For SF’s Homeless, A Permanent Home Is the Ultimate Goal. The Fight Is How to Get There

This story by Kristi Coale, a 2020 Impact Fellow, is part of a larger project investigating San Francisco’s record of caring for its unhoused people during the pandemic.

Her other stories include:

A homeless family in SF lives in housing limbo, while more city-funded apartments sit empty

SF’s Homelessness Department Has a Billion Dollars, and Brings Up Almost as Many Questions

Building Homes for SF’s Homeless Is Hard. Providing Mental Health Care Is Even Harder

SF’s Big Street Count Is Coming Back, But Homelessness Fixes Require Deeper Reform

Will it work in SF? Hoang Nguyen stands in front of his “tiny home” at a San Jose site that gives unhoused people a room of their own while they wait for permanent housing, which is in short supply. San Francisco has an interest in his success, as the city fights over how much to spend on transitional housing like tiny homes while more permanent units are in development.

(Photo: Pamela Gentile)

Last November, Hoang Nguyen closed the door to his own home for the first time in 18 months when he took possession of an 80-square-foot residence near the BART tracks in San Jose. He might not realize it, but a lot of people in San Francisco, about an hour north, have a stake in how things work out for him.

“Being in the room all by myself, it feels good,” says Nguyen, standing on his home’s mini deck.

Nguyen, 59 and single, had always lived with and cared for older relatives and folks he considered family in San Jose. He never paid rent. But when his Vietnamese “grandmother” died in 2018, the landlord noted that Nguyen’s name wasn’t on the lease, and he was evicted.

Unemployed and living on $148 a month in government assistance, Nguyen first turned to an emergency shelter. He worked in the shelter’s kitchen at night while holding down a part-time job at the county fairgrounds, until COVID shut down that venue. Eight months later, the shelter provider HomeFirst Services placed him in a community of 40 tiny homes that had opened in early 2020 near the North San Jose BART station.

Nguyen’s place is spare but cozy. It has a bed, some shelving, a desk and chair. There’s a bike rack mounted on the outside with a blue cruiser donated by a local cycle shop that he rides to his job at a nearby Amazon fulfillment center. Nguyen has built up references that could help him get a subsidized apartment of his own.

A stable, permanent home is what everyone wants, and that’s getting a big push from the unprecedented amount of money from pandemic stimulus. Local and national advocates say now’s the time to build — or even faster, to convert unused hotels into affordable permanent homes.

Nguyen, 59, lived with friends and relatives until a recent eviction. He rides his bike from the tiny home community to his job at a nearby Amazon warehouse. (Photo: Pamela Gentile)

Even with billions more dollars now available, it’s easier said than done, especially in San Francisco. That’s why people on the streets or using overnight shelters often need a transitional or “bridge” step, with security and support, as they rebuild their lives and wait for a permanent spot.

Tiny homes are one option for that transition. In the San Jose program’s first year of operations, half of its 144 residents went on to permanent places. That was good enough for city officials there to open a second site in February, and is why these tiny homes in the South Bay matter to San Francisco. The city’s first tiny home experiment is coming later this year.

But it’s also arriving amid a growing debate: How much of the state and federal windfall should be spent on long-term housing, and how much for stopgaps like tiny homes that might not deliver the ideal results but can deliver some measure of relief more quickly? “There’s a real opportunity here to get people off the streets and into units,” said Nan Roman, president of the National Alliance to End Homelessness.

The debate grew louder this week as one city supervisor’s proposal for more tent sites ran aground after criticism from a top homelessness advocate, echoing tension across the country. “It shouldn’t be a zero-sum game,” said Roman. “But it is.”

The stimulus money won’t last forever, which means in coming months this complex issue will remain front and center as San Franciscans ponder and jostle over the shape of a post-pandemic city.

The tiny home community on Mabury Road, near the North San Jose BART station, has 40 cabins with heating and air conditioning. Half the 144 adult residents in the site’s first year have moved into permanent housing, according to HomeFirst Services, the nonprofit agency that runs the site. (Photo: Pamela Gentile)

Many bridges, one goal

The answer to homelessness is obvious: Get people off the streets and into homes, while making sure those with homes don’t lose them. But obvious is different than simple.

