Reporting with impact from the frontlines of a fatal birth defects cluster

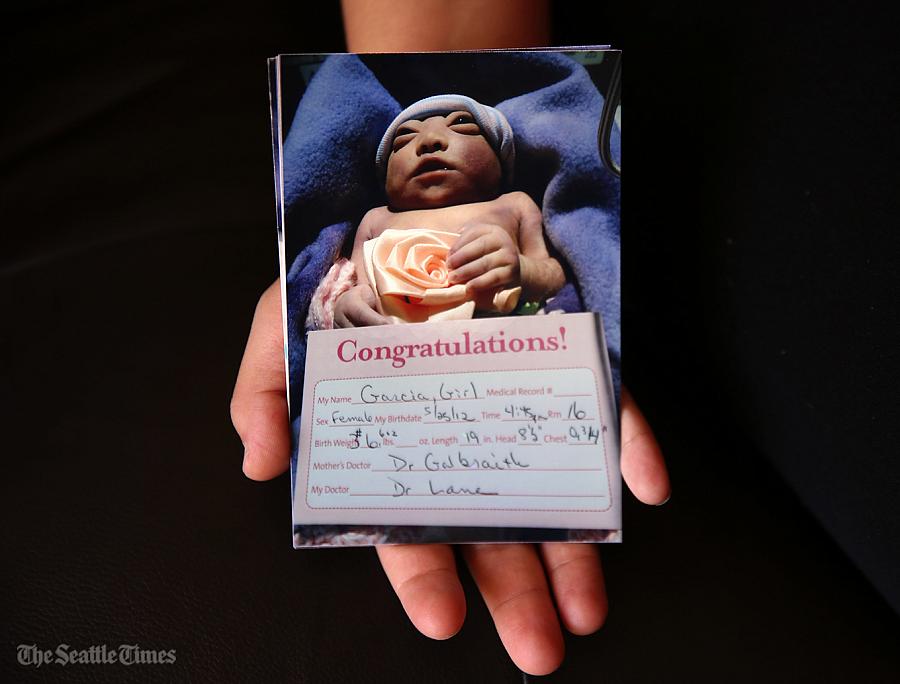

Maria Rosario Perez, who suffered a rare and fatal birth defect, died less than one hour after her birth. (Photo courtesy JoNel Aleccia/Seattle Times)

I had read the clinical reports and seen the disturbing images on social media sites dedicated to babies with anencephaly, the rare and fatal birth defect that has increased mysteriously in three rural counties in Washington state.

But only when I was sitting on Sally Garcia’s couch in her Prosser, Wash., apartment, watching as she unpacked the few souvenirs of her daughter’s 55-minute life, did I fully recognize the horror of the situation.

“She was missing her head bone and she was missing part of her brain,” Garcia said, handing me a snapshot of her tiny girl, Maria Rosario Perez, who wore a knit cap to hide the damage. “Her eyes looked different. She looked like a little frog.”

That photo, which eventually ran as the main art in our Seattle Times series, underscored what was at stake in this growing cluster, which has affected more than 40 pregnancies in the region since 2010, a rate nearly five times higher than the national average.

“These are babies, for god’s sake,” is how the whistleblower nurse who first discovered the problem put it.

Our investigation found that although Washington state health officials had launched a probe into the anencephaly rise nearly two years ago, their efforts had been anything but vigorous. Even as cases have continued to climb — another recent case has brought the total to 42 — health officials tasked with solving the mystery have missed basic chances to find answers.

They hadn’t talked to all of the women who lost babies. They hadn’t collected samples or conducted tests that could tell whether there’s a genetic or environmental link to the problem. And they hadn’t effectively informed families about how the problem might be prevented.

For us, one big hurdle to reporting this story was that it involved documenting what health officials didn’t do. No one could say they were doing nothing, but many said they weren’t doing enough. Pinning down a lack of effort meant we had to find outside experts with enough experience and authority to stand up to the leaders of the state department of health.

In addition, one of our goals in pursuing the story was not just to expose the inadequacy of efforts to inform families how to prevent the problem, but also to make up for it, in some ways. Our effort included a community engagement project that distributed more than 15,000 postcards that included information about our series, but also a broad public health message from the March of Dimes about the need to take folic acid before pregnancy, the only known way to possibly prevent anencephaly and other neural tube defects.

By systematically identifying the obstacles to progress, we were able to bring about change to help prevent future cases of anencephaly. The FDA, which we found had delayed for years in a key intervention, approved enriching tortillas with folic acid in response to the reporting. And the state changed a Medicaid rule that limited pregnant women's access to a vitamin that can help prevent the deadly disorder.

To help other reporters working on similar public health projects, here are a few lessons I learned.

- Think creatively to find real voices. Tracking down parents of babies lost to a rare and fatal defect isn’t easy. State health officials wouldn’t divulge names, of course, and clinics in the rural area where the defects occurred were suspicious of journalists and wouldn’t share our requests with patients. Instead, we turned to Washington state’s death records, where we found the names of some infants who died of anencephaly, even though many were only minutes or hours old. We found other names by requesting records from the small local funeral home where the owner had buried many of the babies who died. Finally, we talked to a sympathetic doctor who had delivered several of the babies and the doctor agreed to ask one mother, Sally Garcia, if she would share her story.

- Find the best experts that you can. Don’t just rely on the officials in your region or state for expertise. Make sure to know who in the nation — and the world — is an expert in the subject you’re pursuing and let them assess the situation. We turned to a retired scientist from the Center for Disease Control’s Birth Defects Division who spent his career studying rare defects. We also talked to the woman who is leading the world’s largest genetic study of anencephaly to ask about the efforts of Washington state officials.

- Engage new kinds of community partners. We turned to the Catholic diocese in Yakima, Wash., which oversees churches in the counties where the birth defects have occurred, to help distribute our postcards with the public health information. Because the church leaders wanted women to know about the importance of taking folic acid, they agreed to insert our postcards in church bulletins. On the weekend before Christmas, one of the busiest times of the year, they distributed more than 15,000 postcards to Anglo and Hispanic families.

- Make sure your work is seen by the people it affects. More than half of the women affected by these birth defects are Hispanic and we wanted to ensure that our stories were seen by Spanish-speaking readers. So we paid someone to translate all the stories into Spanish and then we ran those versions on our website, too. We also worked with the Spanish-language newspaper that circulates in the affected area and they ran the story, too.

- Focus on the outrage. Cluster investigations are notoriously difficult; small numbers and multiple overlapping causes make it hard to identify a “smoking gun,” the experts say. But we constantly reminded ourselves what was at stake: Growing numbers of babies born without brains and state officials who weren’t doing everything they could to find out why.

If you have any questions or comments, please feel free to contact me at jaleccia@seattletimes.com or via Twitter @JoNel_Aleccia.

Read JoNel Aleccia’s fellowship series here.