Bullying, Substance Use and Segregation

This story was produced as part of a larger project led by Deidre McPhillips, a participant in the USC Center for Health Journalism's 2018 Data Fellowship.

Other stories in this series include:

FOR 25 YEARS, MARCIA Zorilla worked as a health educator in San Francisco's Balboa High School, where she saw health problems and patterns of substance misuse change over the decades. Alcohol was the focus at one time, then ecstasy became the drug du jour. More recently, she says, students have taken to using marijuana and e-cigarettes.

But in 2017, a group of students Zorilla mentored in connection with the district's chapter of the School-Based Health Alliance recognized a different kind of health issue: Immigrant students in their school – especially those living in the country without legal permission – were often misunderstood and mistreated.

Her mentees were inspired to write a play about the problem, emphasizing the toll this type of alienation can take on a person's health.

"The students identified what was the most pressing health need and brought awareness to it by making it a communitywide effort to address it," Zorilla says.

While the play focused on mental health and unfairness in the system, there's evidence that discrimination like the kind noticed by Zorilla's students is tied to risky behaviors linked to both mental and physical health.

A U.S. News analysis of data from the California Healthy Kids Survey for the 2017-18 school year found that high school students in the state who said they'd been bullied at school because of their race, ethnicity or national origin within the past 12 months were twice as likely to have smoked cigarettes. Alcohol consumption was higher among this group as well, as were reported usage rates for marijuana, cocaine and heroin, and for prescription opioids, sedatives or tranquilizers.

And on the community level, a deeper dive points to a factor that can further fuel the hidden harms of bias-related bullying: segregation.

While overall rates of bias-related bullying are generally lower in California counties where residential segregation by race has been highest, a new U.S. News analysis shows bullying that does occur in these more segregated counties may be more harmful. On average, students who were both bullied for their race, ethnicity or national origin and more likely to have used alcohol, cigarettes or marijuana tended to live in more racially segregated counties than their bullied peers who were less likely to use such substances. Repeated substance use also was more common among these students in more segregated communities.

Despite its history as a hotbed of social activism, the Bay Area has grappled with segregation for decades. A recent report from the University of California–Berkeley's Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society found that the area was more segregated in 2010 than it was decades ago. And though San Francisco itself has seen improvement, it's still considered an area of high segregation.

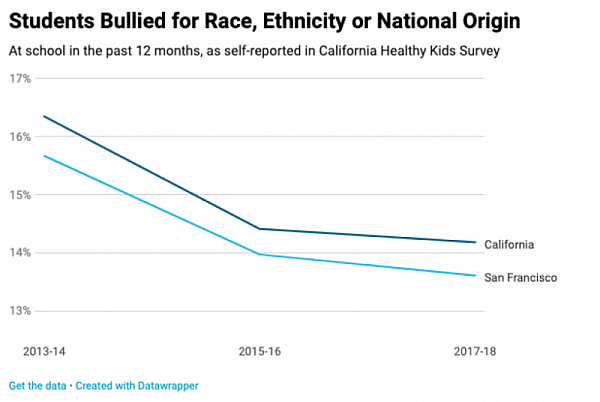

Meanwhile, though bias-related bullying has declined among high school students in San Francisco – dropping from 15.7% in Healthy Kids Survey data for the 2013-14 school year to 13.6% in data for the 2017-18 school year – the association between that bullying and risky health behaviors in the county is decidedly more severe than on average across the state.

Yannira and Matteo Castillo.Meredith Nierman / GBH News

In San Francisco County, students bullied over their race, ethnicity or national origin were about 20% more likely to have smoked a cigarette than other students across the state who had experienced similar discrimination. They were 13% more likely to have consumed alcohol and about 5% more likely to have used marijuana, the U.S. News analysis of 2017-18 survey data shows.

