Growing up through the cracks: Policing change brings cops up close with kids in poverty

Michael M. Santiago/Post-Gazette

By Lacretia Wimbley

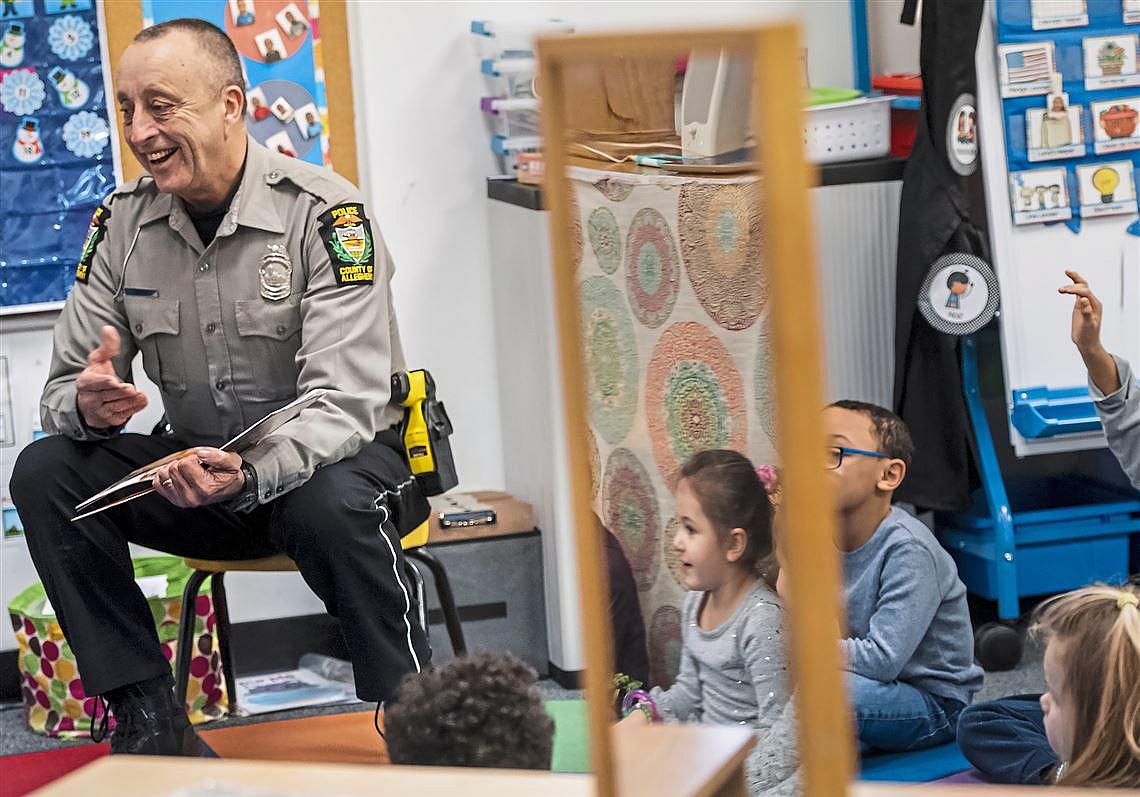

“Thank you, Officer Joe!” said some half-dozen preschool students in appreciation as Officer Joe Risher completed reading “Five little kittens” by Nancy Jewell.

In the tiny classroom — colorfully decorated with a large rug, books and snowmen and snowflakes — the young students had giggled and looked intently as Officer Risher animatedly read the story of a mother cat taking care of her young kittens, at the East Allegheny Family Center on Westinghouse Avenue in Wilmerding.

“Thank you for letting me come to your circle. Can we do it again?” Allegheny County Police Officer Risher asked the group of excited children.

“No,” one child joked with a smile. “What!” said Officer Risher, with a sarcastic look of shock on his face.

“Yeaaahhhh!” the children all said in unison, giggling and squirming about for the familiar visitor.

“I just wanted to establish a relationship with the kids here, because there would be times when I would have to go into their homes, which has happened here, you know, getting domestic violence calls,” Officer Risher said later. “I wanted to be a familiar face.”

Policing is often a big challenge in communities, like Wilmerding, that face concentrated child poverty. Those communities often have anemic tax bases, making it hard to pay police, and high public safety demands, spurred by desperation, transience, abandoned buildings and mental health and other human service problems.

