Ending the Pandemic Means Getting Vaccinated. But Many Oregonians Will Be Hard to Convince.

This story was produced as part of a larger project led by Rachel Monahan, a participant in the 2020 National Fellowship.

Read her other stories here:

Mimi Luther Dreads the Prospect of Flu Season Mixed With a Pandemic. She Begs You to Get a Flu Shot.

Prominent Anti-Vaccine Pediatrician Dr. Paul Thomas Has License Suspended by the Oregon Medical Board

These Two Doctors Provide the Last Signatures Before Oregonians Get a COVID-19 Vaccine

(Wesley Lapointe)

As Oregonians wait to get a COVID-19 vaccination, many overlook that we are all waiting on our fellow Oregonians to get vaccinated as well.

Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, recently estimated that as many as 85% of Americans need to get the vaccine to bring the pandemic under control. Without that kind of vaccination rate, the virus can still spread rapidly, and even people who've been vaccinated aren't fully guaranteed they're safe.

The challenge: In Oregon, the percentage of people who say they won't get the vaccine is too large.

Some 25% of Oregon women and 21% of men say they won't get the shot, researchers at the University of Oregon found in a December survey. Another one-third of Oregonians say they aren't sure. Their fears include that the vaccine might have side effects, or it could even give them COVID-19.

Such numbers are largely consistent with the rest of the nation.

Among the Oregonians hesitating is Zia McCabe.

The longtime bassist for the Dandy Warhols, McCabe actively fought the campaign in 2012 to fluoridate Portland's water. And she's not eager for a COVID-19 shot.

"I'll wait as long as possible," she says, "to see what happens to the people at the front of the line. I'm in no hurry, would be the best way to put it."

That might seem surprising. But it shouldn't. Oregon is fertile ground for vaccine skeptics.

In the 2018-19 school year, for example, parents of 7.7% of Oregon's kindergartners claimed an exemption from at least one vaccine for their children. Tied with Idaho, Oregon had the highest exemption rate in the nation, according to an analysis by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

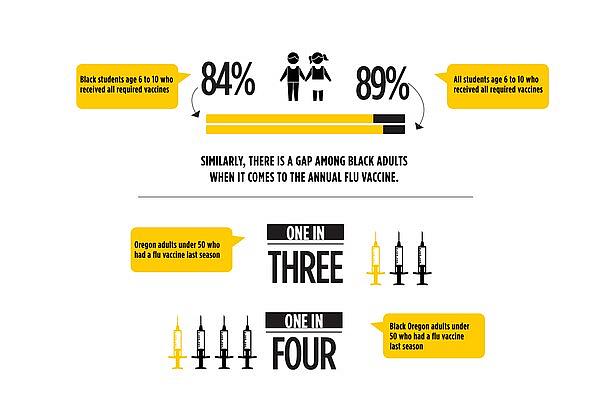

And less than 39% of Oregon adults under 50 got the flu shot last season.

"We've not done a great job in the U.S. at large at getting people to take vaccines," says Dr. David Bangsberg, founding dean of the joint Oregon Health & Science University-Portland State University School of Public Health. "Some communities here in Oregon, the vaccination rate is down to the 30-to-40-percent range. After vaccination levels dropped to that level, we saw several measles outbreaks. The historical precedent suggests [acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccine] will be a challenge."

Not everybody who opposes vaccination does so for the same reasons.

WW has talked to more than a dozen local experts—including academics, epidemiologists, public health officials, and nurses who care for specific Oregon communities—about who is and isn't enthusiastic about rolling up their sleeves.

They identified key groups whose opposition to vaccination is significant and could stall the state's and the country's emergence from COVID-19.

These groups, and others, will need to drop their opposition to vaccination for the shots to work statewide. Persuading them is the task Oregon must accomplish if grandparents and the medically infirm are to stop dying in shockingly large numbers, if you and your neighbors are to burn your masks in a backyard bonfire, hug your aging mothers, or engage with abandon in whatever socially undistant freedom you so desperately crave.

A coalition of leftists and conservatives banded together to defeat the fluoridation of Portland’s water at the ballot in 2013. (Kurt Anderson)

Crunchy Portland Earth Mothers

It isn't just Republicans from rural Oregon who worry about vaccines. It's Portlanders' natural oils-loving neighbors who send their kids to Waldorf schools.

