Three Cultures, Two Shopping Carts, One Desi Grocery Store

This article was produced as a project for the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2021 California Fellowship.

Other stories include:

Chasing memories inside Silicon Valley’s Desi grocery stores

Endurance Test: Underserved Desi Grocery Workers Go to the Front Lines

Left to right: San Jose resident Rita Kumar with her groceries at Trinethra on Pearl Avenue; and Vinu Thyagrajan with her groceries at Trinethra on Pearl Avenue.

India Currents

Ma’s tadka sizzles before she adds the unmeasured amounts of haldi, jeera, garam masala, kali mirch, dhaniya, and lal mirch to the pan. This technique of cooking down the spice is unique to South Asian cooking and good for health, Ma claims. I ask her, “How much of each spice?” She responds, “What do you mean? Just a few pinches of everything like we always do. Don’t worry, just make it to your taste.” Oh boy, this is only the first step of many and I’m already unclear of the instructions! How am I going to replicate her dish?

Like many natives of India, Kashmiri-Punjabi Aditya Satija settled for the arid climate and golden landscape of Palo Alto, California, when he moved to the US. Having grown up in Mumbai, Satija was accustomed to regularly eating Indian food. When he arrived to attend Stanford University in 2012 at the age of 23, he hadn’t cooked a meal in his life, and he was not about to start then. Learning to cook an Indian meal seemed nearly impossible and cleaning dishes was a hefty chore.

“I chose to eat at the dining hall rather than at home,” he says. He chose items he felt were nutritious, attempting to emulate the traditional Indian thali (plate). “I almost always got bread (roti), a slow-cooked meat (protein/dal), and then a lot of uncooked vegetables and cooked vegetables (sabzi).” Still, Satija gained weight and felt his health decline.

Satija had stumbled into a common habit of the South Asian diaspora: He had abandoned his native diet.

“Don’t eat anything your great-grandmother wouldn’t recognize as food,” advises Michael Pollan, professor of Science and Environmental Journalism at UC Berkeley and author of In Defense of Food: An Eater’s Manifesto.

In a globalizing economy, where everyone has access to an assortment of foods, it can be arduous to follow Pollan’s advice. For immigrants in a new world, the question becomes: What did our great-grandmother eat? And can we make it?

The South Asian ancestral diet is vastly different from the American diet. Its merits are not well-researched nor fully understood, even in the lands from which they originate.

Look at the diet and health trends in India. A 2015 study in the Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research, found that Mangalorean boys around the age of 13 were overweight because of fast food consumption and lack of education about nutrition and diet. A review of health literature in 2016 by the International Journal of Community Medicine and Public Health cited adult obesity, hypertension, kidney and liver, and other medical issues, as the byproducts of the growing western snacks and fast food industry in India.

South Asians in the US carry on the same dietary habits. South Asian Americans are at higher risks for heart-related ailments and diabetes compared to other racial groups, according to a 2020 review of studies in the Washington Post. Nutrition, combined with a genetic predisposition for diabetes and high blood pressure, is the reason that 60% of all heart disease cases in the world are attributed to South Asians.

Here is what is happening: Altering and adapting ancestral eating habits is a survival mechanism for everyone in a globalized economy, especially immigrants to a new country. One result is that generations of knowledge about diet, which are carried out through quotidian habits, become forgotten history.

Satija’s experience is typical for South Asians in the US. South Asian immigrants don’t have access to culturally competent education on the impact of diet on their health.

“There is surprisingly little on South Asian health in US health guidelines, evidence-based recommendations, or even in the general clinical trials literature,” writes Dr. Omar Khan in a review for the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine. He notes that the term “South Asian” is not well-understood by others and that comprehensive research cannot be conducted on populations who are not designated as their own demographic.

Aditya Satija at Stanford.

The Desi Gut Biome

Months into his studies at Stanford, Satija saw that he had to take action. “I was not very aware or careful about the things in my body until I was an adult,” Satija recalls. “That was when I started to notice the changes in my body and health.” He headed to the gym to do pull-ups, an exercise he had done lots of times before. He couldn’t do one.

He found a trainer, who said, “Your arms are not weak. Your body is heavy.” The trainer referred Satija to a nutritionist. However, Satija was hardly set up for success: “My first nutritionist, who was [not South Asian], couldn’t understand why I was eating what I ate. She told me to eat salad. I wasn’t going to eat salad. I’d never eaten salad on its own in my life!”