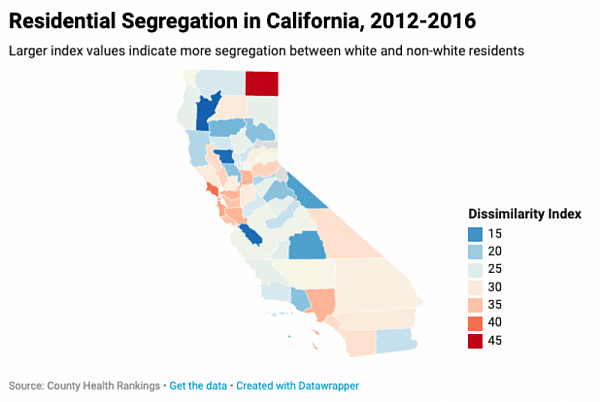

Risky health behaviors were also more common than average among students who were bullied in Sacramento and Los Angeles counties, both of which are as racially segregated as San Francisco, according to an index of white versus non-white segregation used by the University of Wisconsin's County Health Rankings project. (The index incorporates data from 2012-2016 and does not measure segregation of members of the Hispanic population, who can be either white or non-white.)

Research on the relationship between segregation and the disadvantages it creates in communities where most residents are not white – including in causing health disparities – is plentiful.

"Experiences such as discrimination and segregation get into the body to display patterns of burdensome health in groups that others that don't experience discrimination don't show," says Lisa Bowleg, a social psychologist who has researched the relationship between racial identity, sexual identity and drug use.

Yet the connection between segregation and health can also be nuanced and complex.

For example, research by social psychologist Frederick Gibbons and others found that while discrimination is a clear predictor of a victim's substance use, greater neighborhood segregation actually predicts less substance use.

"We found that black kids who had more exposure to white kids were more likely to experience discrimination and therefore more likely to use substances," Gibbons says. "A lot of teenage substance use is socially determined, not psychological, and white kids use more than other groups."

Since segregation creates a barrier between white students and non-white students, it essentially can serve as a buffer from both harassment and the negative influence that exposure to white students can bring in regard to substance use.

For example, the U.S. News analysis shows Modoc County and Marin County – the two most racially segregated counties in the state, according to the County Health Rankings index – were among the 15 counties with the lowest rates of bias-related bullying in 2017-2018 survey data. White students in those counties were 36% more likely to have consumed alcohol and 24% more likely to have used marijuana than their non-white peers.

However, Gibbons, a professor at the University of Connecticut, emphasizes that such findings are not a reason to promote segregation. Instead, he says, they should be used to actively encourage strong familial and cultural bonds that can help protect young people and lead to positive health outcomes.

"There are a number of negative things correlated with segregation – poverty and environmental stress, pollution, for example – and those are the kinds of things that promote unhealthy behavior more so than being in a black neighborhood," Gibbons says. "Those kids are learning about their culture and getting socialization from their parents, both predictors of healthy outcomes."

The student population of the San Francisco Unified School District was 10.5% white in 2017-18, though about a third of the district's high schools had a population that was less than 5% white, while more than 40% of one high school's student body was white. Asians accounted for 40% of students in the district overall, with Hispanics and African Americans making up 27% and 7%, respectively.

Gibbons speculates that the exacerbated relationship between bias-related bullying and substance use in San Francisco may have something to do with how attuned teens in the county are to recognizing discrimination when they see it. In other words, the buffer segregation provides may lose its effectiveness if discrimination is deeply rooted within a community.

Students in San Francisco likely have "more interaction with and awareness of the issue," he says, noting that "the impact of early and cumulative discrimination is undeniable."

In an email to U.S. News, a spokesperson for the San Francisco Unified School District says the district's Health Programs office is addressing racial equity in health through avenues that include "relevant and culturally sensitive (health) education" for students; on-site staff like social workers, nurses and teachers equipped to handle issues with "language and cultural specificity"; and targeted services offered through community-based organizations.

Such efforts often are key, yet Bowleg and others argue that fixing the issue will take system-level, communitywide change.

"This problem is part of a larger ecological system, a larger context where in San Francisco and elsewhere people who look like you have been pushed out and there are signals in society that tell you you don't matter," Bowleg says.

"There are so many signals from the environment that people take in about place and where they belong," she says. "Put racial bullying on top of it, and of course it will manifest in negative ways."

[This article was originally published by U.S. News.]