How one reporter got to the heart of California’s single-payer debate

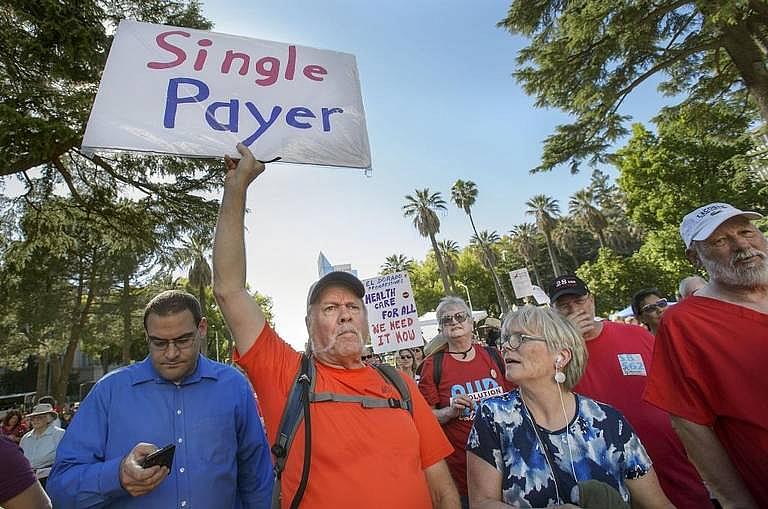

Demonstrators at a Sacramento rally last year in support of a bill to create a single-payer system in California. (Photo: Randall Benton/Sacramento Bee)

A pair of California state senators unveiled a bill in early 2017 to create a single-payer health care system for California, setting off a flurry of questions from The Sacramento Bee about how much the system would cost, how it could be accomplished and whether the authors of the bill were prepared for the political fight ahead.

Months later, the price tag was estimated at $400 billion, more than twice the state budget, and the authors had not identified a way to pay for it. There was also no strategy to secure the federal waivers needed to retain federal health care funding in California.

So we started asking questions.

It was a huge story, and other media outlets, rightfully so, jumped on it, also raising questions about its cost and political chances. But we wanted to do a deeper dive into the cost question.

How much does California currently spend on health care? How are its various programs funded? How do various populations, from the elderly to the disabled to low-income people to undocumented immigrants, get their health care today? How would that all change under single-payer?

I dove in, downloading and sorting national health expenditure data. The federal government does not break down federal health care data by state, so that was a huge challenge. I turned to nonprofits and universities that do their own analyses. Researchers at the University of California, the Kaiser Family Foundation and the California Health Care Foundation provided an important baseline from which I started to build my data set on total health spending in California.

That took about a month, and there were a lot of headaches. I merged data sets that did not marry. I also found competing data from different organizations. For example, the National Health Expenditure data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid did not merge with global data from the Organization for Cooperation and Development, which tracks spending by other countries.

A lot of data was also outdated, so I asked experts in California to run projections. At that time, the state Legislative Analyst’s Office had released their own analysis building on the same state and federal data I was compiling, and they had built a model that brought everything up to date, so that was immensely helpful. I was able to compare the work I’d done with theirs, then meet with them to find out why I had different numbers than they did. That helped me decide what to use for my analysis.

From a data perspective, the biggest thing I learned is to be OK with messy data. It’s OK if it’s doesn’t always match up. Do the best you can with the data you can compile, and go to as many sources as you can. Build different data sets, then talk to experts about what they would do. Rely on your sources to push back against what you think you know. Get out of the office as much as possible for face-to-face interviews and to show them the data set you’re working with.

That process, after getting comfortable with the data I had and identifying its shortfalls, was imperative to a critical analysis. I also kept a running list of questions in a comments field in each of the databases I used. The data I compiled was state health care spending on Medicare, Medi-Cal, employer-sponsored insurance, Obamacare subsidies and individual plans purchased through Covered California, for example.

I had broken down spending in much greater detail, for example, the programs that tie to each funding source — like the Children’s Health Insurance Program and the Medi-Cal program for undocumented minors in California. I ultimately stripped that out for the written story and data visualization elements, but I couldn’t make that decision until after I’d already done the analysis.

All the while I was compiling data, I was keeping a list of potential sources and experts to follow up with. I was reading medical journals, doing a deep background dive on health reform efforts across the United States, from Vermont to Maryland to Colorado, as well as in California. I kept a Google Doc and summarized each effort to enact universal, single-payer health care in a few paragraphs, so when it came time to writing, I’d be able to cut one out for context in my story.

At the heart of my reporting, I found that no matter how California proceeds, tremendous uncertainty exists over how a state-based single-payer system would work. Regardless of how it’s crafted, the costs would be steep, and Californians likely would face huge increases to their tax bills — both to pay for it initially and to cover inevitable cost increases in the future.

When it came time to double down on reporting, I took the data I wanted to use for my nut graf and put it in a Google Sheet so I could share it with sources to help them visualize what I was trying to get at. I also encouraged them to add their own notes or questions in a separate column.

Then I spent about two weeks on the phone interviewing people and meeting with sources. I connected with patients who could illustrate some of the problems with California’s health care system that sources had identified. Having real voices up high in my story I think helped people relate to the larger problems and deeper issues I would convey.

During the reporting process, I built an outline with the data analysis as the nut graf and the anecdotes as my entry into the story.

Then it was all about staying focused on the most important elements — the costs of the current system, and what potentially a single-payer system would cost. I wove in sections that illuminated other state and federal challenges — including political and administrative hurdles. Everything that didn’t fit, I highlighted in yellow in my documents (the system I use for material I know I’m not going to use).

The reporting process helped me break additional stories that same week and identify future political stories, as the conversation in California continues. It’s now a key issue in the campaign for California governor, so the discussion isn’t going away.

Read Angela Hart’s 2017 California Data Fellowship stories here.