Endurance Test: Underserved Desi Grocery Workers Go to the Front Lines

This article was produced as a project for the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2021 California Fellowship.

Other stories include:

Chasing memories inside Silicon Valley’s Desi grocery stores

Dimple Jaani at the register at Trinethra on Pearl Ave

(Image Credit: Srishti Prabha)

Masala Heroes is a three-part series on Santa Clara County’s South Asian (Desi) grocery stores and their contribution to their community’s health. Check out part 1 and part 2.

When the pandemic hit in March 2020, some people stormed stores for toilet paper; my mom came home from Trinethra with a 10-pound bag of brown rice, different dals, and the largest bag of aloo (potatoes) I’d ever seen. In her version of an apocalypse, we would be eating rice, dal, and aloo with our hands for weeks. Little did we know, the real-life version of the apocalypse would last more than two years and affect our community in ways we had not imagined.

“Sometimes I would sit down in the car and cry.” – Dimple Ben

Dimple Jaani reflects on the past two years as manager of a Desi grocery store in Santa Clara County. As COVID-19 spread, fear and exhaustion gripped the essential workers of the pandemic.

Image Credit: Graphic created by Srishti Prabha in collaboration with India Currents and USC Center for Health Journalism.

“At the beginning of the pandemic, people panicked. I panicked too. But I take care of the store,” says Dimple Jaani, endearingly known in the South Bay Desi community as Dimple Ben (sister). “If something were to happen to me, what would I do? I handle employees and they are in fear too,” Jaani says, recalling days she worked from 9 am to 2 am, only to wake up and repeat the cycle.

Dimple Ben came from Gujarat, India to San Jose, California in 2004 in hopes of a better life and education – chasing the American Dream. Having started at the register at Kumud groceries (now known as Trinethra on Pearl Ave), sixteen years later this unassuming woman with a calm demeanor is the manager and the public face of the store.

“I feel like this is my own store. I care,” she says standing outside the front door. “98% of people think it is my store. People think, ‘This woman is always here.’” Dimple Ben’s thoughts are interrupted by a customer who has been looking for her and asks why she is not inside.

Dimple Ben’s experience reflects the challenges that the pandemic exacerbated for the Masala Heroes of Santa Clara County (SCC) – challenges that continue to affect them today: protecting against the spread of the virus in their stores; paying employees in the face of declining income, rising costs, and workers’ changing visa status; struggling to stock shelves; and responding to demanding customers. It has taken an emotional and financial toll.

Cleanup on Aisle 1

“Our family has been going to the India Food and Spices in Duarte, CA for groceries for almost 20 years. During the pandemic they followed all COVID-19 guidelines and continued serving the community.” – Mohna (omitted last name)

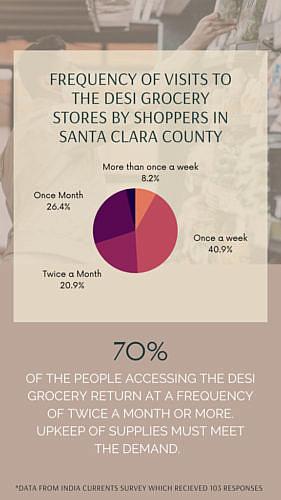

Throngs of South Asians have swarmed to their local Desi grocery stores to stock their pantries with healthy food. Many have found these stores a source of comfort during COVID, as they worry and cope with the loss of their family and friends thousands of miles away. Shoppers run in, grab groceries, and rush home to feed their children. Has the community at large considered what it takes to get their favorite Desi ingredients and the burden their Masala Heroes bear?

Surya Dixit, owner of Trinethra Supermarkets, in front of his store in Santa Clara. (Image Credit: Srishti Prabha)

For Surendra (Surya) Dixit, owner of the Trinethra Indian Supermarkets, the safety of the employees and customers comes first. But there’s a cost.

Masks for employees, sanitizer at the registers, plastic shields around the counters, extra cleaning, limits on the number of customers allowed inside – these add to expenses and cut income. In some months during the pandemic, the employees have run through about 400 masks and 800 gloves.

Dimple Ben ensures that her employees are vaccinated. She even made vaccination appointments for most of them.

Dixit estimates that the store’s daily average of customers – between 300-350 on the weekdays and up to 500 on the weekends – dwindled to about 200 a day as the pandemic kicked in. He tried to keep customers by offering curbside pickup and delivery.

Meanwhile, supply slowdowns hampered what he could sell. For example: An order of Maggi from India was delayed by three months and took six months to travel – arriving at the expiration period of nine months, making it unsellable.

“What should I do now? No one takes the product back,” Dixit says.

While the federal Paycheck Protection Program helped him pay employees who were working fewer hours than usual, it didn’t compensate for the added costs or the loss of revenue.

“I didn’t pay my employees a penny less,” Dixti passionately asserts.