In its ongoing series Growing up through the Cracks, the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette is focusing on southwestern Pennsylvania communities in which around half of children live in poverty — a problem that's hard to address in a region with fragmented governance and limited sharing of resources across municipal boundaries.

Today: A police perspective.

Wilmerding is the only municipality to pursue an unusual arrangement with Allegheny County to shore up public safety for its residents.

The North Versailles Police Department patrolled Wilmerding from 1999 to 2016. Effective on Jan. 1, 2017, the small borough of roughly 1,996 residents signed a five-year contract with Allegheny County, agreeing to pay $250,000 each year, plus 25 percent of the amount paid to the borough for fines issued by county police during the prior year. After the first year, the base payment increases by 3 percent each year.

"Some people felt the community was going downhill, and older people had something like a hopelessness about their community," said Maurita Bryant, assistant superintendent for the Allegheny County Police Department. "The community didn't really have bad crime, but they had little fights here and there. People were smoking and drinking on corners, and they had a few break-ins."

Wilmerding is one of seven Allegheny County municipalities of significant size in which around half of the kids live in poverty. Those seven are among a dozen such municipalities in the region which the Post-Gazette is exploring this year.

In Wilmerding, 36 percent of people were living in poverty between 2013 and 2017, according to the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey, but one's likelihood of being in poverty was closely associated with age.

Sixty percent of children who were under the age of 18 were living in poverty, four times the countywide rate and far higher than other age groups in Wilmerding. Roughly 20 percent of people 65 and older were in poverty, as were around 29 percent of people aged 18 to 64.

Officer Risher has witnessed the way economic hardship, poor housing stock and childhood trauma intersect.

“When you talk about poverty and the conditions kids have lived in in this town,” the environments police encounter can be “sad,” said Officer Risher. “I actually went into one home and arrested the mom; we had the grandparents come get the kids and the kids were taken off of them. We had the house condemned that day, and when dad came home from work, he got arrested too.”

Officer Risher said this happened during Allegheny County’s first year patrolling Wilmerding, when the East Allegheny School District nurse requested a wellness check, concerned about three siblings who hadn’t been seen at school in a week.

“So we go out there, the kids are home, and the conditions were absolute filth,” he said. Bugs, food waste, mold and a dirty tub made it clear to him that he needed to make an arrest and remove the kids.

Several hearings and classes later, Officer Risher said the parents were able to get their children back, and had cleaned the house to an acceptable standard, following court stipulations of random checks from police.

While poverty is a reality for a majority of Wilmerding’s kids, the borough is also “a nice knit community,” said Lavette Smith, a mother of three teenage boys who owns the Dreamers & Achievers Childcare and Preschool in Wilmerding and Pitcairn. “As far as poverty is concerned, and from my perspective, I don't see anything major that they can't do with hard work and compassion.”

“Here, I just see that the people are very nice,” said Mrs. Smith, 48. So are the police, she said. “Officers have randomly donated items to the daycare during Christmas, which was really kind.”

Not everyone has had a positive view of the officers’ presence in the community.

“Some of the people we had trouble with our first year, we don’t seem to have trouble with them anymore,” said Inspector Chris Kearns of the Allegheny County Police, who works in Wilmerding. “Kids complain and parents sometimes complain about us, saying we pick on them. We had a good four or five people that were, every time something came up, it was them who were in trouble. But we haven’t heard much from them lately.”

Assistant Superintendent Bryant said the community has become transient, with older residents dying and slum landlords refusing to maintain certain properties. Wilmerding has seen around a 10 percent decrease in population since 2010.

“It takes resources and it takes people in the community to not give up, so they can keep the community the way they want it to be,” she said.

To establish trust among the youth, and to ensure kids who may be in trouble are aware of their safety net, Officer Risher said building relationships with children in the community is critical. Since August, he works as the crime prevention and community relations officer, visiting schools countywide, but for now, he still visits the East Allegheny Family Center every other Tuesday.

“I’d be on a traffic stop checking for a driver’s license, and talking to them and a car would go around me and I’d hear out of the back seat, ‘Hi, Officer Joe!’” he said. “The kids will recognize me, and they’ll recognize me a year or two later in Walmart or wherever. A relationship with the police in early childhood education is important.”

Lacretia Wimbley: 412-263-1510, lwimbley@post-gazette.com or follow @Wimbleyjourno on Twitter. This story was produced with assistance from the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s Data Fellowship.

[This article was originally published by the Post-Gazette.]