Young Men in Military Almost Twice as Likely to Die By Suicide as Civilian Peers

This story was completed as a project for the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism 2021 Data Fellowship.

Other stories include:

Over Six Years, There Have Been More Than 30 Suicides at Camp Pendleton

Women In Military More Than Twice as Likely to Die By Suicide as Civilians

Jodee Watelet looks at a shelf dedicated to her son, Kellen Watelet, in her home in Mesquite, Nev., on Friday, May 20, 2022.

Photo by Miranda Alam for Voice of San Diego

If you or someone you know might be considering suicide, please call: 800-273-8255.

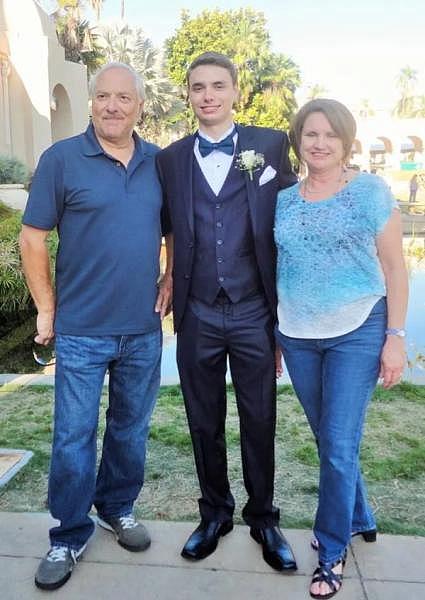

Kellen Watelet was one of those people who make it look effortless. He did well in school, in sports and making friends. He had an easy smile. He loved Hawaiian shirts, sneakers and motorcycles.

“I always looked up to Kellen, to be honest. I was always trying to get to his level. I wanted to do better when I was with him. But it was really hard with how gifted he was,” said his cousin, and brother by adoption, Matt Donohoe.

Watelet was both adventurous and practical, said his parents. After high school, he had two priorities: getting out of the house and setting himself up for the future. He had scored near perfect on a military aptitude test, so he went to see a Navy recruiter.

Photos courtesy of Steve Watelet.

The recruiter presented an option that appealed to his sense of adventure and could give him valuable skills. The recruiter offered Watelet a large signing bonus to train as a cryptologic technician. Essentially, he’d be working in cyber warfare and if he played it right, he’d be able to parlay that work into a high-paying job later.

The Navy sells it this way: “You fight in the battlespace of the future. Use state-of-the-art tech to perform offensive and defensive cyber operations, investigating and tracking enemies while also protecting our networks from attacks,” reads an excerpt on its website.

Troops in the battlespace of the future do not face physical harm, but they experience acute psychological strain that military leaders are coming to better understand. Watelet did not, and could not, say much to his family about the work he was doing. From what they could tell, he spent his days inside a facility in Point Loma, constantly on-guard to cyber threats from other countries. Even though Watelet didn’t say much about the pressure, his mother knew it was there. Stress within the field is “common, persistent and disabling,” according to one Department of Defense report.

“[Kellen] talked to me a lot about how stressful his unit was,” said Donohoe. “He was good at his job and it sounded like a lot of stuff got put on him.”

Photos by Miranda Alam for Voice of San Diego

He started drinking and using Molly. He wanted to escape, his mom Jodee believes. “It wasn’t like him,” she said. “Those are all the signs: erratic behavior, doing drugs, heavy drinking.”

But signs of what? Even those who knew him best did not know how to interpret them.

Then on Jan. 6, 2020, a little more than a month before his 23rd birthday, Watelet took his own life. He was the first sailor or Marine that year to die by suicide in San Diego County – but his death represents part of a much larger trend. The national suicide rate for active-duty men aged 17 – 25 was roughly 46.1 per 100,000 in 2020, according to data obtained by Voice of San Diego through a Freedom of Information Act request. That’s 80 percent higher than the suicide rate for civilian men – 25.6 per 100,000 – in the same age bracket, according to recently released data by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Military officials declined to provide local numbers and would not confirm whether they even track suicide deaths at the local level. Voice analyzed local death certificates of troops aged 17 – 25, but the raw number of suicides was too low to form a reliable rate. Suicides at the local level did, however, increase in 2020.

Historically, military suicide rates have been much lower than the general population. But the rate has been rising in recent years – especially among young men.