On top of financial stress, Trinethra has battled criticism in-person and on the Internet. Some shoppers complained about expired items on the shelves; a few claimed they caught COVID at the store. Dimple Ben was frustrated. She felt customers should raise problems with her directly. “[Customers] don’t understand,” she says. “They just want to get their groceries and go. I have had to go by the rules. Lots of customers have been upset at times and it is horrible for me.”

Desi grocery stores, the owners, and their employees are on the receiving end of the criticism and it wears them down.

Culture and Care

“I worry…This looks like an easy job…[but] it’s a big responsibility. You have to think about the store and the people.” – Dimple Ben

Dimple Ben at her desk at Trinethra on Pearl Avenue (Image Credit: Srishti Prabha)

Dimple Ben is expressing signs of distress, yet her mental health is not on her radar.

Studies show that food retail and service employees have exhibited heightened levels of mental distress during the pandemic. But cultural norms and stigma about mental health impede people’s willingness to take action.

The South Asian Public Health Association (SAPHA) aggregates research on South Asian American mental health and finds that South Asians commonly express psychological stress with physical symptoms. Furthermore, the resistance among South Asian Americans to discuss mental health struggles imposes a barrier to receiving help.

“From my observation during the pandemic, the mental health issue is very dominant in these communities…and there is a stigma around getting labeled pagal (crazy),” says Sewa International Bay Area’s Family Services Coordinator Minal Joshi.

Joshi’s clients have shared narratives involving precursors to mental distress that force them into volatile scenarios. As Dimple Ben’s tale as a food retail worker unfolds, glimpses of her other hurdles come to light: housing insecurity (the elder woman renting to her feared contracting COVID due to the nature of Dimple Ben’s work, so Dimple Ben had to move), lack of healthcare, and a rigorous work life that doesn’t permit for a healthy diet. Joshi finds that many of those reaching out to contact Sewa International’s hotline searching for rental assistance, housing, and work placement are not aware of their mental health needs. Joshi probes to get to the crux of their health issues, building trust and combating cultural stigma to get to the truth.

Establishing mental health awareness is step one in helping workers get through their COVID-related struggles. The next step involves dealing with culture, immigration status, and providing safe outlets. The working-class and undocumented South Asians live in the shadows of Santa Clara County, hoping to remain undiscovered and reluctant to ask for help. As a response to COVID, South Asian Americans Leading Together (SAALT) finds that governmental efforts fall flat. States rely on South Asian American community organizations to fill in the gaps in access to health, food, housing, and employment, which ultimately leads to unequal consequences in this specific community. Many such organizations within California (Maitri, Jakara, SAHARA, Sewa International) tried to increase capacity and shift their goals to adapt to the changing needs of their clients.

“During the pandemic – losing jobs, being out of [visa] status, and being in a precarious economic situation – we saw mental health issues drastically go up,” emphasizes Rakhi Israni, National Spokesperson for Sewa International.

Behind the Register

“Generally, if we get sick, we have to tell the owner. We don’t have any insurance. We have to pay out of pocket.” – Dimple Ben

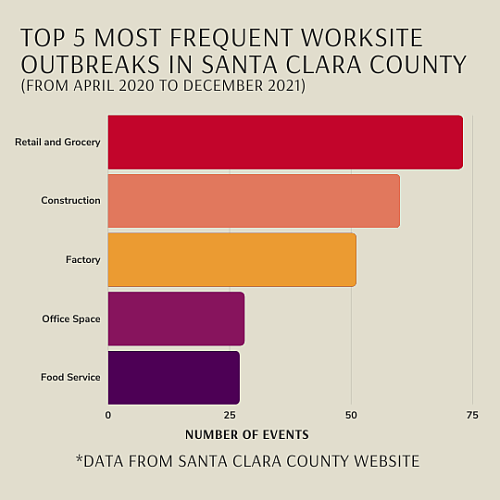

Image Credit: Graphic created by Srishti Prabha in collaboration with India Currents and USC Center for Health Journalism.

From 2020 to 2021, workplace COVID outbreaks in Santa Clara County have been highest at retail and grocery stores. However, none of the outbreaks appear to have been reported at any of the county’s 24 Desi grocery stores. Santa Clara County’s health department confirms that: “The County does not have a recorded outbreak associated with the [desi grocery] stores.”

Despite the high volume of ethnic grocery stores in SCC, very few report COVID outbreaks.

Why? Were there no cases because of a cultural inclination to abide by county guidelines or an inherent belief in science, or was there underreporting?

At ethnic grocery stores, the onus falls on the owner to report cases or help their employees report. If the immigration status of the employees is in question, it can deter the employees from reporting to their owner, or the owner reporting to the county.

Regardless of their immigration status, South Asians who come to California often pick up service jobs – generally ones where they can speak their native language and find an empathetic ear. When Dimple Ben came to the U.S. looking for a job, she said Kumud groceries was a good fit: “I’m not that well-educated…I didn’t speak good English, so it was nice that I could speak the language [I knew] at the grocery store.” Dimple Ben employs others that remind her of her start in the U.S.