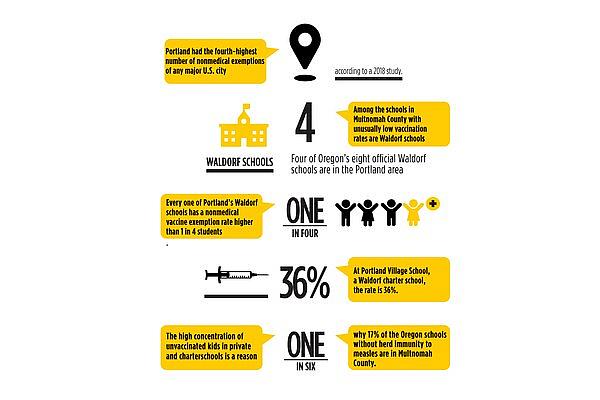

In 2018, researchers identified 15 "hot spots" across the U.S. where a significant portion of schoolkids in a major metro area didn't receive childhood vaccinations. Portland had the fourth-highest rate of nonmedical exemptions of any major U.S. city.

"There's definitely vaccine skeptics in my area of the world, for sure," says state Rep. Rob Nosse (D-Portland), who represents one of the most left-leaning districts in the state. "They tend to be people that favor more naturopathic medicine."

Many of them, says Nosse, are moms.

"They are smart women," he says. "They're not dummies. For them, it's about a different approach to science and medicine; it's not about church and Jesus."

Nosse had a close encounter with these moms in 2019, when he backed a bill that would have no longer allowed them to claim a philosophical reason not to have their school-aged children vaccinated. Among Nosse's opponents: naturopaths and Waldorf parents. (The bill failed.)

Portland is a hub of naturopathic medicine, with three area colleges that train doctors in the alternative medicine. (A dozen naturopaths testified against Nosse's bill.)

WW contacted six Portland naturopaths. Four didn't respond. One said he'll follow CDC guidance and the other said she'd take a case-by-case approach with patients.

Among the schools in Multnomah County with unusually low vaccination rates are Waldorf schools, which promise a free-range education for children of progressive parents.

Four of Oregon's eight official Waldorf schools are in the Portland area, and every one has a nonmedical vaccine exemption rate higher than 1 in 4 students. At Portland Waldorf School, a private school in Milwaukie, every other student has an exemption from at least one vaccine.

The high concentration of unvaccinated kids in private and charter schools is a reason why 17 percent of the Oregon schools without herd immunity to measles are in Multnomah County.

"The schools are points of accumulation. If you're going to put your kid in a Waldorf school, you might be driving from all over the region," says Steve Robison, the Oregon Health Authority's immunization epidemiologist. "They draw like-minded people. Either they don't like immunization or they don't like being told what to do."

But does this mean crunchy progressives won't get the COVID-19 vaccine? Ask Sandra Ganey, 55, a yoga teacher and water fluoridation opponent who lives in the South Tabor neighborhood.

In the past month, she's posted a string of warnings about the vaccine on her Facebook page, including a Jan. 3 post about how coronavirus vaccines have caused "animals to die at a high rate" in past studies.

But she won't talk to WW. "Nobody trusts you to do fair reporting," she said. "Maybe you could learn more about these important issues with some reading."

McCabe, the Dandy Walhols bassist, says she is seeing some crossover from the coalition that fought water fluoridation. In 2013, an alliance of environmentalists, libertarians and others successfully overturned a plan by the city of Portland, backed by public health officials and equity groups, to add fluoride to the water supply. Portland voters rejected fluoridation by a 20-point margin.

"A doctor can't force you to take something even if it's going to save your life," McCabe says. "I try to take each [decision] case by case, be really patient, and make my own decision. I am certainly not on any Western medicine bandwagons."

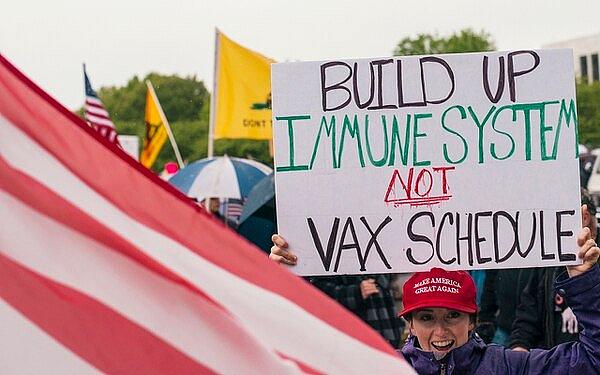

STICKING POINT: As early as last May, conservative protesters of COVID-19shutdown orders expressed their distrust of vaccines at the state Capitol. (Aaron Wessling)

Anti-Mask Republicans

The highest-profile opponents of vaccination are a large subset of supporters of President Donald Trump, many of whom doubt COVID-19 is a deadly disease.

