservation call 988, someone 350 miles away in Great Falls will likely answer. But whoever answers may not necessarily understand the unique challenges of living in the Fort Peck community or what it’s like being Native American in Montana.

It’s one reason why the Fort Peck Tribes launched a new crisis helpline on the reservation. Now, when people call 406-653-2000, a fellow community member will be on the other end. Experts say bridging the cultural gap can make all the difference.

At the time, Jen didn’t anticipate the far-reaching consequences of a traumatic family event. Vicki Bisbee, former counselor at Southside Elementary School in Wolf Point and the 2019 Montana Counselor of the Year, has seen firsthand how premature death and subsequent trauma and grief can disrupt education for young people.

If a student on the reservation lost a parent, Bisbee said they may move 300 miles south to Billings to live with another relative. And if that relative died, the student may move back to the reservation to live with someone else.

Jaidyn Alvstad, 18, is a citizen of the Fort Peck Assiniboine and Sioux Tribes and a senior at Savage High School in northeast Montana. Like many Indigenous people in Montana, Jaidyn has lost family members too soon in preventable deaths. In an interview with The Missoulian, Alvstad talks about her family's story and how they navigated the loss of family members.

Antonio Ibarra Olivares

This kind of disruption can be especially difficult for school-aged youth, Bisbee said, adding that traumatic events, like the premature death of a family member, can contribute to chronic absenteeism. At the high school level, Bisbee said about 10 students drop out each year.

“So that’s 40 kids over four years,” she reasoned. “And where do they go? Usually the streets or drugs. And they don't work. … We’ve noticed that people living on the streets are getting younger and younger.”

Fortunately, Jen’s daughter didn’t fall through the cracks.

Because Jen had health insurance through her job, she took her daughter to Northeast Montana Health Services, a hospital on the reservation. Teletherapy felt like a godsend. Now, Jen’s daughter is substitute teaching and working toward a bachelor’s degree.

Jen fears her daughter may have faced a different outcome if she hadn’t been able to access appropriate mental health services. About one-third of Fort Peck Reservation residents do not have health insurance. “(Indian Health Service) is so overwhelmed with people,” Jen said. “We couldn’t wait … (my daughter) needed help now.”

A painting of Scobey John Baker, who died in a car accident when he was 12 years old, leans against the wall at Jen Medicine Cloud’s home in Wolf Point. Scobey John was the son of Medicine Cloud’s late brother Scobey Baker who died of COVID.

ANTONIO IBARRA OLIVARES, Missoulian

‘You don’t want to be part of this club': The resounding pain of loss

Nine months after Quentin’s death, Frances continues to raise her 7-year-old grandson, who she’s cared for since infancy. She’s weathered by grief and by persistent back pain from her decades in tribal law enforcement.

After Scobey John and Jen’s father were killed, Jen returned to work teaching first graders. While the children brought her solace, Jen felt hollow. She wonders whether she should’ve been teaching at all while she grieved.

Frances raised money to travel for back surgery, but with limited mobility, she can’t bring food to people experiencing homelessness or take her grandson to the park like she used to. Jen tracks her loved ones’ locations on her phone. She must know where everyone is at all times, fearing something bad will happen to them.

At 55, Frances is 3 1/2 years younger than the average age at which Native women die on her reservation. At 44, Jen is the same age her brother was when he died. The idea of death haunts her. She’s afraid she’ll die while her kids still need her. She doesn’t know whether she’ll be able to survive another loss in the family.

Scobey John’s powwow bustle hangs above Jen’s mantle in her house. Six blocks away, Frances keeps Cody and Quentin’s belongings in a room of her house. Their old clothes, trophies, photos and poster boards are piled so high that they barricade the door shut.

“You don’t really move on,” Frances said. “For me, it’s been eye-opening to know that everybody feels the same way. Everybody has that hurt, but you don’t want to be part of this club.”

Frances Weeks, right, exits a minivan as friend Tracey Rider assists Weeks with her walker outside Chief Redstone Health Center in Wolf point on the Fort Peck Reservation on Oct. 24, 2023. After getting back surgery, Weeks receives help from friends and family to get to and from her medical appointments.

