Death, Job Loss And Remote Learning: The Pandemic’s Toll On One Chicago Family

This project by Sarah Karp was reported with the support of the Fund for Journalism on Child Well-Being, a program of the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2020 National Fellowship.

Her other stories include:

Sarai Camarillo (right) shares headphones with her sister, Isamari Lucero, 13, as she learns remotely from their Little Village home during the pandemic.

Michelle Kanaar / WBEZ

It’s a busy Thursday morning in mid-November inside a small first floor apartment in Little Village on Chicago’s Southwest Side. A 13-year-old girl with pigtails and a 6-year-old boy with a round face and big brown eyes have their laptops open and are trying to listen to their teachers.

A 4-year-old boy is perched on the couch playing a handheld game.

Sarai Camarillo helps her 6-year-old son with math. Camarillo’s mother, Candelaria Lucero, is in the kitchen making 50 chili rellenos to sell in a factory. Camarillo’s husband is also home, trying to keep busy and stay quiet.

Two of these children are among the groups identified by Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot and Chicago Public Schools CEO Janice Jackson as struggling the most with remote learning. The 4-year-old, Isaac, is in preschool and Isamari, the 13-year-old, has a developmental disability. Of the three children in this apartment, those two are indeed having the most trouble. The 6-year-old first grader, Noah, is doing OK, but is increasingly frustrated as he flies through work and has a hard time getting the attention of his teacher.

But the family decided not to send the children back to school for in-person learning. The return began this month, though Chicago Teachers Union members are voting through Saturday on whether they want to collectively refuse to return on Monday over safety concerns.

The virus has already devastated Camarillo’s family, killing her father and destabilizing the entire family. They say they can’t take any more.

“It is really important to me that they don’t fall behind,” Camarillo said about her children. “But if it is not safe, I am not going to send them.”

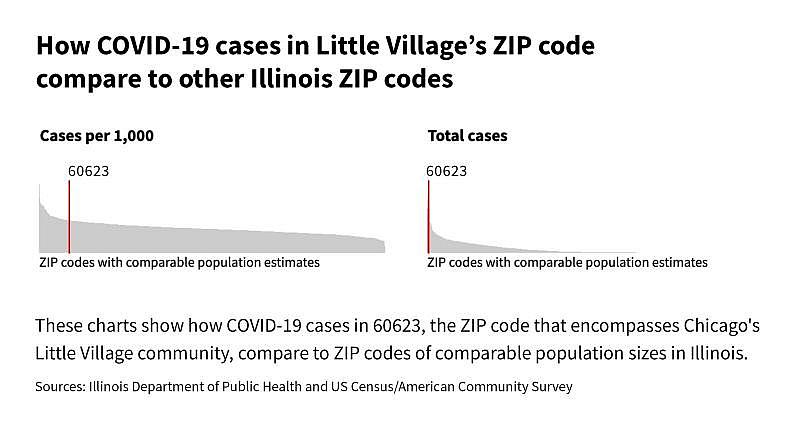

They feel like the virus is all around and too close. In the zip code that contains most of their neighborhood, Little Village, one in every nine people has had a confirmed case of COVID-19. Some 226 people have died, the most in any zip code in the city.

The pandemic has also sent a ripple effect through all aspects of the daily lives of families in Little Village. Camarillo’s family went from working hard at several steady jobs to suffering economic, housing and food insecurity.

Neighborhood-level statistics on how the pandemic has affected employment, housing and hunger are not yet available. But in a moment-in-time survey this fall by the U.S. Census, a quarter to a fifth of Black and Latino families in Illinois said they did not have enough food to eat or have confidence they could pay their rent.

“All of these things are all kind of colliding,” said Bill Byrnes, who analyzed the census data for a project of Voices for Illinois Children. “There were barriers before, and now they have been kicked into overdrive.”

Valerie Coffman, who works for Enlace, a social service agency in Little Village, said she has spent most of her time over the last year just helping families survive. She was hired to connect families with preschool programs.

Coffman said she has worked with families without electricity, who are facing eviction and need food. Coffman tells one wrenching story after the other — the mother without electricity charging her phone in the car so her daughter can use the hotspot to do school work, the little boy a mother left at a corner store because she had no one to watch him while she went to work.

“All of these things are all kind of colliding. There were barriers before, and now they have been kicked into overdrive.”

— BILL BYRNESE, VOICES FOR ILLINOIS CHILDREN

Coffman said many families are undocumented or are in mixed-status households and fear getting any government support. She explains that a Trump-era rule made it more difficult to get citizenship after receiving welfare or other public benefits. This rule was rejected by a federal court in December, yet it still sent a message to immigrants, she said.

And because of their immigration status, many parents in Little Village did not get the initial pandemic relief stipend from the federal government or unemployment benefits.

