How The Denver Post started a conversation while covering youth suicide in Colorado

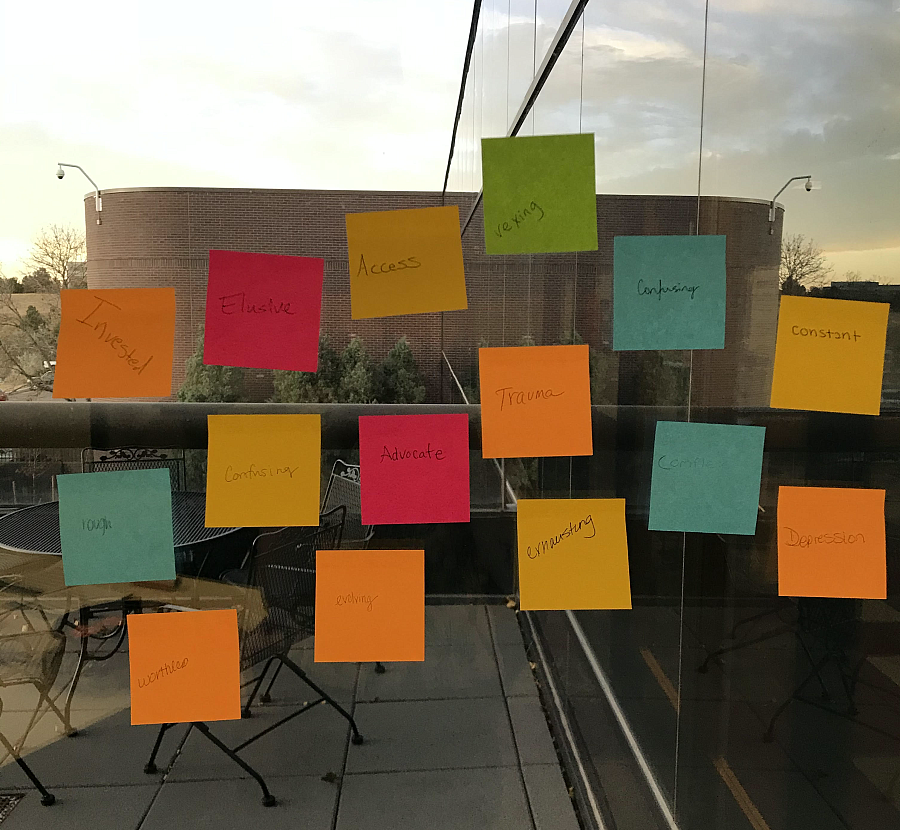

We asked meeting attendees to describe their experience with mental health in one word and put it on the Post-it note. Above, notes from the icebreaker in Colorado Springs.

(Photo by Danika Worthington/The Denver Post)

When I tell people that I’m reporting on youth suicide in Colorado, I often get a similar response: Are you familiar with the suicide reporting guidelines?

The response is reasonable, and after months of reporting on this topic, expected. But it also reflects how fear and stigma create barriers to having open and public conversations about this growing health issue.

In an effort to help break down these barriers and understand how youth suicide is affecting communities across the state, The Denver Post hosted community conversations in five counties over several weeks this fall. These events were held off the record because one of our main goals was to build trust from the people most affected by this issue. The other two goals were to develop story ideas and begin building an audience for our coverage.

The community conversations are part of The Post’s larger project investigating youth suicide in Colorado and whether enough is being done to address the issue. We decided to cover this topic because teen suicide is on the rise in our state and we’ve seen it affect many communities here after recent deaths and school threats. The project is receiving mentoring and financial support from the Fund for Journalism on Child Well-Being, a program of the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism.

One of the biggest takeaways from the events was that they gave us an opportunity to address, and hopefully alleviate, concerns individuals might have about stories on suicide. Those concerns vary, but one of the most common ones is the fear that exposure to suicide, including through news reports, can increase suicidal behaviors.

This phenomenon is called contagion. Researchers don’t know much about the science behind contagion, but guidelines were created by suicide prevention experts and journalism organizations to help reporters cover suicide without causing harm. However, they are not meant to silence conversations -- or stories -- about suicide, said Dr. April Foreman, a psychologist and board member of the American Association of Suicidology, a suicide prevention nonprofit.

“We put a lot of burden on the ins and outs of talking about suicide, especially with journalists,” Foreman said.

During our community conversations, we explained that with our project we are looking at youth suicide as the public health issue that it is. Our goal is to investigate the systems in place and whether they are doing enough to address the issue in our state.

We’ve received mixed responses from the community on the type of stories they want to hear from us. Some want stories that examine barriers to mental health care, while others want stories that focus more on “what’s working” and on survivors. As a newsroom, we are having conversations about how we balance this with our role as a watchdog.

We were able to address some concerns some people have about news coverage of suicide through our conversations. In other cases, it will take more work to build trust. We will work to do that by continuing to be transparent about how we cover suicide and showing through our stories that we are reporting these stories truthfully and responsibly.

My editor and I used the events to explain how we use the reporting guidelines. At The Post we use the guidelines as a starting point for conversations on how we cover suicide, including when we think it’s in the public interest for us to deviate from them.

For example, we don’t report on individual suicides unless there’s another reason to, such as a police investigation. And in most cases, we do not describe the method used in a suicide death. However, in some cases, it might be necessary, such as with the death of Jeffrey Epstein. The manner of Epstein’s death is noteworthy because it occurred in custody, indicating that there was a system failure in the jail (his two guards are now facing criminal charges).

The experience has taught me that reporters and their editors should have constant conversations on how to cover suicide in their newsrooms. While they should not blindly follow the guidelines, newsrooms should use them to report on suicide responsibly.

Here are other lessons we learned from the community conversations:

1) Have a mental health professional there. At our events we had a mental health professional available in case someone became upset by the conversation. I noticed this helped soothe some of the concerns nonprofits had about telling teens to come to our events.

2) Use an ice breaker and set ground rules. When we started the conversation, we set out some basic rules, such as explaining it was off the record and that we wanted attendees to respect each other. We did this to create an environment in which people felt comfortable opening up. We also started the conversation by having people describe their experience with mental health in one word on a Post-it Note (it was the only thing on record).

3) Meet people where they are -- especially teens. It was harder to reach teens and we had fewer show up than we expected. So we held a sixth conversation at a nonprofit that invited us to speak at their location. We also launched an essay contest on suicide and mental health and that gave us another way to reach teens. We did a lot of footwork to get the word out -- emailing teachers and handing flyers out to libraries -- and it has been successful.

4) Keep the conversations small, but advertise sooner. We thought people would be more likely to open up with a smaller crowd of 10 to 15 people so we didn’t initially advertise the events. Instead, we reached out to youth groups and suicide prevention organizations that might have been interested. This took more time than expected. We should have advertised sooner as we were rushing to get people to our first two events.

5) Set clear goals and expectations. Our team on the project knew we were holding these events with the three goals mentioned above, but we didn’t really set more detailed goals to measure the success of the events. While we sent out a follow-up survey after the conversations, it would have been better to keep track in real time the percentage of people who say they will follow the coverage or said the events changed how they view the project or The Post.