ANTONIO IBARRA OLIVARES, Missoulian

Photos: Fort Peck families grapple with premature and preventable family deaths

At her home in Wolf Point on Oct. 26, 2023, Jen Medicine Cloud, 44, looks at a painting of her late nephew, Scobey John Baker, who died in a car accident at 12. Medicine Cloud raised her nephew since he was an infant, and her life hasn’t been the same since his death.

ANTONIO IBARRA OLIVARES, Missoulian

A painting of Scobey John Baker, who died in a car accident when he was 12 years old, leans against the wall at Jen Medicine Cloud’s home in Wolf Point. Scobey John was the son of Medicine Cloud’s late brother Scobey Baker who died of COVID.

ANTONIO IBARRA OLIVARES, Missoulian

Jen Medicine Cloud pets her dog Nova at her home in Wolf Point on the Fort Peck Reservation as she recounts the stories of family members who died too soon from preventable deaths.

ANTONIO IBARRA OLIVARES, Missoulian

Jen Medicine Cloud, left, and Kai Teague, right, who was adopted into the Medicine Cloud family, recount memories of their late family member, Scobey John. Teague said the whole family felt hopeless after losing Scobey John and other family members.

ANTONIO IBARRA OLIVARES, Missoulian

Frances Weeks, 55, a mother and grandmother on the Fort Peck Reservation, sits at her home in Wolf Point on Oct. 24, 2023. She wipes away tears while recounting the life stories of six family members who passed away at an early age from health-related complications, accidents and homicide.

ANTONIO IBARRA OLIVARES, Missoulian

Frances Weeks stands in front of her kitchen sink as she recounts a memory from 2020. When she was washing the dishes, she saw her 28-year-old son, Cody, run by. She later learned he was shot to death. In 2017, homicide was the fourth leading cause of death for Native American men ages 20 to 44, and from 2011 to 2015, Native Americans in Montana were more than four times as likely to die from homicide than white Montanans.

ANTONIO IBARRA OLIVARES, Missoulian

Frances Weeks holds a poster of photos and memories honoring her late son Quentin Weeks Combs, who died at 26 of liver and kidney failure. On the reservation, the death rate for chronic liver failure or cirrhosis is seven times higher than that in other communities in Montana.

ANTONIO IBARRA OLIVARES, Missoulian

The gravesite of Cody James Weeks Combs, Frances Weeks’ late son, at a cemetery off of Highway 2 between Wolf Point and Poplar on the Fort Peck Reservation. Cody was and shot and killed in 2020 near his home in Wolf Point.

ANTONIO IBARRA OLIVARES, Missoulian

Frances Weeks uses a walker to go down a ramp installed outside her home in Wolf Point as Weeks makes her way to her friend Tracey Rider’s car en route to a doctor’s appointment on Oct. 24, 2023. Due to limited mobility from health complications, Weeks gets car rides from family and friends to get to and from her medical appointments on the Fort Peck Reservation.

ANTONIO IBARRA OLIVARES, Missoulian

Frances Weeks, right, exits a minivan as friend Tracey Rider assists Weeks with her walker outside Chief Redstone Health Center in Wolf point on the Fort Peck Reservation on Oct. 24, 2023. After getting back surgery, Weeks receives help from friends and family to get to and from her medical appointments.

ANTONIO IBARRA OLIVARES, Missoulian

View from Highway 2 of the sun rising above the horizon during a cold and frosty morning on the Fort Peck Reservation on Oct. 27.

ANTONIO IBARRA OLIVARES, Missoulian

Deyo Four Bear, 23, and a few of his friends works out at the Thundering Buffalo Health and Wellness Center in Poplar on Oct. 23, 2023. Four Bear has been coming to Thundering Buffalo Health and Wellness Center since it opened two years ago. He comes to the gym almost every day to stay healthy. “Since I’ve started coming, I’ve seen a lot of progress.”

ANTONIO IBARRA OLIVARES, Missoulian

Jaidyn Alvstad, 18, a senior at Savage High School, smiles as she plays with her cat, Roo, at her home in the town of Savage, Montana on Oct. 24, 2023. Alvstad picked Roo up from her grandparents house in Wolf Point after cleaning it out after her grandmother’s death. When Alvstad lost her father at 38, her grandparents became her rock. When her grandparents both died in their 50s, Alvstad struggled. “You don’t come out of that without scars,” she said.