Many people on the streets need housing with health care, counseling, and other services nearby or on-site — what’s known as “permanent supportive housing,” or PSH. Even before the pandemic, San Francisco officials, including Mayor London Breed, emphasized PSH as the primary solution for the homelessness crisis.

Margot Kushel, head of UCSF’s Homelessness and Housing Initiative, and others in the field emphasize that housing is health care. The average life expectancy for an unhoused person is 25 years less than a housed person. “Fifty is the new 75,” Kushel said in an August 2019 podcast.

People on the streets are nearly four times more likely to have substance abuse disorders than people who are housed, and six times more likely to suffer from depression, according to the National Health Care for Homeless Council.

By San Francisco’s last count in 2019, there were 8,000 homeless, 5,000 of whom were unhoused. It was considered an undercount then, and COVID has probably made things worse. The scheduled 2021 count for SF was postponed until next year. (The most recent numbers are from January 2020, when a one-night count of sheltered homeless in California showed a 7% increase over 2019.)

There’s not nearly enough room, or rooms, for folks in need. As of April 22, the city had only 647 empty PSH units. Even if it hits the mayor’s goal of 1,500 more units by 2022 — officials say they’re halfway there — transitional alternatives will be necessary.

It’s also not clear how San Francisco will meet its promise of housing for the roughly 2,000 people who received spots in temporary emergency hotel rooms during the pandemic. (Most of them are still in the hotels; they might not want to leave.)

As the COVID threat recedes, a critical clock is ticking: Eviction moratoriums are winding down, along with the emergency funding that has paid for those emergency shelter-in-place hotels, known as SIPs. “We have to transition 2,000 people in SIPs to permanent supportive housing, and reopen our city — I would hope — without many thousands of people living on the sidewalks,” Sup. Matt Haney told The Frisc in March.

“Transition” is the key term — and the root of the current tension. Five years ago, as sidewalk encampments mushroomed, then-Mayor Ed Lee pledged that the city’s new homelessness department would keep people off the streets by moving them to housing through an interim step: a network of specialized shelters called Navigation Centers that function like halfway houses. Breed has since opened new ones, sometimes over ferocious neighborhood opposition.

These centers had 1,076 beds pre-COVID, though the pandemic temporarily cut capacity in half. Again, that falls short for the people who would prefer privacy and autonomy in their living conditions as they wait for permanent housing.

Note that group or overnight shelters, shuttered due to COVID but now reopened, aren’t the same as transitional housing. In a 2020 study of nearly 600 unhoused San Franciscans, 58 percent actually preferred a spot in a sanctioned tent village over a shelter bed, citing safety fears and work-schedule concerns.

To give people the best chance to reach permanent housing, the city needs more options that offer them greater privacy, stability, and control over their lives. It will also need to watch its wallet, all the more apparent after reports emerged that the sanctioned tent sites cost more than $60,000 in services — including meals, facilities, and security — per person per year.

Standing up, getting dressed

The idea of tiny homes has been around for a while in San Francisco. Homelessness activist Amy Farah Weiss staked her two long-shot mayoral campaigns in 2015 and 2018 on building tiny places but did not gain traction, even as cities like Seattle began to treat them as an important shelter option.

Serious obstacles remain, but momentum from other locations has led, at long last, to a pilot project in SF with 76 cabins, two offices, and a trailer with restrooms and showers. Supporters say several hundred of the cabin-like structures could eventually be part of a menu for people to get off the city’s streets while they wait for a permanent home.

