How letting sources lead transformed my reporting on survivors of sexual assault

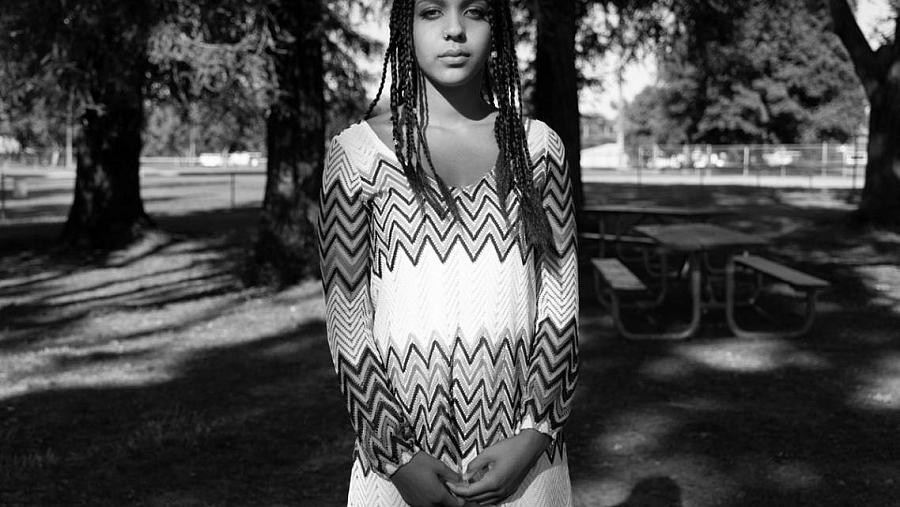

Sexual assault survivor Dominique Green joined a “cohort” of survivors who helped inform and shape CapRadio’s reporting on the issue.

Andrew Nixon/CapRadio

Building trust takes time. It takes attention to detail. It takes acknowledging that what we consider the traditional journalistic process does not work well for those who’ve been repeatedly betrayed by people they thought had their best interests in mind.

This is something I learned over the past year while reporting on survivors of sexual assault, and it’s completely changed the way I do my job.

The project began with a call from a CapRadio listener who wanted her story told. Her attempts to report a rape to Sacramento police yielded no justice, and she said the experience left her feeling powerless, lost and enraged.

When I met her for a first interview, she was clear: This was her story, and she wanted some agency in its telling.

This is not how things typically go. Usually reporters do interviews and spend time with subjects, and then disappear for a while to write. We come back weeks or months later with a published piece, often with little to no input from the people at the center of the narrative.

With leadership from CapRadio’s senior community engagement strategist, jesikah maria ross, our team is shifting that dynamic. We made a decision early on to believe survivors, knowing from research and expert interviews that false rape reporting is rare. And we decided that due to the sensitivity of the topic, we needed help from people with firsthand experience to get the story right.

Figuring out what that should look like took some deep thought. First, I used our original caller and some other contacts in Sacramento’s sexual assault support circles to reach out to as many survivors as I could find, with a special ear for those who had reported their crimes to police and hit a dead end. I met eight women, individually at first and off the record. I tried to explain our goal — to publish explanatory journalism that helps bridge the gap between law enforcement and rape survivors. I asked them whether they’d be interested in joining a “cohort” of survivors who would help shape the project — they all said yes.

Before the first cohort meeting at the station, we put a lot of effort into creating an environment that made survivors feel cared for. This included healthy snacks and drinks, candles, Kleenex tissues and little crafts for people to play with in case they became nervous or fidgety. We also secured the help of a counselor from the local rape crisis center to be on hand in case anyone needed immediate support.

At first, getting everyone together was a little tense. I was nervous, as were many of the survivors. jesikah and data reporter Emily Zentner and I were patient. We gave survivors space to breathe, and allowed them to tell their stories at their own pace, tell selective parts of their stories or simply listen. We ended every session with a soft transition back to the real world, such as a meditative exercise or a relevant quote or reading (often brought to the table by cohort members). All of these elements were requested and established by the members under a “group agreement” that we wrote down at the beginning of the process.

