Part IV: An eviction is forever: How the legal, financial and emotional costs can persist for years

The story was originally published in CT Mirror with the support from USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2022 National Fellowship and the Kristy Hammam Fund for Health Journalism.

Carmen Diaz cleans her 9-year-old son’s room in Hamden. YEHYUN KIM / CT MIRROR

YEHYUN KIM / CT MIRROR

Click here to read the story in Spanish

Carmen Diaz remembers what it was like to be forced out of her home — to be a 13- or 14-year-old who had to pack up her room and stay at a family friend’s house, unsure of where her family would go next.

Her family had already uprooted their lives and moved to Connecticut from Puerto Rico when Carmen was 7. Her parents separated when she was young, and she lived most often with her mom, who she says got her family through hard times.

“It was hard, because we were always with mom,” Carmen said of the eviction. “She was always a very hard worker. And she always tried to do everything for us as much as she can.”

So when Carmen faced eviction years later as an adult, that memory was on her mind. She remembered that her mother never got her deposit back after the eviction, which set their family back financially. They were evicted, she said, after the owner’s home was foreclosed on, not because her mother missed rent.

She worried that her sons would have a similar memory that stuck with them over the years and be left with anxiety about where they would live.

“I know it’s hard, because I’ve been through the same thing,” Carmen said. “And I’ve gotten so stressed out and frustrated.”

Her landlord filed an eviction order against her in August for nonpayment of rent. She’d lost income during the pandemic, she said, and had reached out to him about it. Carmen owns a small home health care business that employs about seven people.

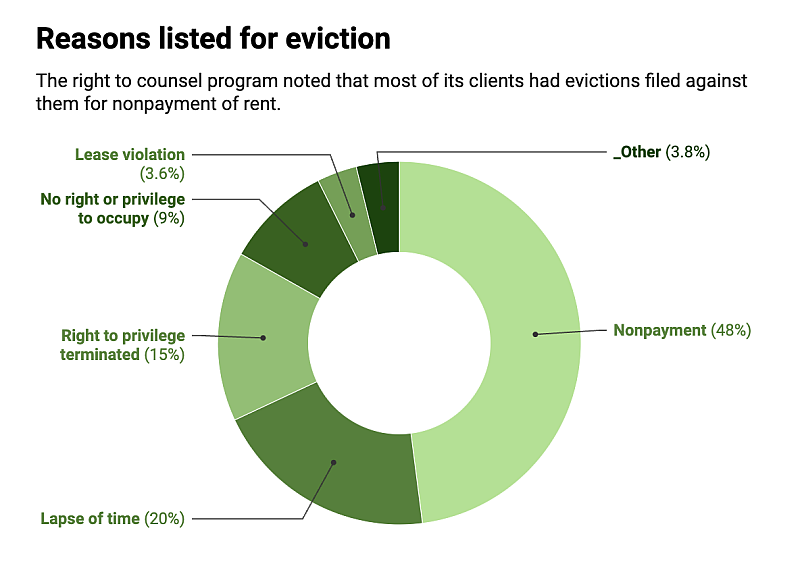

Chart: Ginny Monk / CT Mirror

Her three sons are 20, 13 and 9. The 13-year-old had the hardest time with the eviction. He’s on the autism spectrum and struggles when his routines are disrupted, she said.

He's been in the house for about seven years; it's the home he grew up in. He told his mother that when he grows up, he wants to buy the house so they can live there again, Carmen said.

After they were evicted, her boys at first stayed with their dads or with other family while she packed up the house and moved everything into storage. She remained at the empty apartment for weeks before a judge’s order overturned the initial ruling to evict.

Those weeks will have a long-term impact on them all.

Evictions can have lasting effects on tenants’ ability to find a new apartment, but they leave other scars that, for many, last a lifetime. They can lead to deep emotional wounds, including long-term mental health concerns, disrupted routines for kids and the loss of friends and community. The trauma can be profound.

“You’re talking about a lot of kids who are facing that uncertainty and instability, and you throw that on top of what the last two years have been like for a lot of kids out there, and that's a lot,” said Peter Hepburn, a researcher at Princeton’s Eviction Lab. “It’s going to have some real, lasting consequences for those families and those children.”

In interviews with The Connecticut Mirror, people who had been evicted reported long-term fears over housing instability, difficulty unpacking boxes in new places and persistent problems finding landlords who will rent to them with the eviction on their records.