In its 2019 Annual Suicide Report, the Department of Defense acknowledged that young military members are at “higher risk for suicide.” But the annual reports do not provide age and gender specific breakdowns in a way that allow for age-specific comparisons like Voice performed.

Instead, the report emphasizes that age and gender-adjusted suicide rates in the military are comparable to the general population.

“After accounting for age and sex,” the report reads, “[active-duty] suicide rates are statistically comparable to the U.S. population rates.”

No one totally understands why military suicide rates are increasing. And despite hundreds of millions of dollars in research and prevention programs targeted directly at the military, the problem isn’t improving.

“Arguably, the most significant challenge is a cultural challenge,” said M. David Rudd, a former Army psychologist and former president of the University of Memphis. “As a warrior culture, it’s about selfless sacrifice and personal courage – the team being more important than the individual. But if you feel like you can’t hold up your end of the bargain or feel like you’re the weakest link in the chain, it amplifies feelings of failure and shame.”

**

Veteran suicide, as a public health crisis, is already a part of the public consciousness. Many can picture a war vet wrestling with post-traumatic stress, struggling to connect in the civilian world and dealing with needless bureaucratic delays in care – whether the picture is true or not.

But the current phenomenon is different. Young people, 25 and under, are most at-risk to die by suicide among active-duty military members. Most of these young men and women have not done active combat tours. In many cases, they take their own lives on military bases, where they are surrounded by others who understand the unique pressures of military life and, in theory, have direct access to the services they need.

Military leaders prided themselves for decades on the idea that troops were more fit – physically and mentally – than civilians. Up until the early 2000’s, the age and gender-adjusted suicide rate for troops, as a whole, was significantly lower than for civilians. But then the rate started creeping up. For the last ten years, the military’s age and gender-adjusted suicide rate has been roughly the same as civilians.

Items memorializing Kellen Watelet, Steve and Jodee Watelet’s son, are displayed in their home in Mesquite, Nev., on Friday, May 20, 2022. / Photo by Miranda Alam for Voice of San Diego

In 2019 and 2020, civilian suicides rates went down as military suicide rates went up.

Military leaders seem confounded by the rise. They have poured money and manpower into solutions. Soldiers are more likely than ever to see messages about the importance of mental health and speaking up when they have a problem.

“One of the things that is bedeviling about suicide is that it’s often very hard to connect dots in causality – what leads somebody to make that decision,” John Kirby, who was the Pentagon press secretary at the time, told the Associated Press last year. “It’s difficult to denote specific causality with suicide on an individual basis, let alone on an institutional basis.”

To Rudd, the military’s failure to address mental health challenges is not so mysterious.

Feelings of shame and failure, and feeling like a burden, are some of the most common precursors to a suicide attempt. These feelings – for someone who believes they aren’t living up to the military’s warrior culture – are amplified, he said.

And indeed, for all the new rhetoric from the military to its enlisted members about suicide awareness, the rest of the training and cultural response that soldiers receive from leadership and their peers overwhelms it.

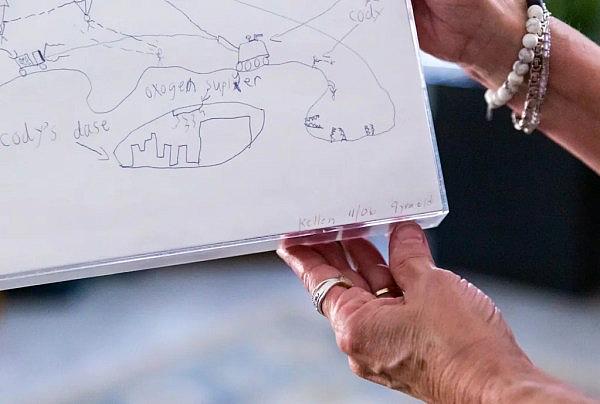

Matt Donohoe with his cousin Kellen Watelet. Courtesy of Steve Watelet.

Donohoe, Watelet’s cousin, decided to join the Marine Corps shortly after Watelet joined the Navy. He saw firsthand how the values of a warrior culture are at odds with mental health needs.

“You’re trained to bottle up your emotions and keep pushing from day one,” said Donohoe. “Don’t get me wrong, the military has huge amounts of resources. You see it everywhere on suicide and harassment. They preach about open doors and how ‘You can come talk to us anytime, about anything.’ But it doesn’t work like that.”

