Reporting on the turning point in the hep C epidemic

2014 was a turning point for people living with chronic hepatitis C. For the first time since the discovery of the virus in 1989, there was a cure. Until recently, patients with hepatitis C had few treatment options. The standard was a medication called interferon, which had to be taken via injection a few times a week in the stomach, caused debilitating side effects, and worked less than half the time in most people. It had to be taken in combination with other drugs, just as toxic. And some people couldn’t even tolerate interferon.

Today, there are several new medications on the market that have reported cure rates of up to 95 percent or more. Doctors and patients report few if any side effects. And one of the drugs, Harvoni, requires just one pill a day.

Dr. John Ward, head of the CDC’s division of viral hepatitis, put it to me this way: “The era that we have been waiting for has finally arrived. And that era is of safe and highly effective, curative therapies for hepatitis C.”

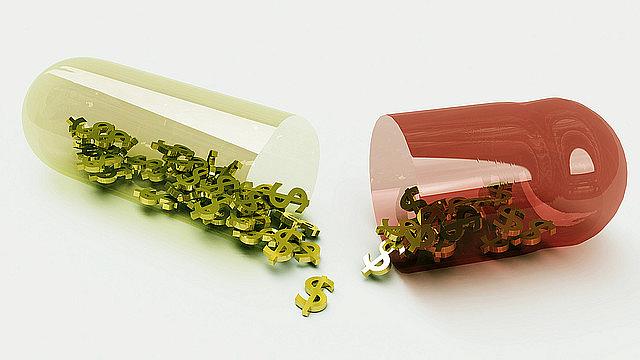

The trouble is those therapies cost upwards of $90,000 dollars for a full course. They’re so expensive many patients just can’t access them right now. While they wait, their livers are under attack. Hepatitis C is one of the leading causes of liver cancer, cirrhosis, and a host of other unpleasant symptoms arising from a badly scarred liver.

The arrival of these new drugs for hepatitis C coincides with another trend: Millions of baby boomers who contracted the disease decades ago are just now showing up in doctors’ offices and emergency rooms, sick with something most didn’t know they had. Add to that a wave of new infections, spreading among younger injection drug users — people who got hooked on opioids and then turned to heroin — and you’ve got a unique moment in the history of an epidemic.

The project

As a National Health Journalism Fellow, my project, “At the Crossroads: The Rise of Hepatitis C and the Fight to Stop It,” examined this moment. I became fascinated with the idea that so many factors surrounding an epidemic were coming to a head, right now. And I wanted to draw attention to the fact that hepatitis C affects nearly five million Americans, although funding to prevent and treat it pales in comparison to other diseases.

My series took shape as eight separate but connected radio stories. Most featured a patient dealing with this disease. I started with the broad outlines, in the stories “A Tale of Two Epidemics” and “Finding Hep C Infections Before It’s Too Late.” Then I examined the high cost of new medications and how insurers and public payers are grappling with those costs. I tried to move the discussion away from how expensive the new drugs are toward whether they’re cost effective. I’d seen lots of coverage of the prices in the media, but nothing really putting those prices in context. And finally, I focused on three populations hardest hit by hepatitis C: veterans, inmates, and people who use injection drugs.

Because of who is affected and how you contract this disease, hepatitis C is not easy to talk about. It was challenging to find patients to share their stories, and tough to find statistics, because so much is still unknown or underreported.

But I was able to connect with some fabulous researchers, doctors, and other professionals who pointed me in the right direction. I relied heavily on epidemiologists and infectious disease specialists, as well as on organizations that specialize in advocating for people in the criminal justice system and for people in recovery from addiction.

Outreach

To further extend the reach of my project, I tried several things. Admittedly, it’s difficult to be a one-woman-band – reporting, producing, marketing, promoting, etc. – but I gave it my best shot:

- Each story aired twice on Rhode Island Public Radio, and was made available to other stations via shared networks

- Each story was posted online, often with an infographic to illustrate a concept or statistic.

- I tweeted stories out, posted on Facebook (even joining a couple of hepatitis C patient and advocacy groups, who appreciated learning about the series), and created a Tumblr to widen the audience.

- Most importantly, we held a public forum, broadcast live on Rhode Island Public Radio and webcast live, in collaboration with Brown University’s School of Public Health. About 70 people attended, not bad for a snowy January night, but more than 200 tuned into the live webcast. The forum featured several expert guests as well as a patient with hepatitis C and his doctor. The patient was brave to share his story, and I think people enjoyed hearing him and his doctor interact. Afterwards, there was a lively Q&A with the audience, which included a state senator who tackles a lot of health care legislation and seemed determined to raise awareness about hepatitis C funding among his colleagues.

- I also built my own email list of about 50 people, and sent an update any time I produced a new story for the series.

I received many positive responses to the series and the public forum. But two meant the most to me.

The first was an unsolicited email from a listener who wrote to thank me for doing the series. She said her father had recently been diagnosed with hepatitis C and that it had been confusing navigating treatment with him. The stories I produced made her feel less alone. That might be the most important outcome of this project.

The other significant outcome was a spontaneous pledge from our state health department of $30,000 dollars toward more hepatitis C education and prevention. Some of the department’s infectious disease team attended the public forum and were motivated by the discussion to approach my partners in the Brown School of Public Health with funding, asking how they thought it should be spent. Usually, public health researchers have to apply for grants and beg for money. But this time, it just came knocking. And these researchers have some innovative ideas for how to spend it to prevent new infections and get more people screened for the disease.

Resources for reporters

If you’re interested in covering hepatitis C and related subjects, here are some tips and lessons learned:

- Find out if your state has a viral hepatitis prevention and treatment strategy or action plan. Compare it to what the CDC recommends.

- Ask your state’s Medicaid agency for hepatitis C statistics. They should be able to tell you at least how many people carry the diagnosis. And they should be able to share their policy for covering the new drugs. It’s a sensitive topic for them, because many state Medicaid agencies are effectively rationing treatment, approving the new medications only for the sickest patients and asking others to wait. What kinds of restrictions are on your state’s list? Are they ethical?

- Find as many patients as possible who will tell you their stories. Pre-interview them, so they’ll feel comfortable with you when you turn on your microphone or get out your notepad. Be prepared to offer anonymity if your newsroom will permit it. I managed to keep all the patients I profiled anonymous, arguing that the stigma surrounding this disease, how you get it, and the high cost of meds the public might be paying for could put the patient at risk.

- Befriend epidemiologists and health care economists. For me, they rank up there with librarians and park rangers as fonts of useful information.

- Definitely talk to doctors, including specialists and primary care physicians, about what they’re seeing. But don’t forget to talk to nurses. They might be dealing with a particular aspect of the issue that’s surprising.

- Stay on top of the latest news about hepatitis C or the subject you’re pursuing via the CDC’s resources, medical journals, Google news alerts, hashtags, and more.

I would be happy to help any reporter interested in tackling the subject. You can contact me at kespeland AT gmail DOT com.

Photo by Bill Brooks via Flickr.