Evictions can have long-term consequences outside of housing, too, experts said.

Carmen Diaz gets ready to leave for work after cleaning her sons' rooms. Carmen and her sons moved out and back into the house after her landlord filed an eviction against her. She worries about the long-term effects of repeated moves on her sons. YEHYUN KIM / CT MIRROR

Carmen, who still bears the emotional scars from her childhood eviction, had a New Haven Legal Assistance attorney working on her case. In a court filing, the attorney asked the judge to halt the eviction because Carmen has a housing choice voucher that pays part of her rent. This means her eviction was covered under the federal Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act.

The act says that the owners of certain properties, including those with housing choice vouchers, must give tenants 30 days to vacate the premises. The landlord didn’t include information about the voucher in the eviction filing, according to court documents.

Mental Health

Carmen and her family were back in their apartment by Thanksgiving, but the effects of the stressful months linger. They’re looking for a new place but aren’t sure when they’ll find something they can afford, because Connecticut’s housing market is tight.

“They don't have their daily routine, they don't have their beds,” Carmen said. “They're transitioning from moving out. And then now we have to move back. And then possibly move out again, in a couple of months.”

After life disruptions from COVID, Carmen worries about the long-term effects of repeated changes in routines for her boys, especially her 13-year-old.

Carmen said she was anxious and stressed during her separation from her children.

This is the second time a landlord has tried to evict her, although she won the first case, she said.

After her previous experiences with eviction, she’s vigilant about keeping records.

“Get documentation,” she said. “Texts, emails … you should email your landlord or send a certified [letter] to your landlord for anything. Use money orders.”

Her housing problems have dragged on. After she was able to move back in, the landlord told her again that she needed to move out or risk another eviction filing, which would make it harder still for her to find another apartment.

He told her he wants to sell the house and is offering her $3,000 to move out by the end of February.

That money wouldn't cover moving costs, she said. She’s trying to save up for a deposit on a new place and Christmas gifts for her kids — expenses that are all occurring before the end of February.

And it's tough to find a new place with the eviction on her record, she said.

"Now other landlords don't want to rent to me because of that record," she said.

Long-term stress, like Carmen’s, can hurt physical and mental health. It has been tied to clogged arteries, high blood pressure and changes to the brain that can exacerbate anxiety and depression.

“Loss is part of this,” said Christine Nucci, a therapist in Deep River. “Every time a family has to pack up … they lose a sense of attachment to anything. It works its way into evolving into a complex trauma.”

A photo of Carmen Diaz and her boyfriend is on her Christmas tree along with other family photos. Carmen loves the Christmas season and usually decorates her whole house. "But this year, what am I going to do with it all?" she said. Her family has to move out of the house by the end of February.

A teddy bear that her son gave her this year is displayed in her bedroom

Eviction filings

In addition to the lasting trauma from past evictions, other tenants interviewed for this story said their names had been attached to evictions at their parents’ homes, which made it hard to find a place to live for years after. For tenants, this often means they have to rent anywhere a landlord will accept them, which can push them into worse living conditions.

“In this post-pandemic world, where things are so tight for so many reasons, in terms of our overall housing situation, people's eviction records have become even more of a barrier,” said Giovanna Shay, litigation and advocacy director at Greater Hartford Legal Aid. “We absolutely are hearing from folks that they are being declined apartments or declined housing, because … there's an eviction on their record.

“And that could even just mean there was an eviction filing on their record, it doesn't necessarily mean there was a judgment against them.”

John Souza, president of the Connecticut Coalition of Property Owners, said he’s now less likely to grant leeway to tenants because a program that guarantees legal representation in eviction cases to qualifying renters has slowed down eviction proceedings in many cases.

Previously, evictions took “45 days like clockwork,” Souza said. Now, they’re taking closer to 85 days, meaning legal fees for landlords go up, and renting to someone with a history of eviction is riskier, he said.

“Why risk taking somebody [with an eviction], especially when there’s other people out there?" Souza said. "People keep sticking it to me. I try to help people, and I keep getting screwed. So over the last couple years, I’ve definitely raised my standards.”

He said one solution might be to give housing mediators at court more power rather than give tenants legal representation.