The fundamental tenets of military training – to protect one’s brothers and sisters, even to the last breath, if necessary – implicitly signal that nothing, not even sanity, is more important than serving the unit.

Expressing serious mental health concerns is a ticket to other than honorable discharge rather than promotion, said Donohoe.

“Guys bottle it up cuz they wanna stay in, they wanna get promoted,” he said.

At least 37 percent of active-duty troops believe seeking mental health support will “probably or definitely” damage their career, according to one 2011 report.

All this creates a situation where implementing treatments, even those that are proven effective, is nearly impossible, said Rudd, the former Army psychologist.

“We have spent significant amounts of money developing treatments and interventions that are effective,” he said. “But we’ve developed treatments that are incredibly hard to implement, because of the culture.”

Take, for example, a service member who is diagnosed with generalized anxiety disorder. That person should be put on restricted duty for 90 days and receive weekly therapy, said Rudd. More than 80 percent of people’s symptoms improve after such treatment. But many commanding officers are not eager to carve out that time, said Rudd, when it conflicts with the operational demands of a unit.

“What [military leaders] ought not to do is say they support mental health care and then block those treatments every single time,” said Rudd.

Some military leaders disagree they are denying troops care.

Mario D’Aliesio is the branch head of behavioral health for Marine and Family Programs at Camp Pendleton in Oceanside, the largest Marine installation in the United States. He told me that commanders, in general, want to get their enlisted troops the help they need.

“They know that if they don’t take care of things in garrison, they’ll have to take care of it when they’re deployed. And when they’re deployed and someone doesn’t do well, it takes a lot of resources to get that individual back into the rear to be taken care of,” said D’Aliesio.

At least on Camp Pendleton, D’Aliesio said he believed mental health services were on the right track. He said any Marine who needs an evaluation can get one immediately – and the average wait time to see a counselor, not including the initial evaluation, is 19 days.

But even when service members do get time off work to get the treatment they need, they can end up in a shame spiral.

Former Petty Officer Third Class Jalitza Cardona worked as a ship’s mechanic. When she started encountering serious depression and suicidal thoughts, she told her commanding officer, just as she was supposed to. She got connected to a Navy psychologist and started getting weekly therapy.

But privacy is not easy to come by in military life. Cardona’s ship was on deployment.

“You can’t compartmentalize. People knew everything about you, down to the medication you’re taking, because of the fact that we were all on a tin can together for so long,” said Cardona.

Her depression was already making her feel isolated. But her need to go get treatment only made things worse.

The other sailors in her small unit said to her, in effect: “‘You’re continuously leaving to get seen by a psychiatrist. So we can’t depend on you at all,’” said Cardona.

It turned into a violent feedback loop. Cardona’s depression was compounded by feelings of shame and failure.

She tried to take her own life with pills. When she woke up in a hospital, her first reaction was anger, she said. “I was pissed it didn’t work,” she said, “because I knew I would have to go back to the life I had.”

Some immediately regret trying to kill themselves. For Cardona, it was a long road out of serious depression – but one full of meaning. Today, she works at Courage to Call, a San Diego organization dedicated to helping service members and vets with mental health challenges.

“I want others to know that there is a lighter side to the dark side they’re experiencing,” she said. “When I was experiencing it, I thought, ‘That’s not possible.’ But I want others to know it is possible, and that’s why I do this work.”

**

Suicides in 2020 spiked across the active-duty military. More than one person a day – 384 in total – died by suicide. Preliminary reports for 2021 suggests the numbers came down slightly, but are still above civilian rates.

Military leaders aren’t sure whether the 2020 spike was related to the pandemic.

Early on, service members were barred from traveling, except for cases of emergency. On-base gyms were closed, as were most communal gathering spaces. All the traditional ways that a soldier might fill their free time were not available. In other words, their lockdown was not so different than the one civilians faced.

By September 2020, officials could see suicides were on track to be significantly higher than the previous year.

“I can’t say scientifically, but what I can say is — I can read a chart and a graph, and the numbers have gone up in behavioral health related issues,” Army Secretary Ryan McCarthy told the Associated Press.

When all the deaths were counted, suicide had risen by 10 percent from the previous year. But military officials walked back their messaging. They said COVID may have increased risk factors, but were unsure whether it caused the increase.

Mental health professionals feared an increase in suicide among civilian adults and young people in 2020. But recently released data from the CDC shows that in fact the suicide rate among civilians went down by 3 percent.