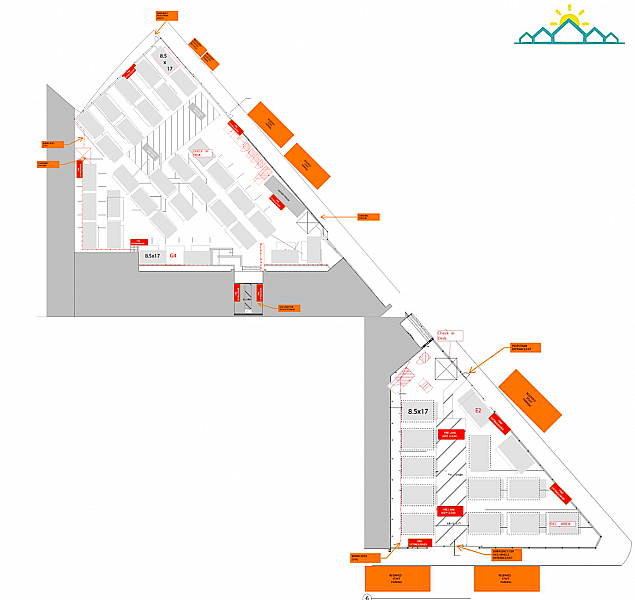

The layout for 76 tiny home cabins across two parking lots at 33 Gough Street. (Courtesy: DignityMoves)

The tiny-home village, spread across two parking lots at 33 Gough Street, will replace an official tent site. The cabins will have electricity and Wi-Fi; each unit will come with a bed, some cabinets, a desk, and a chair. Four will accommodate disabled residents.

Most importantly, each home will have a locking door, which gives people “privacy and the simple dignity of being able to stand up in the morning and get dressed,” says Elizabeth Funk, co-founder of DignityMoves, the nonprofit managing the project. (It will be the group’s second village; the first one is down in Mountain View.)

Funk and colleagues have some lessons to draw from. Early villages in other cities received mixed reviews, with comparisons to shantytowns, with no electricity or heating. An effort in Oakland actually placed people in the same unit with strangers.

In San Jose, HomeFirst Services (which isn’t affiliated with the upcoming SF project) took note and built its tiny homes with heating and cooling. Their two sites include larger “common area” trailers with a computer lab, kitchen, laundry, and showers. There’s even a dog run.

Tiny-home villages are also growing more viable because communities across California are less hostile and relaxing their regulations, as Rebecca Coleman noted in her master’s thesis for the UC Berkeley Department of City and Regional Planning. At the same time, the housing affordability crisis has moved SF and other cities to allow property owners to add accessory dwelling units, aka backyard cottages and “granny flats,” more easily — creating a new market for small, modular housing.

Components for the tiny homes at 33 Gough, made by BOSS Tiny House, will be assembled on-site. Funk estimates the construction costs to be between $15,000 and $18,000 per unit. The site might cut expenses by using sanitation equipment already there from the tent village, but Funk couldn’t say what the total annual cost per resident will be.

Whatever the eventual cost, however, SF taxpayers won’t foot the bill. DignityMoves is raising private funds for most of the pilot, which it says could last two years, depending when an affordable housing project slated for the site breaks ground.

To scale up beyond the 33 Gough experiment, however, the tiny-home model must overcome a few challenges. Even with outside funding, costs remain an issue. Another is labor; city trade unions look askance at prefab housing, which requires less of their work. But the biggest issue for tiny homes in our hilly 47-square-mile city, or any housing project for that matter, is location. “You still need a flat, sizable parking lot. There’s a very small number of sites where you can put these,” says Rebecca Foster, CEO of the Housing Accelerator Fund. (A few years ago, a permanent prefab project on César Chávez Street would have added up to 200 tiny units to the city’s housing stock, but hit snags over labor and land issues.)

Lack of space has already proved problematic for something similar. Instead of tiny homes, the city wants to open a second “vehicle triage center,” where people living in cars and RVs can park safely. The first vehicle center, with about 30 parking spaces, was near the Balboa Park BART station but closed in mid-March to make way for affordable housing. There’s no replacement site yet. “Even in our district, it was hard to find a surface parking lot,” District 11 Sup. Ahsha Safaí tells The Frisc.

Cost-effective cars

Private vehicles are serving as shelters of last resort, at least as long as there are places to park. When San Francisco’s unhoused population exploded between 2017 and 2019, 68 percent of the increase came from people living out of their cars.

