Diabetes

by Don Finley

I began covering medicine in 1987 when AIDS was the biggest and most compelling national health story out there. Naturally, I thought I'd be spending most of my time writing about AIDS. I was wrong. As I made the rounds, talking to doctors, hospital administrators and public health workers in my community, they told me the same thing: AIDS is pretty bad, but diabetes is killing us.

Mexican-Americans would soon make up a majority in San Antonio. And like a canary in the coal mine, the city offered up an early glimpse at the global epidemic we see today.

The rise in obesity, which is linked to the rise in diabetes, gets most of the attention these days. Obesity is visible - walk down the street and you bump into it. Obesity runs counter to our sex- and celebrity-saturated culture. It is still possible to be taken aback by the sight of obese people, particularly after four and a half hours of watching actors with body fat percentages in the single digits parade across our TVs (four and a half hours being the average daily viewing dose per American, and one of the likely causes of obesity.) A tiny voice in our heads tells us that they could lose that weight if they chose to do so - even if we know better, even if we've struggled to lose a few pounds ourselves.

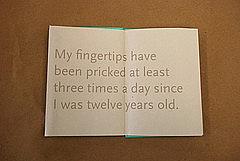

Diabetes, on the other hand, is silent and tragic. Type 2 diabetes, which accounts for more than 90 percent of cases, has few high-profile advocates (B.B. King is one). A sizable proportion of diabetics are poor, elderly, undereducated, or members of racial or ethnic minority groups who are struggling with an incredibly complex disease that puts most of the management burden on the patient, rather than the doctor. You'll find, unfortunately, few support groups for Type 2 diabetics. Although many diabetics are obese, some (many Japanese-Americans, for example) are not - which is why I think diabetes deserves more attention than it gets, separate from obesity and its cultural baggage.

Some benefit by lumping heavy and obese categories

Data concerning people who are overweight and those who are obese get lumped together as well - particularly by public health officials and obesity professionals who have their own reasons - financial or otherwise - for including two-thirds of Americans among the unwell. But there is controversy over lumping them together.

Katherine Flegal, a researcher with the National Center for Health Statistics, created a stir by calculating that overweight (but not obese) people had the lowest overall risk of dying from any cause. The fat-but-fit debate, over whether overweight people can be physically active and healthy, is unresolved.

Researchers, such as Dr. Steven Blair, professor of public health at the University of South Carolina, say physical inactivity is the true culprit, and in fact obesity and inactivity are hard to separate. Obesity is associated with a host of serious health problems, including heart disease and stroke; cancers of the breast, endometrium, colon, kidney and esophagus; osteoarthritis; sleep apnea; gallbladder disease; high blood pressure, cholesterol - and, of course, diabetes.

A height-weight formula called the Body Mass Index is used to determine whether someone is overweight or obese. A BMI of 18.5 to 24.9 is considered a normal, healthy weight range; 25 to 29.9 is overweight; 30 and above is obese, according to the U.S. government. A BMI below 18.5 is considered underweight. Like everything else about weight, the use of BMI to group people into categories has been controversial. It has been criticized as a blunt instrument that doesn't take into account differences in muscle mass, among other things. While it's possible to calculate BMI using a No. 2 pencil and the back of an envelope, most of us are content to use an online BMI calculator, found on the CDC's Web site and elsewhere on the Web.

CDC data help to quantify the problem

Nationwide, about 34 percent of adults are considered obese, according to the most recent National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). Those rates have more than doubled from 15 percent in the late 1970s; they rose fairly steadily before leveling off. Women have slightly higher obesity rates than men, and there are wider differences among racial and ethnic groups - with some of the highest rates among African-American and Latina women. Much alarm has been sounded about the rising rates of overweight children. Weight concerns are calculated differently for children, based on their ages and height and weight percentiles.

In the past few years, the CDC has made available county and metro area rates for diabetes, obesity, physical activity and nutrition, updated yearly and highly useful for reporters. The Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System is a telephone survey run by state health departments and conducted each year. Unlike NHANES, which includes physical examinations, the risk factor survey relies solely on self-reported information. Probably the most reliable question of the bunch is: "Have you ever been told by a doctor that you have diabetes?" While answers to questions about obesity, physical activity and food intake should be taken with a grain of salt (people tend to fudge their heights and weights, and few remember accurately what they ate recently or how much they exercise), the answer to the question about whether a doctor has delivered some bad news doesn't come with a lot of wiggle room. And that's only diagnosed diabetes. The CDC estimates that 25 percent of diabetics are undiagnosed.

In the summer of 2008, the CDC updated its estimates for diabetes to include nearly 24 million Americans - about 8 percent of the population. More than twice that many, or 57 million, suffer from "prediabetes" or impaired glucose tolerance.

A "public health train wreck"

Diabetes advocates have been pushing the term "prediabetes" because they want these folks to take the condition seriously. Prediabetics have higher than normal blood sugar, but not as high as full-blown diabetics. As many as three-quarters of prediabetics will go on to develop diabetes. Some doctors think that many of these prediabetics are actually diabetic - that the baseline for diagnosing diabetes is too high. Studies have shown that some prediabetics already are suffering eye and kidney damage.

If you add up those two groups (diabetics and prediabetics), you're talking about a quarter of the U.S. population. That's a stunning number of people and a big story by any measure. And, given the huge health costs associated with diabetes - retinopathy, cardiac and stroke care, peripheral neuropathy and amputation, gallbladder disease, ovarian cysts, depression, impotence (the list goes on and on) - it's a public health train wreck.

