How prison disproportionately hurts the health of minority children

The idea that locking up parents can have baleful effects on their children’s health isn’t exactly new. I have written before about research that found links between the incarceration of parents and learning disabilities, developmental delays and behavior problems, even after other variables were taken into account.

But a new paper published Thursday in the British journal The Lancet makes clear just how unequal the effects of incarceration can be on families in the United States, which incarcerates more of its citizens than any other country.

“The emerging literature on the family and community effects of mass incarceration points to negative health impacts on the female partners and children of incarcerated men, and raises concerns that excessive incarceration could harm entire communities and thus might partly underlie health disparities both in the U.S.A. and between the U.S.A. and other developed countries,” write Christopher Wildeman, a sociologist at Cornell University, and Emily Wang, a professor of medicine at Yale.

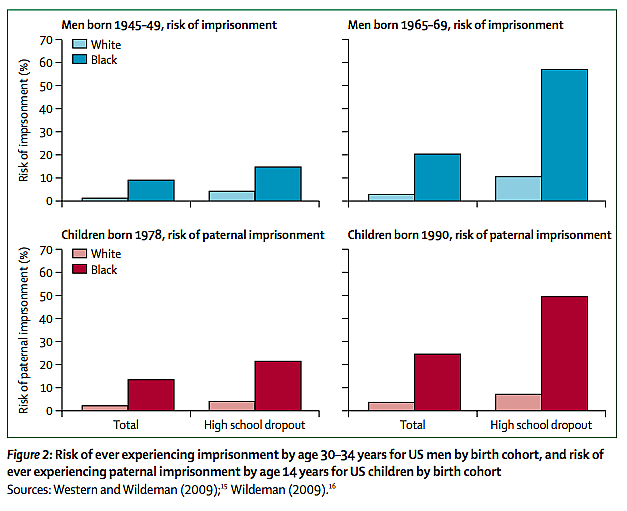

For a better sense of the disparities to which they’re referring, take a look at these basic graphs from The Lancet:

There’s a lot worthy of further exploration here, but let’s just focus for the moment on the children’s risk of having a father in prison. A black child born in 1990 had about a one in four chance of having his or her dad imprisoned, while for white children, the risk was less than one in 20.

The numbers are even more astounding when the father’s education level is factored in: For children born in 1990 to fathers who didn’t finish high school, 50 percent had dads sent to prison. For white kids in the same situation, fewer than 10 percent had their fathers imprisoned.

The disparities have clearly worsened over time as well — a black child born in 1978 to a father who was a high-school dropout only had about a 20 percent chance of the father going to prison, much lower than the 50 percent chance the black child born in 1990 had.

Such huge disparities are worrying enough on their own, and only more so when the growing body of research on the health effects on children is taken into account. After reviewing a number of studies on parental incarceration published in recent years, Wildeman and Wang write:

These study findings tell a consistent story: paternal incarceration is associated with behavioral and mental health problems throughout childhood, and a host of poor outcomes (including increased prevalence of substance misuse) in adolescence and adulthood. The most wide-ranging assessment of the effect of parental — mostly paternal — incarceration used data from the National Survey of Children’s Health, showing links to a host of negative health outcomes among children, including self-rated health, depression, anxiety, asthma and obesity.

The general pattern is clear: When families and communities lose their fathers to prison, the stress and trauma of the losses become manifest in their children’s health. One doesn’t need to get lost in apportioning blame for such unequal rates of imprisonment to appreciate the fact that this is one way in which social disparities become health disparities, passed down from one generation to the next.

While some might take solace in the fact that the U.S. prison population has fallen to its lowest level since 2005, studies like these remind us that the need to shield kids from the long shadow of their father’s sentences hasn’t lost any urgency.

[Photo by Tiago Ramos via Flickr.]