Then, Satija was referred to another nutritionist — Dr. Sanjana Patel.

“When we first met, she asked me the basic questions of what I ate for breakfast. After assessing, she said, ‘Okay Addy, you clearly have a modern, western diet. Is this what you grew up eating?’ — Which was a question my previous nutritionist had never asked me.”

She introduced Satija to the gut biome, and further explained that the microorganisms that live in his small and large intestine – a live concoction of bacteria, fungi, parasites, and viruses – play a key role in his ability to process certain foods. Satija’s gut microbiota, or the microorganisms living in the digestive tract, developed based on the food he ate as a child and his ethnic background.

Studies show that the gut biome differs among a cross-section of ethnic groups in the same geographic region. South Asian and Caucasian infants in Canada have a gut biome that, prior to the introduction of external influences, is determined by ancestry. As an adult, this coded information reacts to its environment, as seen in a study of Hmong and Karen immigrants to the US. Both populations are subjected to a loss of gut microbiome diversity and function after immigrating to the US, resulting in obesity across generations.

As an immigrant of South Asian descent, Satija was eating the wrong foods for his gut biome. “A lot of this food [you are now eating], your system is not used to,” Dr. Patel told him.

What Desi Americans Should Eat

Vijaya Parameswaran’s healthy plate: moong dal dosa, shalgam sabzi on the right, and cauliflower sabzi on the left.

“Desi grocery stores anchor you, ethnically, to where you were raised and what you have access to,” says Vijaya Parameswaran, a clinical dietician and social science researcher at Stanford Medicine, who for 18 years has been studying the nutritional knowledge gap in the Bay Area’s South Asian community. She stresses the important role that ethnic grocery stores play in South Asian health. “Nutritionally, the value of eating foods that we have been raised with – those that our colonic gut bacteria have been exposed to and enjoy — is really important to [South Asian] health,” She focuses her efforts on South Asian health research and has collaborated with El Camino Health’s South Asian Heart Center, and Stanford South Asian Translational Heart Initiative (SSATHI) – one of the few programs in the country working to understand South Asian American health.

Esha Tiwari, a certified precision nutritionist and wellness coach in the Bay Area, supports that message. “There is a reason why [South Asians] can’t process some foods,” she says. “[They] should go back to their roots! There is memory [of our ancestral diet] at a cellular level.”

Back in India, though, the influence of globalized food production and marketing has influenced native diets. For example, the mass production of wheat in Punjab and the consumption of a homogenous grain in the region, has Punjabis clocking in with the highest incidences of Celiac disease in the world. The use of wheat and rice as the mainstream grain in South Asian meals has decreased the diversity within the gut biome.

That’s a big change from the nutritional profile of food intake in India.

“We [have], as a culture, led in the creative use of lentils, grains, and spices,” Parameswaran says of South Asians over the decades. Her research led her to what may seem like a self-evident verdict: “Go back to eating what you grew up with.”

Parameswaran pushes for the use of indigenous ancient grains: red rice — great for blood glucose regulation and has a better fiber profile; jowar (sorghum) — improves heart health and controls blood sugar levels; bajra (pearl millet) — abundant in magnesium and helps with heart health; and rajgira (amaranth) — a good source of iron and calcium. All of these ancient grains have phenomenal nutrient profiles and were in copious use in South Asia before the mass production of grains.

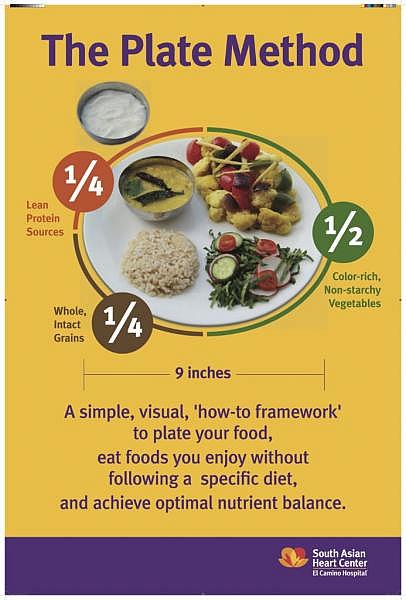

Prajakta Waingankar, Heart Health Coaching Coordinator and Nutritionist at the South Asian Heart Center, directs me to “The Plate Method,” a strategy endorsed by the U.S. Center for Disease Control and Prevention and the American Diabetes Association. She emphasizes the common misconceptions South Asian Americans make.