Lance Corporal Michael Soesbee’s story illustrates the complicated nature of the causes behind suicide – and how they can be amplified by life in the military.

Michael and his wife Brooke Soesbee moved into base housing on Camp Pendleton just after the pandemic began. Michael’s life continued as normal to a certain extent, Brooke said. He still went to his job as a helicopter mechanic every day and he still saw his friends.

Michael Soesbee and his wife Brooke. Photos courtesy of Brooke Soesbee.

Brooke, however, had just moved to a military base for the first time in her life during the middle of a pandemic. She walked their dog, watched a lot of tv and talked to people from back home in North Carolina on the phone.

Michael was struggling. He felt poorly treated by some of his fellow Marines, he wrote. And one of his commanding officers had told him he was bad at his job, he told Brooke. He turned inward and would come home and play video games, instead of spend time with her. When he wasn’t playing video games, he was often angry, she said.

Brooke started taking trips back to North Carolina and their relationship became even more turbulent. She told him she wasn’t sure she could come back.

Michael, who was 20 years old, took his own life on Sept. 15, 2020. In a letter, he wrote: “Joining the Marine Corps is one of the largest mistakes I’ve ever made. I lost everything, time with my family, my freedom, the love of my life and the love of my own life.”

Michael had a difficult childhood, said Brooke. The Marine Corps made him feel isolated and insufficient. Pandemic life made Brooke isolated. Their relationship suffered and strained.

It’s almost always impossible to tie a suicide to any one cause. But it seems clear the pains of civilian life that are often a precursor to suicide – stress, shame, inadequacy, depression, feeling like a burden – become amplified by life in the military.

**

If Kellen Watelet was the light in his family’s life, his death was the fog.

Confusion, sadness and anger hung over his mother, father and cousin’s lives.

His father Steve continued to go to work at first, on auto-pilot. Initially, he told people Kellen died in a training accident. He had vivid dreams of Kellen walking around the house.

Jodee and Steve Watelet at their home in Mesquite, Nev., on Friday, May 20, 2022. / Photo by Miranda Alam for Voice of San Diego

His mother Jodee couldn’t get off the couch. She had struggled with depression as a young person and it came back to her in a tidal wave.

The parents described a sensation they called “grief brain.” They frequently forgot what they were supposed to be doing. Their short-term memories were shot.

His cousin Matt was in shock, too. He called Kellen three times after he found out, because he was sure it was a mistake. He went and sat on a hill and blankly stared into the distance. But he also had moments of anger that broke through his confusion.

In Dec. 2019, just before Kellen’s death, Matt finished his contract in the Marine Corps. He had just moved back to San Diego and was planning to live with Kellen and another cousin. The three of them had been extremely close as children. Kellen and Matt, however, had drifted apart during their overlapping tours in the military.

So much so that Matt isn’t sure whether Kellen knew that he too tried to take his own life while serving.

Matt had been having trouble with his mom, who has substance abuse problems. His mom was angry he wouldn’t give her money and said unforgivable things to him. He wondered what the point of being alive was in a world where his mother didn’t love him. In a drunken state on Cinco de Mayo, while he was stationed in Georgia, he went home and tried to drink household cleaners.

“It was less than a minute of thinking and with all that alcohol in my body that’s all it took,” he said.

Matt immediately regretted his decision. He thought of his dad and everyone who would miss him. He didn’t want them to carry his death around.

Photos by Miranda Alam for Voice of San Diego

“I crawled out to the hallway. I was foaming at the mouth. I banged on my buddy’s door,” Matt said. “Luckily, he was home and he opened the door. Immediately he took me to the hospital, speeding through lights and everything.”

Kellen, who had also been doing sustained drinking before he killed himself, never heard that story from his cousin’s mouth.

Talking about suicide is taboo in every part of American life, not just the military. And that taboo deepens people’s sense of isolation at a time when they feel death is the best possible choice for themselves.

“We need to make suicide not a taboo word,” said Matt. “The best thing I think you can do is be direct with people. In the military they say if you’re worried about someone you should ask them directly if they’re planning to kill themselves. Because if you tiptoe around it, it can seem like you’re not taking it seriously.”

If you or someone you know might be considering suicide, please call: 800-273-8255.

This story was completed with assistance from the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism.

Correction: This story previously misstated Michael Soesbee’s rank. He was a Lance Corporal.

[This story was originally published by Voice Of San Diego.]