Camarillo is a U.S. citizen, but her husband and her mother are not. She has applied for help paying for her gas and electricity bills, but when she runs into obstacles, she doesn’t push. The family doesn’t want to bring attention to itself.

From left: Candelaria Lucero, daughter Isamari Lucero, grandsons Noah Ayala and Isaac Ayala, son-in-law Enrique Ayala, and daughter Sarai Camarillo. Michelle Kanaar / WBEZ

‘It’s not going to happen to my family’

But this family’s story begins and continues to be about grief.

Before everything shut down in March, Camarillo, her husband Enrique and their two sons lived by themselves in their small apartment on Cermak Road. It is in old greystone. During the summer, Caramillo puts plants on the stairs and, on the porch, there is a folding chair where an older gentleman, who lives upstairs, likes to sit.

It was just a few blocks from where her mother, father and her youngest sister lived.

The two families were tight: Camarillo’s husband and her father had the same two jobs, one at a restaurant in Schaumburg and the other at a factory. They traveled to and from work together.

Meanwhile, Camarillo, who is 27, worked mornings at a cupcake shop downtown. She went to school to be a baker. “It was like my dream job,” she said.

Her mother, Candelaria Lucero, sold candy, chips and homemade glazed donuts outside nearby Spry Elementary, where her grandson and daughter Isamari are students. Isamari smiles broadly as she remembers walking out of school and seeing her mother and getting free chips.

Because Lucero was often outside Spry and her two adult daughters also attended Spry, she has a deep connection to the school.

It’s from this place that Lucero also fell in love with the community. She talked to the mothers and the children, the teachers and the principal and the people walking by.

So when schools closed because of the pandemic, Lucero not only lost her place to sell goods, she also lost all the people who would fill her days with joy.

But like so many early on, the family she was not all that worried about the virus. “I thought it’s not gonna happen to my family,” Camarillo said.

Sarai Camarillo’s parents Candelaria and Margarito Lucero grew up in the same town in Mexico. ‘He was my first boyfriend,’ says Candelaria. ‘We went our separate ways and we both had children with other partners. Then we reunited here [in Chicago].’ (Courtesy of Candelaria Lucero)![Sarai Camarillo’s parents Candelaria and Margarito Lucero grew up in the same town in Mexico. ‘He was my first boyfriend,’ says Candelaria. ‘We went our separate ways and we both had children with other partners. Then we reunited here [in Chicago].’ (Courtesy of Candelaria Lucero) Sarai Camarillo’s parents Candelaria and Margarito Lucero grew up in the same town in Mexico. ‘He was my first boyfriend,’ says Candelaria. ‘We went our separate ways and we both had children with other partners. Then we reunited here [in Chicago].’ (Courtesy of Candelaria Lucero)](/sites/default/files/styles/inline_image/public/u106571/karp_4.jpg?itok=zvl8ln3M)

At first, they were more worried about keeping up with the bills. Camarillo stopped working to take care of her two young sons. Her father and husband had their hours cut at the restaurant and went looking for different work. Her father eventually picked up some temporary hours at a second factory.

It is there, in April, that the family suspects he contracted COVID-19. In fact, they think the reason the factory was looking for temps was to take the shifts of employees who’d already gotten sick.

Camarillo said her father went downhill fast, but was reluctant to go to the hospital. “He was scared,” Camarillo said. “People were saying you could die there.”

Finally, he got so sick that they took him to the emergency room. Because of COVID, no one could go in with him. So they went home and waited by the phone.

For five excruciating hours, the family heard nothing until finally, she called the hospital. They told her he had died. His name was Margarito Lucero.

To make things worse, when they went to get his belongings from the hospital, they couldn’t be found.

“He would always wear this necklace and my sister keeps asking for it,” Camarillo said. “But every time I call the hospital and ask for it, they say they don’t know where it is.”

When the Spry Elementary community got word of Margarito’s death, the teachers and staff immediately kicked into high gear. They created a GoFundMe page, which raised about $8,000 for the family. It allowed them to pay to have Margarito cremated and sent to Mexico where he could be with relatives. The teachers also put the family in touch with Spry Angels, a mutual aid group that provided them food and medicine.

Candelaria Lucero holds an old photo of her husband Margarito and daughter Isamari. Margarito died of COVID-19 in May. Manuel Martinez / WBEZ

Banding together as a family

Like her husband, Candelaria Lucero got the virus. Then, Camarillo got sick.

During this time, Camarillo’s two children stayed with Lucero’s other adult daughter. The family didn’t want the children getting sick too.

After schools closed down in March, it took a while for Chicago Public Schools to start regularly offering remote learning. Camarillo’s family wanted the children to participate, but like so many families, they did not have an internet connection.