We started to meet biweekly, and then monthly. Over time the cohort members developed a rapport among themselves. They naturally moderated the conversations and did not jump on one another’s words. When one member shared something difficult or became noticeably upset, cohort members instinctively showered her with support. Most of these women had been dealing with their trauma alone for many months. We hoped to offer them a place to find community, where the common denominator didn’t need explaining.

We invited participants to weigh in on every aspect of the project — what to name it, what should be in it, questions we should ask experts — and this gave them a sense of agency and ownership, not just of their own stories but of the whole reporting project. Several of them have told us, on more than one occasion, that being part of the CapRadio project gives them a sense of purpose they were struggling to find.

Survivor Erin Price-Dickerson said being part of CapRadio’s reporting has given her more courage to speak up about her experiences.

“I feel like you guys took the extra mile and the extra step to help me. Like, you know what? OK, if they can pursue this stuff and they’re trying to get the message out there, I don't need to be scared ... You know, you can maybe help one person, but at least you're helping somebody besides staying quiet and then harboring all of this.”

This requires a careful balancing act from the journalist. Throughout the many months that I’ve been working with these women, I’ve found myself playing a role that goes beyond documentarian. As I’ve learned about their experiences, I’ve found myself invested in their healing journeys, and in the healing journeys of future survivors. This is a line we don’t normally cross in journalism. Caring about your sources has historically been considered a big no-no. But the nature of this work is different. You have to be invested in their well-being to build this kind of trust. You’re still not taking sides on the issue at hand, and when you’re making statements about problems with the system you still need to let the other parties weigh in. But it’s possible to both treat sources as human beings (and hope for better outcomes for them) while also holding to account the system they say is causing them harm.

The deep engagement we undertook with these survivors is enriching my journalism in several ways. Once the cohort dynamic was established and we had a mutual understanding of roles and goals, we began recording group conversations with the survivors about a different topic every two weeks, such as misconceptions about rape, dating after an assault, and the effects of trauma on memory. The tape we came out with was steeped in raw emotion, yet still conversational and accessible. The women built on one another as they addressed the topics at hand, bringing in anecdotes and perspectives that give outsiders an important glimpse into their worlds. As a journalist, I felt I had an unprecedented level of access into people’s experiences. This will allow me to craft a deeply reported project that draws people in and puts them ‘in survivors’ shoes in a way that most published media on assault rarely does.

Even when the microphones weren’t on, every conversation we had in our station’s community room, and the many Zoom conversations we’ve had since then, informs my reporting and writing on this project. These careful steps — talking to the survivors, looking at their crime reports, getting the step-by-step breakdown of how they recall their interactions with police —gives me the information I need to ask targeted questions of law enforcement and expert sources. It also helps me build a foundational knowledge of sexual trauma, which allows me to write more sensitively and accurately.

The July miniseries on assault survivors and police reform is a perfect example of how the engagement work translated to powerful, community-informed journalism. At our June cohort gathering, as social justice demonstrations around George Floyd’s death continued in Sacramento’s streets, I asked the cohort members a question: “What does ‘defund the police’ mean to you as a survivor?”

Their answers were varied, and fascinating. They rehashed some of their critiques of law enforcement handling of rape reports, but then they started to drum up solutions. What if trauma-informed counselors were the first to meet a survivor in the aftermath of an assault instead of uniformed officers? What if law enforcement agencies acknowledged that distrust of police in Black and brown communities keeps reporting rates among survivors of color extremely low? What if money currently used on police equipment were shifted toward safe houses? Or helped to fund faster rape kit processing?

I took feverish notes during that meeting. Then I started to do research. I found blog posts from survivors all over the country, especially Black survivors, who were catapulting from George Floyd’s killing into a much bigger question about not just how police should be handling rape cases, but whether they should be handling them at all. I found two local survivors who were active in the Black Lives Matter and defund the police movements. Combined with two members of our original cohort, these sources gave the project an intersectionality — between race, rape culture and policing — that it previously lacked.