“In a typical South Asian household, meals are grain-heavy with some protein and not enough non-starchy vegetables. There is nothing wrong with grains — but when it becomes the main part of the entree, then it could result in an excess energy intake and in the long run, increase the risk of high blood sugar or triglycerides. The Plate Method allows you to eat and enjoy your traditional foods without following a specific diet and to achieve optimum nutrient balance. The focus is on non-starchy vegetables which are cardio-protective, low in simple carbohydrates, and high in fiber, lean proteins, and micro-nutrients.”

More importantly, she shares a sentiment similar to Pollan’s: Know what you’re putting in your body. India Current’s Desi Grocery Store Survey found that 45% of people entering the store were buying snacks, sweets, frozen goods, or prepared foods. Both Waingankar and Parameswaran advise shoppers to veer away from such items. Desi shoppers should, instead, head towards the fresh non-starchy vegetables, rainbow-colored dals, and the numerous ancient grains.

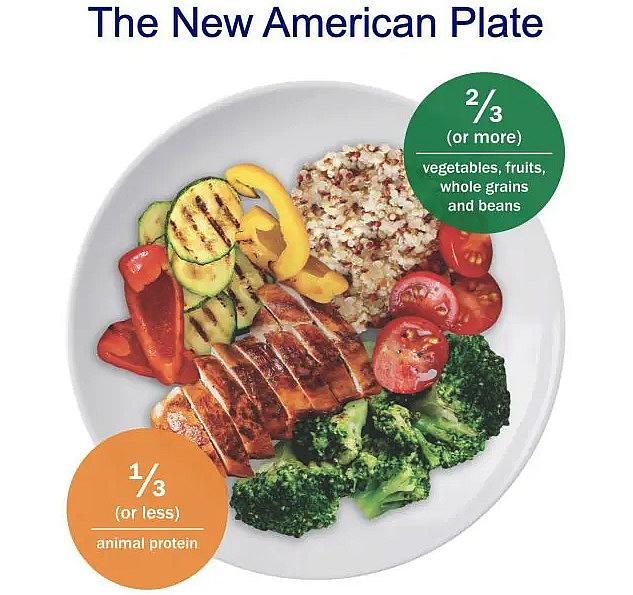

Differences in nutrition guidelines for American and Indian diets. Differences in nutrition guidelines for American and Indian diets.

A side-by-side comparison of a South Asian Plate Method vetted by the South Asian Heart Center and the New American Plate Method endorsed by the American Institute for Cancer Research depicts the variable diets in both cultures. Nutrition, health, and longevity of disparate ethnic races rely on culturally competent research and education.

So what is in the South Asian ancestral diet? The answer can be found at Trinethra on Pearl Avenue in San Jose.

A Thali Assembled at the Grocery Store

San Jose resident Vinu Thyagrajan shopping for groceries at Trinethra on Pearl Avenue.

Tamilian-American Vinu Thyagarajan shops for ingredients to make her Chennai-based dishes. Her list includes: raw mango, mooli (daikon), bangaluru kathrikai (chayote), Indian eggplant, cabbage, lime, coconut, toori (smooth gourd), moong dal, bhindi (okra), sesame oil, mango pulp, green chili, arbi (taro root), winter melon, carrot, pickle, tomato, ginger, yellow onion, red onion, cilantro, yogurt.

She eyes the yogurt and laughs, “If it were up to me, I could eat yogurt, pickle, and rice every day but both my kids are coming home for Golu this week, so I’m making all of their favorite [Tamilian] dishes.”

At the same store, Bihari-American Rita Kumar’s ingredients are different. Her basket includes ghee, frozen peas, jaggery powder, gobhi (cauliflower), lime, bandh gobhi (cabbage), bhindi (okra), kadu (opo squash), panch foran (5 spice), haree sem (green beans), baigan (indian eggplant), dhaniya (coriander), tomato, onion, aloo (potato), paneer, sattu flour, mustard seed, moong dal, multiflour grains, manna kodo millet, foxtail millet, and masala mixes.

She notes, “I’m not buying as many ingredients lately because both of my kids recently left the house.”

Both mothers are at the Desi grocery store, seeking their ancestral foods, hoping to impart some of their knowledge to their children. The variety of fresh produce, spices, dals, grains provided by such stores is essential for a healthy South Asian community. “I never really critically thought about my health,” Satija says. “But once I did, the Desi grocery stores near me were essential to my diet.”

Items in Vinu Thyagrajan’s cart. Items in Rita Kumar’s cart.