Just half of Republicans say they will take the COVID-19 vaccine, according to Gallup's most recent national poll, a number that has not changed in the past three months.

On Sunday, Sept. 27, five weeks before Trump lost reelection, a crowd of 150 Oregonians gathered at the steps of the state Capitol to hear speakers warn of the dangers of vaccines. All but a handful opted against face coverings of any kind—at least one speaker referred to masks as "muzzles." A vendor in the crowd sold T-shirts with Gov. Kate Brown's face altered to include a Hitler mustache.

The advocacy group Oregonians for Medical Freedom sponsored the event with the American Patriot Society, a far-right group that has roughly 25 members but was actively recruiting outside the Capitol.

Brian Price, a mild-mannered father, manned the Oregonians for Medical Freedom table. He hasn't had his 9-year-old daughter vaccinated for any diseases, for philosophical reasons: "We believe the body has an immune response," he says, objecting in part to the number of vaccines children receive. "That is outrageous, that many vaccinations."

Price said he's a Republican, a conservative and a Christian but that the movement isn't about one party: "We will attend a Democrat rally."

Perhaps no Republican in Oregon plays a more pivotal role standing in the way of vaccine acceptance than state Sen. Tim Knopp (R-Bend). He's led much of the recent opposition to legislative attempts to increase vaccination rates.

"We are going to learn to live with the virus just like we live with other viruses," he tells WW.

STICKING POINT: As early as last May, conservative protesters of COVID-19 shutdown orders expressed their distrust of vaccines at the state Capitol. (Aaron Wessling)

Knopp, a moderate who is pro-mask, says he's still unsure whether he'll get the COVID-19 vaccine and he wants more information, "specifically regarding ingredients and reactions/injuries and deaths," he said. "I've seen the summary data. If they are looking to build trust with the public, they need to release more data."

He doesn't buy the argument that Oregonians will look to him to decide whether to vaccinate.

"Oregonians will choose to receive the vaccine based on their own research and trust in the actual product," Knopp says. "I don't believe Oregonians are going to buy political photo-op policy on the COVID-19 vaccine."

Immigrant Communities

A group of Eritrean immigrants recently discussed with WW a social media rumor swirling in their community: It says the vaccine is a means to inject them with the biblical mark of the beast, a medical twist on the Book of Revelation.

"There's a theory that connects the vaccine with the number 666, and people are saying…that the government has put something else in the vaccine," says a woman who identifies as Ms. Weldekidan, 68, who was a social worker in Eritrea who made sure people got the polio vaccine. She moved to Portland four years ago, and works at Goodwill.

"I don't know the contents of the vaccines," adds Mrs. Tadesse, 40, a mother of four who told WW she is also reluctant to get the vaccine. "I have read in the Bible, it states at the end of the world how people get 666 or the number of the beast. I have heard it on social media."

Such rumors fit a pattern that health experts see in several immigrant communities: viral online conspiracy theories about the sinister intentions of their new home's government.

Two years ago, the Russian-speaking population was at the center of a local measles outbreak that sickened 71 people in Clark County, Wash., and another four in Multnomah County.

Sara McCall, a lead nurse epidemiologist for Multnomah County, has been studying vaccine hesitancy among Russian speakers in Oregon. At least 50,000 immigrants from the former Soviet Union reside in the Portland area, where Russian is the third-most-spoken language.

"The themes we heard were a general mistrust of government and, in particular, how health care and government were entwined," McCall says.

In other words: Soviet immigrants left a nation where vaccinations were mandatory. Strong-arming them isn't likely to work.

"You think about the culture they came from, where they were oppressed and government had a lot to do with that," says Kuzmenkova. "It translates into a worldview."

Even two Multnomah County nurses from the Russian-speaking community told WW they were initially unsure if they'd get a COVID-19 shot.

"Coming from a country that was communist, there was very specific persecution, and you didn't really have a choice to get vaccinated," says Irina Grigorov, a clinical nursing supervisor with the county's Communicable Disease Services. "You were in school, a nurse came in and vaccinated all the kids without the parent's permission.

"Not providing the information, how is that different from saying, 'Get in line, we're going to give you something'?" she asks. "We don't know what's in it. We don't know what the side effects are."

An outdoor clinic at Portland Community College’s Cascade campus offers COVID-19 tests andflu shots in one parking lot. The flu vaccination drive is seeking Black Oregonians and immigrants. (Courtesy of Multnomah County)

Latinxs, who make up the largest minority group in Oregon, are also less likely to get annual vaccinations. Less than half of adults in Oregon got the flu vaccine. But fewer than 1 in 3 Latinx adults in Oregon got it.