So in the spring, they used the hotspots on cell phones. Camarillo said the connection was often terrible, but they muddled through.

Camarillo said she was especially desperate for her 6-year-old son to stay on top of work. When he was a toddler, she spent a lot of time with him going over his letters and teaching him how to read. “The teacher last year said he was a year ahead of the other kids,” she said. “I want him to keep up.”

Camarillo decided to stay home to help her two kids and also to support her mother and her younger sister, Isamari. Candelaria Lucero moved in with them after her husband died and her landlord came demanding the rent.

“I told him, I could not go to the bank because I was sick,” Lucero said. By then, in May, there was already an eviction moratorium in place, but that did not stop him from threatening her.

Lucero said she decided not to fight. For one, the apartment was in bad shape with holes in the ceiling. Also, she had just lost her high school sweetheart and didn’t want to be alone.

Sarai Camarillo supports her 4-year-old son, Isaac Ayala, for his daily hour of remote learning. Camarillo quit her job at a bakery so she could help her kids as they learn from home. Michelle Kanaar / WBEZ

Now, three adults and three children live in a two-bedroom, one bathroom apartment.

And the only adult working outside the home is Camarillo’s husband. But over the past 10 months, it has been inconsistent, with several restaurants and factories giving him only a couple of hours a few days a week.

“It is barely enough to catch on the rent,” Camarillo said.

She and her mother do what they can to make money. Lucero caters any events still taking place and cooks food to be sold outside factories. Camarillo uses coupons to buy things like household cleaning supplies and then sells them from her living room. The front room of the house resembles a mini-store, with products lining shelves.

Schooling amid trauma

When school resumed this fall, the children got off to a good start.

Camarillo bought her 6-year-old a little folding table for his school-issued laptop and posters to hang featuring the alphabet and the days of the week. It looked like a mini classroom.

She also had signed up for the free internet program offered by the city. On the second day of school, they got the box and, by the third day, they were able to connect.

The 6-year-old was serious when his teacher appeared on the screen. Like in all remote classes, the early days were a little chaotic. Some children were shy. Some didn’t know how to mute. But the teacher soldered on and found herself singing the day of the week song to the Addams family tune and encouraging the children to join in.

Camarillo decorated her 6-year-old son Noah’s work space to look like a mini classroom, with posters featuring the alphabet and days of the week. Michelle Kanaar / WBEZ

Isamari mostly did her work on a bed. In September, Lucero said her daughter seemed determined. She said wanted to work hard to honor the memory of her father, Margarito eight months after his death.

“He would tell her, ‘you are always going to focus on studying,’” Lucero said. “And now it is surprising because I have teachers calling to congratulate me. They say, ‘Isamari is learning very well.’”

It took two weeks for the 4-year-old to get enrolled in a preschool and, when he did, it wasn’t at their school, Spry, but at another local school called Saucedo, which was OK with Camarillo.

But she worries about her son. Some days he sits and pays attention. But a lot of days, he just refuses. She says because school is new to him, remote class seems like a boring television show his mother is forcing him to watch.

The Spry community has remained a constant source of support. The counselor helped Isamari and the 6-year-old make a memory box for Margarito. The teachers call the family to check on them.

Yet, Camarillo said she can see that the children are suffering. Her 6-year-old surprises her by breaking down when he remembers his grandfather, Margarito. Also, as much as he tries at remote schooling and getting good grades, he is distracted.

Isamari is also having a hard time lately. She tries to be brave, but her mother often hears her crying at night. By the end of the first quarter, her grades dropped. She said it is difficult to do work without the teacher right there to help her.

Sarai Camarillo says the pandemic has been especially hard on her sister, Isamari Lucero, 13, who has been dealing with the challenges of remote learning and the death of her father, Margarito Lucero. Michelle Kanaar / WBEZ

Her sister and her mother are really worried about her.

“She has talked to the doctor about going away, about suicide,” Camarillo said.

A lot of research shows the impact of trauma on children. They can have trouble sleeping, be clingy, have heightened emotions and be easily distractible. Studies have already shown that children’s mental health has suffered during the uncertainty of the pandemic.

Add to that death, homelessness and economic instability, and experts predict that children who have experienced all of these will need extra support.

Isamari’s family is trying to find a place to get her help, but they have no money for any counseling. It’s another sign of the profound ripple effects of the pandemic on this family, another way their lives have been forever changed.

So instead, they are keeping a close watch over Isamari and praying.

Sarah Karp covers education for WBEZ. Follow her on Twitter @WBEZeducation and @sskedreporter. This story was reported with the support of the Fund for Journalism on Child Well-Being, a program of the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2020 National Fellowship.

[This story was originally published by WBEZ Chicago.]