ANTONIO IBARRA OLIVARES, Missoulian

Jaidyn Alvstad keeps obituaries of her loved ones stashed in a wooden box that her stepfather gave her. In the bottom left corner is a sketch her father Jared Alvstad did of Sitting Bull before he died.

ANTONIO IBARRA OLIVARES, Missoulian

Jaidyn Alvstad puts away obituaries of her loved ones which she stashes in a wooden box gifted by her stepfather while recounting stories about her late family members on Oct. 24, 2023 in Savage, Montana. Jaidyn’s biological father, Jared Alvstad, died at 38 of liver failure. Her grandfather died of liver and kidney failure at 58 and her grandmother died at 59 of lung complications.

ANTONIO IBARRA OLIVARES, Missoulian

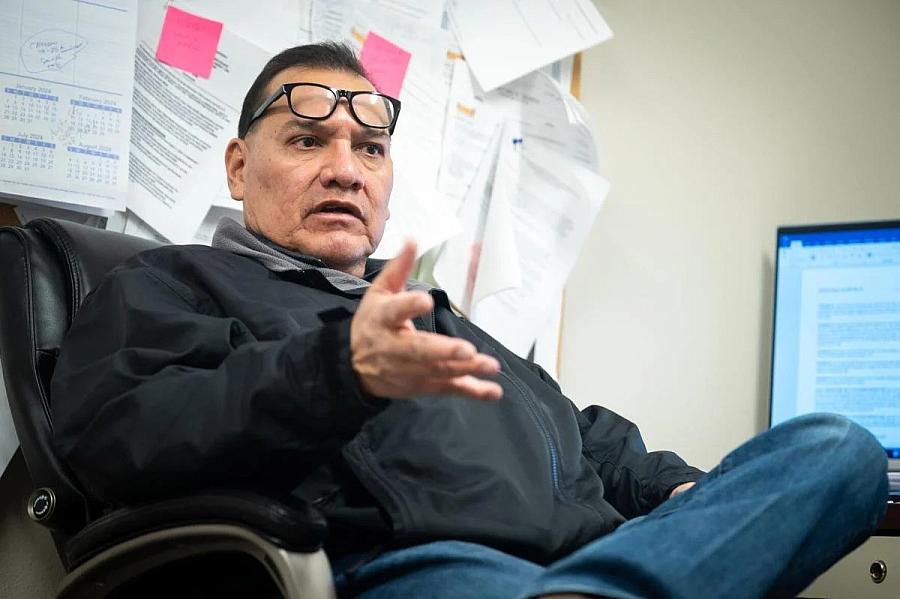

Dennis Four Bear, director of the Fort Peck Tribal Health Department in Poplar. Four Bear the tribes spent about $700,000 last year on medical assistance for members. He said distance to and from health care facilities and a lack of providers on the reservation contribute to health disparities throughout the Fort Peck Reservation.

ANTONIO IBARRA OLIVARES, Missoulian

Commuter buses with Fort Peck Transit help transport patients to and from their appointments at Verne E Gibbs Health Center in Poplar on the Fort Peck Reservation. The health center is part of Indian Health Services.

ANTONIO IBARRA OLIVARES, Missoulian

View of the Fort Peck Tribal Dialysis Unit located on the Fort Peck Indian Reservation in Poplar, Montana. The facility provides chronic hemodialysis to individuals with End Stage Renal Disease in Northeast Montana.

ANTONIO IBARRA OLIVARES, Missoulian

Robyn Nygard is the Renal Administrator of the Fort Peck Tribal Dialysis Unit, which serves the reservation and several rural communities nearby. Some tribes in Montana don’t have dialysis nearby, so patients may have to leave the community several times a week for care.

ANTONIO IBARRA OLIVARES, Missoulian

The Fort Peck Tribal Dialysis Unit is equipped with several dialysis machines to serve patients across the Fort Peck Reservation.

ANTONIO IBARRA OLIVARES, Missoulian