“Give the housing specialists more power at the state [level], and then you don’t need lawyers … Maybe they [tenants] win sometimes, don’t get me wrong.”

But, he added, if landlords could spend less to evict tenants, they might be more inclined to take risks on tenants with eviction records.

In Connecticut, people can pay to subscribe to civil and family court case data that includes eviction filings. The filings are also available publicly through a search online.

The filings are typically available online for a year if the landlord withdraws the case or three years if there’s a judgment issued, said Elizabeth Rosenthal, deputy director at New Haven Legal Assistance Association.

This means that even if a tenant wins the case or a landlord decides not to evict, just the existence of the filing can cause problems for the tenant in the future. In some cases, a person with the same or similar first and last names who lived at the address of someone who was evicted — for example, a child with the same first and last names as their parent — have later struggled to get housing.

Tenant screening

It has been years since the April 2019 eviction with her name attached was filed, but Iliana Pujols still struggles to find landlords who will rent to her.

She’d been living with her mother in Waterbury and moved out. Her mother never had an official lease, Pujols said, and she moved out after her mom came back from a short stint in prison.

“I made the decision to get my own apartment, and then a couple of years later, when I tried to move, the agency I was working with to find an apartment was like, ‘You have an eviction on your record,’ and I was like, ‘That’s impossible, this was my first apartment,’” she said.

It turned out, her mother had been evicted, and the landlord had included both her and her mother’s names in the court filing. Even though Pujols was removed from the case, the record is still attached to her name in the online system.

She eventually found a landlord willing to rent to her, but it’s still difficult.

Data current as of October 2022. Chart: Ginny Monk / CT Miror Source: CT Right to Counsel

She moved into a new apartment earlier this year, for example, but later decided the rent was too high for her income. She gave her landlord notice that she is moving in March 2023 but hasn’t yet been able to find a new place to live.

Despite the amount of time that’s passed, a good job and no significant debt, Pujols is having trouble. She’s got the paperwork saying she was removed from the case, and Waterbury court officials said they’d vouch for her if a landlord calls. But she’ll have to find someone willing to make that extra call.

“It's super, super complicated to reverse something like an eviction on the record,” Pujols said. “It's not something that's easy, especially for younger people who don't know all that stuff. And it makes living comfortably very hard to do.”

Even once the state’s judicial department takes the eviction offline, tenant screening companies that have already purchased the data may have the record in their system.

There have been efforts to change the records, largely pushed by legal aid advocates, Shay said.

During the last legislative session, lawmakers considered a bill that would have required the judicial branch to remove information about eviction filings if they were withdrawn, dismissed or decided in the tenant’s favor, within 30 days.

The law also would have required evictions decided in favor of the landlord be removed after a year. Despite support from housing advocates and passage through the legislature’s Housing Committee, the bill didn’t get a vote in either chamber.

“The Judicial website itself warns users against using the data for tenant screening, but it is routinely used for this purpose anyway,” wrote Raphael Podolsky, an attorney with Connecticut Legal Services in public testimony in support of the bill.

Belongings of evicted people in New Haven are stored at a warehouse at New Haven Public Works Department, waiting to be picked up. Five to six evictions take place a week on average, said Tariq Dasent, an employee at the department. YEHYUN KIM / CTMIRROR.ORG

Belongings of evicted people in New Haven are stored at a warehouse at New Haven Public Works Department, waiting to be picked up. Five to six evictions take place a week on average, said Tariq Dasent, an employee at the department. YEHYUN KIM / CTMIRROR.ORG

Advocates listed eviction records as one of the most important reforms to pursue in the upcoming legislative session. The group Growing Together Connecticut plans to prioritize eviction prevention, among other housing-related measures, in the upcoming session, members said during a December news conference.

“When people are evicted, they're ripped away from communities where they have that support, they can no longer send their kids to schools where their teachers know them and know how they learn,” said Rev. Vanessa Rose, of the First Church Congregational in Fairfield. Rose spoke at Growing Together Connecticut's news conference.

“It really just uproots people's lives and makes it so hard for children to flourish and thrive because of this eviction cycle.”

"Notice to Quit," a multi-part examination of evictions in Connecticut and their effects on children and families, was produced as a project for the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2022 National Fellowship and its Kristy Hammam Fund for Health Journalism. This project also was supported by the Center’s Engaged Journalism Initiative.