When considering vaccinations, reporting, and possible exposure, the demographic of those acquiring jobs as essential workers at ethnic grocery stores and the type of data collected by county programs must be taken into account.

At Sewa International, Minal Joshi keeps track of those requiring rental assistance, job assistance, and food access. Joshi underscores the increase in South Asians with student visas seeking cash-paying jobs – cashier or bagger at the Desi grocery stores – after losing their on-campus jobs due to COVID. The type of person taking on a job at the grocery can vary, linked by the complicated history of immigration to the U.S.

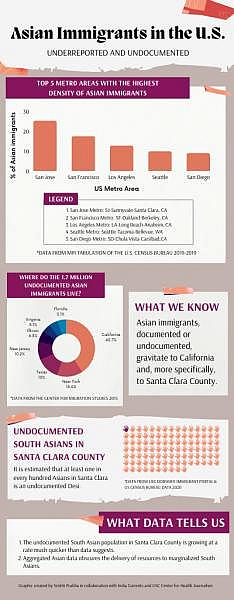

Since Dimple Ben arrived from India, Desi grocery stores have proliferated in Santa Clara County in response to demand. SCC is home to more Asian immigrants than any area of the country. Those who are undocumented remain underserved and unreported. Here is what we do know:

- Among the 1.7 million undocumented Asian Americans in the United States, 463,000 live in California, according to the Center for Migration Studies.

- In 2017, undocumented Asian immigrants made up 14% of the total undocumented population in the US.

- SAALT conducted a survey in 2019 that found that there are at least 630,000 Indians who are undocumented, which they report to be a 72% increase from 2010. South Asians are one of the fastest growing undocumented populations in the country.

At USC Dornsife Equity Research Institute, Data Analyst Arpita Sharma and Data Manager Justin Scoggins have spent the last few years, under Dr. Manuel Pastor’s guidance, estimating the number of undocumented South Asians in Santa Clara County by using the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey microdata from 2018. After working with this data, they conclude that there is very limited information available on undocumented Desi immigrants, their occupation, industry, and worksite locations. Sharma asserts, “The population size is small and difficult to capture due to its sensitive nature.” Their immigrant data portal estimates 4% of undocumented South Asians in the U.S., primarily Indian, reside in SCC – a conservative estimate that leaves a lot to be desired.

In an effort to reach Asian immigrants, Santa Clara County and Blue Shield partnered with local organizations like Asian Americans for Community Involvement (AACI) and Bay Area Community Health to distribute COVID-19 vaccines and provide care for those who contracted COVID. Little to no personal information was recorded, to ensure equitable service.

Sarita Kohli, President and CEO of AACI, says lack of data impedes efforts to help South Asians in SCC. She notes, “We do not ask for documentation. But actually, getting that information is important because then we are able to identify and deliver resources.”

SAALT’s report validates the undercounted and incomplete COVID data on Desi communities, often as a result of the use ‘Asian’, ‘Other Asian’, or ‘Unknown’ race categories on surveys. Disaggregated data is critical in ensuring all communities receive timely and culturally appropriate care and resources. AACI pushed for this key piece of information from Santa Clara County, and separation of the Asian demographic revealed that Vietnamese, Filipino, and Asian Indians were the most affected by COVID. This information would have remained entangled in the Asian demographics if it had not been for AACI’s efforts.

Kohli attributes the lasting COVID impact on the Asian Indian community to the high incidence of diabetes and hypertension in the population. COVID risks for undocumented South Asians prove to be a significant missing piece to understanding the impact of the disease in SCC. Santa Clara County says in a prepared statement that the data requested about COVID cases is simply not available in the state’s database. The information they get from the state includes the Asian demographic but is not specific to South Asians or Indians.

The paucity of information about these communities continues to complicate efforts to help frontline workers in places like the Desi grocery stores. As those employees are pushed to their limit mentally and physically, they ultimately end up as invisible members of their community, sidelined in the face of model minority myths.

SCC’s Desi grocery stores have gone through hard times and continue laboring in their mission to their communities. “People think a grocery store job is easy. No,” Dimple Bens as she stands on the sidewalk. “We work hard. People get tired.” She sees the line at the register growing and she rushes back inside to help her employees.

I waited 20 years to hear Dimple Ben’s story for the first time and she didn’t make it easy. She didn’t feel her story was significant and she couldn’t understand why I was so insistent on hearing it. But she is significant – for what she provides to the community and for how she gives voice to the many muted Desi narratives like hers.

Go back and read part 1 and part 2 of this series. This article was produced as a project for the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2021 California Fellowship.

Srishti Prabha is the Managing Editor at India Currents and has worked in low-income/affordable housing as an advocate for children, women, and people of color. She is passionate about diversifying spaces, preserving culture, and removing barriers to equity.

This article couldn’t have been written without the help of my editor, Patrick Boyle.

[This article was originally published by India Currents.]