William Heisel

Contributing Editor

Contributing Editor

I have reported on health for most of my career. My work as an investigative reporter at the Los Angeles Times and the Orange County Register exposed problems with the fertility industry, the trade in human body parts and the use of illegal drugs in sports. I helped create a first-of-its-kind report card judging hospitals on a wide array of measures for a story that was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize. I was one of the lead reporters on a series of stories about lead in candy, a series that also was a finalist for the Pulitzer.For the Center for Health Journalism (previously known as Reporting on Health), I have written about investigative health reporting and occasionally broke news on my column, Antidote. I also was the project editor on the Just One Breath collaborative reporting series. These days, for the University of Washington, I now work as the Executive Director for Insitutue for Health Metrics and Evaluation's Client Services, a social enterprise. You can follow me on Twitter @wheisel.

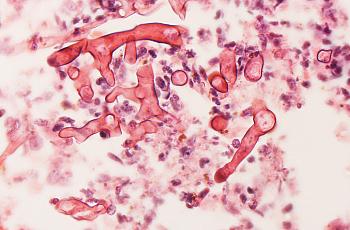

Children's Hospital New Orleans failed to disclose a serious pattern of fungal infections. That's a shame, as anything that adds to the suffering of patients should be promptly explained. It would've also let parents of the children know they weren't alone during a difficult time.

At least five children died after contracting a fungus at Children's Hospital New Orleans. The hospital kept the pattern of infections secret for five years, spurring outrage. The incident raises the question, What benefits would a full disclosure have brought?

New research proves for the first time that the fungus that causes valley fever is living in Washington state, far outside its traditional boundaries in the Southwest U.S. and Mexico. While the findings aren't cause for panic, the news suggests clinicians should be on the watch for symptoms.

Outrage followed news that at least five children died after contracting a fungal infection at the hospital. The hospital didn't tell the parents that other children had died of the same cause. Should they have?

Indiana's Vanderburgh County has stopped providing causes of death on death certificates. The local paper and a committed reader are now taking the fight to the Indiana Supreme Court, arguing that the information has vital implications for public health.

When Gary Schwitzer recently announced funding had run out for Health News Review, it caused considerable angst among health reporters. Here's a look back at some key lessons that have emerged from Schwitzer's enterprise, which has made health journalism better.

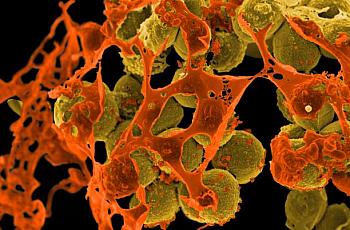

In an alarming case, two Danish journalists are facing criminal charges from the Danish government for their reporting on MRSA bacteria. When journalists aren’t allowed to report on the sources of infectious diseases, they’re kept from one of their most vital roles.

The University of Kentucky sued a reporter seeking surgical death rates and has steadfastly fought against their release, wasting time, money and reputations. Parents still aren’t any closer to understanding if their children were worse off at the hospital than elsewhere.

A new study finds the average home is a prime reservoir of drug-resistant bacteria MRSA. For reporters, the study opens up a new set of story ideas while providing a fresh opportunity to think about how we write about such infections.

The U.S. is way behind in switching to a more expansive system of diagnostic and procedure codes, which are far better at tracking diseases. Even worse, the rest of the world will switch to a newer medical coding system less than two years after the U.S. finally adopts ICD-10 in October 2015.