And Latinx Oregonians are disproportionately impacted by COVID-19, with the virus four times more prevalent among Latinxs than non-Latinxs.

State officials last year identified seasonal farm workers, many of them Hispanic, as a group that will be difficult to reach with a COVID-19 vaccine.

The reason? The logistics will be complicated for getting the two doses required to people who travel from state to state picking fruit.

But there's also another problem. Many undocumented workers distrust the feds.

"I think that mistrust stems from years and years of policies that have hurt families," says Eva Galvez, a doctor with the Virginia Garcia community clinic. "Particularly in the last few years, we have seen anti-immigrant rhetoric and policies that are coming from our federal government."

Galvez herself feels a pang of anxiety about a shot that was rapidly approved.

"I'm getting this vaccine and I'm excited," she says. "But this is the first vaccine that I can honestly say that I will be getting with maybe just a little bit more trepidation. All of the medications that I prescribe have been vetted for years. This is new for even physicians."

In fact, distrust of the new COVID-19 vaccine is now so intense, some doctors say their patients no longer want their annual flu vaccines.

"I've heard people say, 'I've heard they can inject a bad virus,'" says Galvez. "That's been really challenging this year."

Charlene McGee says she understands Black Oregonians’ doubts about vaccines, and wants to allay fears as she inoculates people.(Courtesy of Multnomah County)

Black Oregonians

Rachelle Dixon, 53, is a Black community organizer and vice chair of the Multnomah County Democrats. She will not get a COVID-19 vaccine for as long as possible—ideally, two years.

She's concerned about side effects from a vaccine granted speedy federal approval. But she's also concerned that the U.S. often treats Black people as disposable.

"It hasn't been a pretty couple hundred years," she says. "All along this timeline, the medical community has shortchanged Indigenous and African American people time and time again."

State numbers show that Black Oregonians are among the groups with the lowest vaccination rates (see chart at right). What does Dixon think about the Black community not taking a potentially lifesaving vaccine after the pandemic has hit them the hardest?

When asked, she responded: "I think you are asking the wrong question," she says. "To say we don't have legitimate reasons, it's irresponsible—it pushes the community away. It's condescending and disenfranchising. There is a lot of pressure on Black people to abandon what's right for their own body so they can protect white bodies. That's highly problematic to me."

Vaccines in Black and White

Previously unreleased data obtained by WW from Oregon Health Authority show a gap in vaccination rates between Black Oregonian elementary school students and white students. "These small differences can still be meaningful for herd immunity," says Steve Robison, the state immunologist. "Black kids have lower immunization rates across most areas than do others."

Danaya Hall, a nurse who founded the Alliance of Black Nurses Association of Oregon earlier this year, says she will get vaccinated, but she understands Black Oregonians' hesitancy.

"Black bodies have historically never belonged to black bodies," she says. "When you have a person telling you to get a vaccine and at the same time they're not very nice to you or treating you like you don't know how to take care of yourself because you have diabetes and hypertension, this person is going to lose credibility. That's a lot of healing that needs to happen."

Such healing is the work of Charlene McGee, Multnomah County's program manager for a flu vaccination drive focused on Black people and African immigrants.

This isn't her first epidemic. In early 1990s, when McGee was in sixth grade, she and her family fled a civil war in Liberia and came to Portland.

McGee later returned to serve in the administration of Liberia's president, Ellen Johnson Sirleaf. But when Ebola hit, her aunt bought her and her young son airline tickets out. "She was like, 'You are getting out of there,'" McGee recalls.

She returned home to Portland and is here to fight this health disaster, persuading one Black Oregonian at a time to vaccinate.

That challenge was in evidence on a recent Wednesday afternoon, as a line of cars and pickup trucks snaked out of a COVID-19 testing site in a parking lot at Portland Community College just off North Killingsworth Street.

At the tent where they checked in, patients who'd scheduled a coronavirus test got an offer: a chance to receive a free flu vaccination, too.

But the offer of a free shot didn't generate a lot of interest. Only one car pulled into the flu shot line, while more than a half-dozen waited for a COVID-19 test.

The unenthusiastic response felt like a signal: A lot of Oregonians don't trust vaccines. And they won't be eager to try one to eradicate COVID-19.

"We took this work on very much aware of the mistrust between our community and government, and our community and vaccines," says McGee. "We also recognize vaccines as one of the greatest achievements in public health."

Rachel Monahan reported this story with the support of the Dennis A. Hunt Fund for Health Journalism, a program of the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism's 2020 National Fellowship.

[This story was originally published by Willamette Week.]