Thyagarajan and Kumar’s shopping carts may hold some similar ingredients, but the dishes they make using those ingredients showcase the diversity of diets in South Asian culture.

Thyagrajan’s staples create dishes like: pachadi, sambhar, kurumb, medhu vada, poriyal, adai dosa, Tamilian fish, rasam, kutu, and varuval.

Kumar’s staples are used to make: rajma, chhole, dal, pulao, aloo gobhi, kadhi, kichdi, kheer, bhartha, bhindi masala, aloo baigan, palak paneer, biryani, litti, Bihari fish, halwa, and raita.

Tiwari addresses the gut biome’s evolution propelled by the disparate diets in India. In the Northeast part of India, Biharis use of the sattu – a flour with a mix of gram, pulses, and cereals – is a high source of protein in dishes like litti chokha or sattu bhara paratha, and the Bihari gut biome is more well adapted to digesting this dense flour. In the southern part of India, Keralites eat kanji, dosa, idli, uttapam as part of their daily diet. All are fermented, their gut biome has a higher affinity for fermented foods than does the average Indian.

Trinethra has become the hub for finding ingredients crucial to the South Asian ancestral diet. What the mothers do intuitively, though, requires thought by their children and future generations. The Desi grocery stores provide goods that can ensure the health of their community — if people know what to look for.

“Those who forget the value of the Desi grocery stores [in Santa Clara County] should come live in New Orleans where Desi groceries are inaccessible,” Satija proffers after moving to Louisiana. Santa Clara County’s Desi grocery stores provide space to build physical health, mental health, and ensure that the Desi gut microbiota are healthy and happy!

The spices release a flavorful aroma that permeates and finds its way into every crevice, clinging to hair, clothes, blankets, and curtains. These smells remind me of my mother, my family in India, and leaves my mouth watering. My body has a visceral need for these foods and I worry about, inevitably, having to someday figure out the recipes without my mother.

Rajma Recipe (Bihari Style) From My Mother (Madhavi Prabha)

Why Rajma?

Nutritionist Tiwari recommends Rajma because it is high in protein, calcium, and easily digestible. It is necessary that these beans are soaked for 8 hours because that is how the lentil releases phytic acid. If phytic acid remains in the bean, it will hinder the absorption of iron, calcium, and several other vitamins by the gut.

Rajma (Kidney Bean Dal)

Prep Time: 11-15 minutes

Cook time: 21-25 minutes

Serves: 4

Nutrition Info

Calories: 1462 kcal

Carbohydrates: 176.4 gm

Protein: 48.2 gm

Fat: 62.8 gm

Ingredients

- 1 cup Kidney beans soaked overnight

- Salt to taste

- 4 tablespoons oil

- 1 tablespoon of ghee

- 2 medium Onions finely chopped

- 2 tablespoons Ginger-garlic paste/finely grated

- 2 teaspoons Coriander powder

- 1 teaspoon Cumin powder

- ½ teaspoon Black pepper powder

- 1 teaspoon Turmeric

- ½ teaspoon Red chili powder

- 2 big or 3 small tomatoes finely chopped /1/2 cup Tomato puree

- 1 1/2 teaspoons Garam masala powder

- 1 tablespoon Fresh coriander leaves chopped

- 1 teaspoon chaat masala

Directions

- Drain kidney beans and wash in fresh water.

- Put kidney beans into a pressure cooker.

- Add water to a level slightly higher than submerged, add salt and cook under pressure till 4-5 whistles are given out. Instead of the pressure cooker, you can cook in a covered pot. It will take around 30-45 minutes.

- Drain and reserve the cooking liquid. Heat oil and butter in a non-stick pan. Add onions and sauté till light brown.

- Add ginger-garlic paste and sauté for 2 minutes. Add coriander powder, cumin powder, turmeric powder, black pepper powder, and red chili powder and mix well

- Add tomato puree and mix again. Sauté for 3-4 minutes.

Instead of the puree, you can add finely cut tomato if you want

- Add kidney beans and mix well. Add 1 cup cooking liquor and salt and stir to mix.

- Mash the beans a bit and stir again. Add garam masala powder and mix and cook for 5-7 minutes.

- The purpose of mashing is to merely soften the rajma. Do not turn it into a paste.

- Add chaat masala and mix well.

- Garnish with coriander leaves and serve hot.

This article was produced as a project for the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2021 California Fellowship.

[This article was originally published by India Currents.]