The impact of an aging population: nurse shortages on the Central Coast

This is the second story in a series reported as a project for the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism 2021 Data Fellowship.

Other stories in this story include:

Part 1: The impact of an aging population on Central Coast health care and health care workers

Part 3: The impact of an aging population: a growing need for memory care as the Central Coast ages

Cuesta College students in the ADN program for registered nursing

Cuesta College

As the population ages and the baby boomer generation retires, nurse shortages are projected in California and on the Central Coast. This challenge comes on top of the already depleted health care workforce due to the pandemic.

Educating more nurses could help to meet future needs, but it’s not a simple solution.

“Current projections show by 2026, that we’re going to have a shortage of 40,000 RN nurses, so that refers to people that have either an associate’s degree or bachelor’s degree in nursing,” Rehman Attar said.

Attar is director of health care workforce development for the California State University (CSU) system.

He said nurse shortages will vary across California with rural areas, and places with older populations, like the Central Coast, more likely to experience shortages.

“The nurses aren’t there because they’re either retiring, or we’re not producing enough to meet those needs,” he said.

The CSU system has 23 universities. Twenty of those campuses educate nurses and around 4,000 graduate each year.

On the Central Coast, the two large public universities — UC Santa Barbara and Cal Poly San Luis Obispo — do not have nursing programs. Cal Poly SLO is one of the few CSU campuses without a nursing degree. As a polytechnic school, it is different by design, with emphasis on fields like agriculture, engineering and business.

However, Attar said the campus could add a nursing degree in the future if ongoing assessments show a need.

There are online and private options for nurse education, but most students from San Luis Obispo and Santa Barbara counties leave in search of a bachelor degree in nursing, or they earn an associate degree, called an ADN, from a local community college.

Since Cal Poly does not have a program, Attar said other Cal State campuses partner with community colleges in the region to make it easier for nursing students to continue their education.

“We understand that there’s an equity aspect to ensuring access to students and one of the best ways students have had access to higher education has been through their community college and then into a Cal State for a baccalaureate degree,” Attar said.

Cuesta Community College in San Luis Obispo partners with CSU Monterey Bay. Allan Hancock in Santa Maria and Santa Barbara City College partner with CSU Channel Islands.

Marcia Scott, director of nursing at Cuesta College, said a partnership began about five years ago.

“We developed a partnership with CSU Monterey Bay where they [students] begin taking courses while they’re still enrolled in our ADN program and upon graduation, they go fall and spring and they will have their Bachelor of Nursing twelve months later,” Scott explained.

Scott said the hybrid program is designed for students that live and work on the Central Coast.

“To date, we have graduated 80 BSN students in our county through this partnership,” she said.

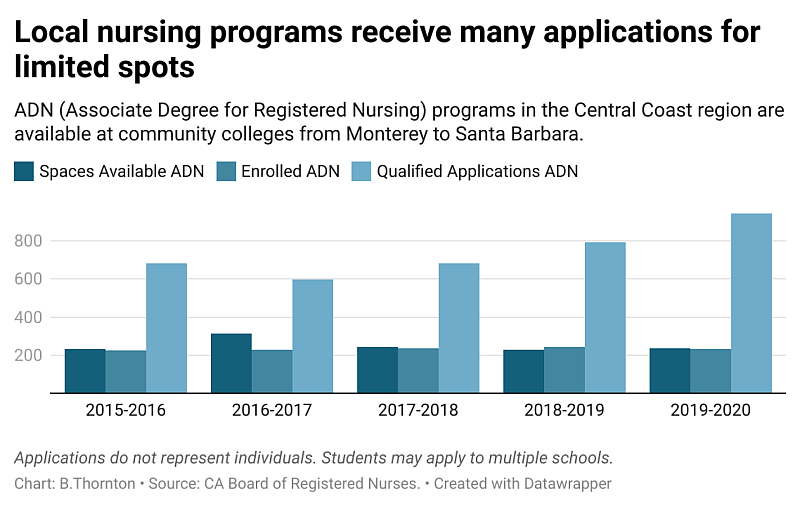

These partnerships are a promising way to grow the local workforce, yet enrollment capacity for nursing at the community college level remains limited.

Cuesta accepts 46 ADN students per semester, while SBCC admits 35-45. Allan Hancock College enrolls 34 students per year as Licensed Vocational Nurses (LVN) and from there, students progress to an ADN degree.

All three nursing programs have high on-time completion rates and high pass rates on the state licensing exam. They also receive far more applications than spots available.

Eileen Donnelly, nurse director for the LVN program at Allan Hancock, said many qualified students apply, but class size is limited.

“We have an average of a 2-4 year waitlist,” she said.

Donnelly said students who complete ADN programs for registered nursing and pass the state boards are in high demand.

“Typically, as soon as they get their RN license, they have a job,” she said.

Admitting more students to local programs could help to grow the workforce, but it’s more complicated than simply expanding class size.

At Santa Barbara City College, Sarah Orr, director and chair of the ADN program, said nurse educators are in short supply.

“We are in big need of full-time and part-time faculty right now. This is a hard place to hire into, it’s a very expensive community,” she said.

Another factor is access to hands-on experience for students. Orr said the pandemic limited training hours in local hospitals and without clinical rotations, students can’t graduate.

Increasing enrollment may not be possible at this time, but Orr believes nurses always come through in times of crises, and they will continue to do so. She also said it’s important to recognize their needs for work/life balance, so we retain the experienced nurses we do have in the field.

“They’ve always been heroes and we need to treat them as such. They need competitive wages. They need not just the money, but the appreciation, the time off,” Orr said.

With shortages looming on the Central Coast, Rehman Attar said CSU will continue to look for innovative ways to share faculty and resources for nurse education.

This is the second in a series of stories for KCBX reported as a project for the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism 2021 Data Fellowship.

[This article was originally published by KCBX.]