The impact of an aging population: a growing need for memory care as the Central Coast ages

This is the third story in a series reported as a project for the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism 2021 Data Fellowship.

Other stories in this story include:

Part 1: The impact of an aging population on Central Coast health care and health care workers

Part 2: The impact of an aging population: nurse shortages on the Central Coast

The Adult Day Center in Paso Robles is a place for adults with memory loss to safely spend daytime hours.

Beth Thornton

In the coming years, the Baby Boomer generation will be aged 65 and over, and as health care needs increase, more resources for adults with diseases like Alzheimer’s and dementia will be needed on the Central Coast.

The Adult Day Center in Paso Robles is a cozy house from the 1930s where seniors with memory loss can safely spend their daytime hours. Lunch is provided and the seniors engage in supervised activities.

“We do a daily chronicle which is news from the past, we reminisce about history, we talk about positive things that are going on and hopefully spark some memories of things that they’ve done,” Mara Whitten said.

Whitten is the program manager for the Community Action Partnership (CAPSLO) Adult Day Center. She said the individuals who come there have memory loss conditions like Alzheimer’s or dementia. The center is not a medical facility, but a place where families can bring their loved ones during the day.

“Maybe it’s not safe to be home by themselves, or it’s for that person to be able to socialize in a safe space. For those that are working, that’s a big issue,” Whitten said.

Michele Walker’s husband Dan goes to the Adult Day Center twice a week. He has short-term memory loss from an aneurysm and stroke suffered two and a half years ago, and at 71 years old, she thinks he’s one of the youngest clients at the center.

“It can be a devastating blow, we never thought this would happen. Your lives do change, and you learn to live in the moment,” Walker said.

She said doctors don’t know if Dan’s symptoms will get worse, she’s been told he might develop Alzheimer’s, but for now, she said he communicates well and does many daily tasks on his own.

He is independent enough to take the bus from San Luis Obispo to the Adult Day Center in Paso Robles. And while he’s there, Walker said she visits with friends and attends caregiver support groups. But mostly, she said, the two of them stay close to home.

“Last year, our grandchildren were out of school and we took them out to lunch in San Luis, and Dan said to me, ‘I need to go to the bathroom,’ and I said, I’ll get up, and he said, ‘no, look, the sign is right there’,” she said.

She said the door marked ‘restroom’ was in clear sight of where they were seated, so he went on his own.

“Ten minutes later Dan hadn’t come back, and there were two bathrooms but there were nine other doors that led to different buildings, and then there were outside doors,” Walker said.

Realizing Dan was lost, she called the cell phone he keeps in his pocket at all times. She said his ability to operate the phone is limited but he did answer her incoming call.

Walker said she’s fortunate that her husband’s memory loss is relatively mild, and that scary moments like the one at the restaurant are rare.

As the population ages, it’s likely that many people will find themselves in a similar position as Walker, caring for a family member with memory loss.

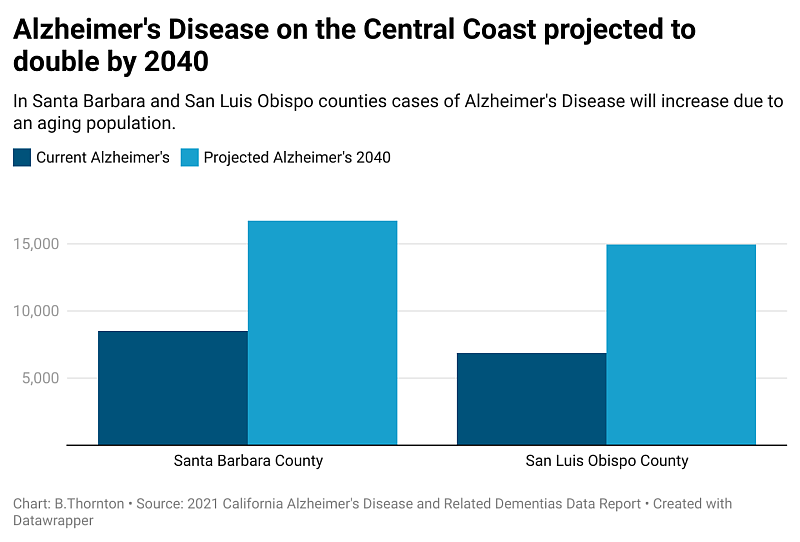

The California Department of Public Health projects that 1.6 million residents will have Alzheimer’s disease by 2040. The number projected for Santa Barbara and San Luis Obispo counties combined totals about 32,000.

Beth Thornton /

Kathryn Cherkas, program director for the Central Coast Chapter of the Alzheimer’s Association, said dementia and Alzheimer’s disease are not a normal part of aging, but the number one risk factor is being over the age of 65.

In California, about 1 in 5 adults will be 65 or over by the year 2030 according to the Public Policy Institute of California. On the Central Coast, the percentage of the population over 65 is higher than the state average, and in some places it will be closer to 1 in 4.

Cherkas said we need to prepare.

“We are a little resource-low in terms of geriatricians, physicians that specialize in older adults,” she said.

The state of California also forecasts a shortage of geriatricians by 2040. The Central Coast currently has fewer than 25 licensed geriatric specialists within Santa Barbara and San Luis Obispo counties according to the California Medical Board.

But it’s not just traditional healthcare services that will be affected by this demographic shift, Cherkas said family members often call 911 for help, especially when a loved one goes missing. She said dementia symptoms like confusion and fear can result in difficult encounters. With this in mind, she is forging relationships with local police departments.

“I think this is a very important relationship that’s not only beneficial but essential,” she said.

Cherkas recently trained about 50 police officers in Santa Barbara.

Sergeant Ethan Ragsdale is the public information officer for the Santa Barbara Police Department.

“Those officers that were trained are primarily patrol officers that are out in the field responding to 911 calls that come in through our dispatch center,” he said.

Ragsdale described the training as eye-opening and important given the changing demographics.

“I can absolutely imagine that there are going to be more medically-related calls for service coming in through our dispatch for fire and paramedics to respond to, and same with police calls for service,” he said.

Ragsdale said the department recently added a co-response team that pairs a certified therapist with a patrol officer to better respond to mental health emergencies. He said expanding this approach for dementia-related calls could help going forward.

Cherkas from the local Alzheimer’s Association said, at this point, there’s no cure for the disease and with the aging population on the Central Coast, it’s time for individuals and the community to make a plan.

“We know the trajectory, we know the numbers of adults that are the age of risk. We know it,” she said.

Education and awareness, she said, as well as additional resources will be key to managing what’s ahead.

This is the third story in a series reported as a project for the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism 2021 Data Fellowship.

[This article was originally published by KCBX.]