And because I had months and months of background on sexual assault, the reporting and writing flowed with ease. I produced three audio features and an enterprise text article in less than a month. Despite the deadlines, I followed the same careful steps while interviewing these survivors as I did in the cohort meetings — make them comfortable, be patient, give them space to tell it their way.

Once I started writing, I stayed dedicated to keeping survivors in the loop. The last thing I wanted was to surprise someone or misrepresent their experiences in a way that might re- traumatize them. So instead of the normal fact-checking process (names, dates, places) I called each survivor and walked them through the parts of their story I used, and how. If I summarized something from an interview, I read it back to them to make sure it rang true.

I can think of one poignant example of where this made a difference. After listening back to one survivors’ comments about the days following her rape, I wrote in my draft that she was “depressed” in the immediate aftermath. When I read this back to her she asked me to pause.

She thought for a moment. And then she said, “I wasn’t depressed. I was debilitated.”

She then brought up details about what those hours were like, such as her inability to get off of the floor and pour a cup of coffee or make herself breakfast. I made the changes, and the story came out better for it.

Survivors’ voices make up the backbone of this work. If I were to be the sole determiner of how their experiences got conveyed to the public, I would be taking away their power in a way not so different from the law enforcement agencies who they feel betrayed their trust. Instead, I’ve learned that mutual understanding and shared goals can lead to collaborative yet balanced work. It’s a lesson I plan to carry forward anytime I cover trauma.

Here are some basic tips I’ve picked up from working with survivors:

● Give it time. This is not the kind of work that can be done in a month or even in a year. Scheduling can be especially hard. Sometimes survivors will be late to a meeting, or need to reschedule because they’re having a really challenging day. Always let them set the time and place, and don’t get upset if they change the plan.

● Partner with a support person. Gatherings or even interviews can be emotionally taxing on survivors. Ask a counselor from your local rape crisis center to be present while you do the work, so that if someone needs to take a break they can do so with a professional.

● Don’t change the plan on them. If they’ve set aside time to talk to you, they’ve probably spent some mental energy preparing for it. Try not to let them down if you’ve already made a commitment.

● Ask what to ask. Survivors helped me craft many of the questions I’ve been asking experts. They know where the breaks in the system are because they’ve been there.

● Find out what they need. Some survivors want to tell their stories without interruption. Others need specific questions to prompt them. Trauma can affect memory in a way that makes it difficult for them to focus. Ask which interview style the survivor would prefer.

● Request data early. Law enforcement agencies don’t want to give you their numbers and they will drag their feet.

● Give updates. Tell survivors what you’re up to, whether it’s an interview you’ve conducted or a public records act request you’ve filed. It creates a sense that you’re following through, and educates them about the journalistic process.

● Be transparent. Don’t make promises you can’t keep. If you’re hitting a snag or the story is on pause, tell your sources the truth. Ask them to trust you, and give them whatever support they need through the process.

And here’s what survivors say they would like to happen while working with journalists:

● Be careful about your first question. Survivor Jesa David says she once did an interview that started with a judgmental, invasive question.

“The first question she asked me was clearly to elicit a big reaction, to make me cry maybe … That wanting me to be taken off my guard, it just felt a little bit predatory … I feel like the way that you guys are so careful with us and so very much invested in having our consent in every step of the way and everything that you do. It just means so much to me in creating this environment where we can be open and safe — with journalists, which is a big deal.”

● Restructure the power dynamic. Penny, a survivor who asked us to omit her full name for safety reasons, said there’s a problem with the way reporters traditionally treat sources.

“The journalist approaches them like a natural resource and it's their job to turn that natural resource into something else by adding value. They sort of do their magic and turn the source into something else. But instead of that perspective … they can be thought of [as] already having all of the value inherent within them. And it's just that they need someone to provide the conduit to make that value evident. So it's just like the words are there and the journalist just needs to put the megaphone in front of that person so that they can speak and be heard.

● Show that you care. One survivor, Monica Schwab, talked about feeling like CapRadio was invested in her healing journey.

“I've needed the consistent guiding light,” Schwab said. “You know, I still have my own process to go through … But to know that being in the space of consistency and, not being judged, it helps continue, like, forward motion.”