Type 2 diabetes, by far the most common form, has been called a disease of civilization. Unlike Type 1, in which the pancreas can't produce insulin, Type 2 diabetics make plenty of insulin - at least for a while. They are insulin resistant, which causes beta cells in the pancreas to respond by producing more and more insulin - until they finally stop working and the patient requires insulin injections.

Around the world, rising rates of obesity and diabetes have followed affluence - richer, cheaper and more abundant food, cars, computers and a steep and steady decline in strenuous work. At some point, however, like a bell curve, diabetes moves down the economic and social ladder as a country reaches a certain level of prosperity. Barry Popkin at the University of North Carolina describes the phenomenon as the "nutrition transition" in which the rich adapt and the poor suffer.

Doubt about strict control of blood sugar levels

In diabetes, some issues seem to keep coming back like bad pennies. Since the discovery of insulin, doctors have debated the benefits of tightly controlling blood sugar. The big story in diabetes in 2008 resulted from two large trials that found no benefit from aggressively lowering hemoglobin A1C levels - an indicator of long-term blood sugar control - below the recommended 7 mg/dL in patients at higher risk for heart disease. One of those studies, the Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes study, known as ACCORD, found a 22 percent higher risk of death among those who tried to maintain A1Cs below 6. Another study found no increased risk or benefit in regard to mortality. Those studies were discussed and dissected at the 2008 American Diabetes Association scientific sessions in San Francisco.

At that same meeting, Dr. Ralph DeFronzo of the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio proposed a powerful three-drug cocktail for most newly diagnosed diabetics, which he said would preserve what insulin production they still had. A head-to-head study comparing that regimen with standard treatment - which generally involves trying one medicine at a time, often until each stops being effective - has been approved for funding.

Some doctors and public health advocates lay at least part of the blame for poor diabetes management on the health care system. With its emphasis on procedures rather than primary care skills, the reimbursement system makes it hard for doctors, nutritionists and educators to give diabetics the continuing help they need to avoid complications and stay healthy. The chronic care model, developed by Dr. Ed Wagner and colleagues, has specific recommendations for physician practices, and is being promoted by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and others. Most of the presidential candidates who offered health reform proposals this year gave at least lip service to putting a greater emphasis on chronic diseases such as diabetes.

But what about managing obesity, the root cause of much of that diabetes? If treating obesity were easy - well, we wouldn't see much of it. The demand for fuel - like reproduction - is imprinted on every cell by millions of years of evolution. The idea is that people have a kind of thermostat that adjusts appetite to maintain a constant reserve of energy in the form of body fat. Researchers call it a setpoint or settling point, and believe our rich diets and inactive lifestyles are moving the needle upward on the thermostat. Some people are more susceptible than others; about 40 to 70 percent of the variation in obesity is thought to be caused by genes. But it's a fat-happy environment of cheap calories and inactivity driving it all.

Chances are slim for long-term weight loss

And so while people can lose weight on any number of diets, long-term success is bleak. It can be done, however. The National Weight Control Registry studies about 5,000 so-called successful losers - people who have shed at least 30 pounds and kept it off for several years. They tend to eat a low-calorie, low-fat diet, and burn almost 2,800 calories a week in exercise - the equivalent of walking about four miles a day. The registry has some limitations. The vast majority of its successful losers, for example, are Caucasian.

Weight loss surgery, once a fairly radical approach, has become commonplace, with studies showing it can prevent and even reverse diabetes in many patients. It carries risks, particularly gastric bypass surgery.

A national debate is under way on how best to prevent obesity and diabetes, particularly in children. Unfortunately, there's not a lot of good evidence for any particular strategy. Nonetheless, communities across the country are wrestling with the need to eliminate junk food in schools, increase physical education and limit TV viewing and computer games.

In adults, the Diabetes Prevention Program showed that intense lifestyle changes worked better than drugs in preventing prediabetics from developing full-blown diabetes. Those lifestyle changes required a lot of counseling and handholding, and studies are under way to find an economically feasible version to use across the country. And there are doctors even giving some of the newer line drugs, like Actos, to prediabetics. A consensus statement issued in August 2008 by the American College of Endocrinology called for a clinical outcomes study that would "test the hypothesis that simultaneous use of intensive lifestyle modification, plus preventive pharmacotherapy, would result in the greatest degree of diabetes prevention in prediabetic subjects."

Legal issues: discrimination and registries

Like blood sugar control, discrimination against diabetics is another area that keeps resurfacing. A recent landmark case involved a San Antonio police officer, Jeff Kapche, who successfully sued the department in federal court after he was blocked from promotion because of his diabetes. Advocates fearing discrimination have been the loudest opponents of diabetes registries, which New York City recently implemented and San Antonio is in the process of doing. Laboratories report A1C test results to public health officials, who can analyze what patients have out-of-control blood sugars and notify both patient and doctor.

Believe it or not, I've barely scratched the surface of the topic. Reporters have no shortage of angles, economic consequences, ripple effects and theories to explore - some of them fairly strange (viruses, corn oil, diet soft drinks). In recent weeks, working on the fourth and probably final series of my career on this topic, I've been struck by just how overwhelmed primary care doctors are in my community. Some say diabetics make up 60 percent or more of their practices. How quickly do they write off their equally overwhelmed and exhausted patients as non-compliant? How does the health care system reach and motivate this large army of diabetics? I don't know yet, but I'm convinced it's a pretty good story.

Don Finley is the medical writer for the San Antonio Express-News and was a 2008 California Endowment Health Journalism Fellow. His fellowship project on diabetes in San Antonio can be found here.