The same 2020 study cited above of unhoused San Franciscans, from the Coalition on Homelessness and the UC Berkeley School of Public Health, reported that it’s easier to rehouse people living in cars, yet they’re not usually prioritized for housing and have few services available to them.

The city, in fact, was already doing this. In November 2019, it launched the vehicle triage center, and the experiment worked out by one important measure: Twenty-four of the 55 households it served — 44 percent — moved into permanent housing, according to the SF Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing, which uses the term households to describe both multiperson groups and individuals.

An aide to Safaí called the results “overwhelmingly positive and cost-effective.” The supervisor wants to expand the program at what he estimates would be $23,000 per parking spot, money well spent since the people in these sites are more easily transitioned into housing. “They’re not hard-core homeless,” adds Safaí. “A lot of them are there because they’re not able to afford high rents and they’re looking for a cheaper alternative.”

(When the pandemic struck, an emergency site in the Bayview for 120 recreational vehicles also sprang up, which the city ended up sanctioning. There are no data on exits to permanent housing from this site.)

Safaí believes the minimum number of spots to make vehicle-based shelter work would be 250 across several sites, for about 500 people: “Wherever you’re going to do this, you need to be able to maximize opportunity and minimize costs.”

This week, he got backing from a committee that oversees a chunk of SF’s homelessness budget that comes from the Proposition C business tax. The committee recommended adding at least $10 million for the Bayview site to the next two-year city budget.

The committee was much less enthusiastic about the idea of more sanctioned tent sites, however.

I am disappointed that the Budget and Finance Committee shelved my “A Place for All” legislation today. I believe “A Place for All” aligns with the values and sensibilities of a majority of San Franciscans... https://t.co/YoPHdjrENj 1/3

— Rafael Mandelman (@RafaelMandelman) April 21, 2021

The criticism tanked a bill that aimed to expand the city’s tent sites, sponsored by Sup. Rafael Mandelman, who revived it despite the surprising costs revealed recently. The opposition came most notably from Jennifer Friedenbach, executive director of the Coalition on Homelessness and a member of the Prop C oversight committee. Cost was one objection, underscoring the tension between permanent housing and temporary shelter as a budget priority. She said the bill would give officials a green light to “warehouse” people and would make homelessness worse. (Friedenbach’s organization was the sponsor of the survey in which 58% of homeless people said they would prefer a sanctioned tent site to an overnight shelter bed.)

Not one size fits all

It’s worth repeating: Permanent housing, the more stable and supportive the better, is the best way to keep chronically homeless people off the streets. “There’s decades of trauma that need lots of intensive clinical support” including addiction counseling, treatment, and psychiatric care, says Sara Shortt of the Community Housing Program. Without these services, it’s hard to keep people in housing once they get it.

The city’s nascent Mental Health SF program, which just hired its first director, is focusing on the chronic population and will include supportive housing units among its substance abuse and mental health treatment programs.

But while Mandelman’s bill has been put on hold, the larger point he made was important: We need alternatives for the thousands of unhoused people who won’t be moving into permanent housing anytime soon. For them and for their housed neighbors, we shouldn’t settle for sidewalk camps and their accompanying hazards.

And as we consider and debate the alternatives, whether they’re tiny homes or cars or temporary hotel rooms or Navigation Centers, another point is also crucial: The unhoused are not a monolithic population. Some have been homeless for years and won’t be able to stay in housing without help. Others have jobs, but can’t afford their rent or somehow fall through the cracks.

No one solution fits all. The city tested “safe parking lots” and liked the results. It should be open to other experiments as well. For folks like Hoang Nguyen in San Jose, a chance for a room of one’s own at a crucial time can make a big difference.

Kristi Coale (@unazurda) is a San Francisco-based freelance writer and radio producer for various outlets, including KALW’s Crosscurrents and the National Radio Project’s Making Contact. She reported this story as a USC AnnenbergCenter for Health Journalism 2020 Impact Fund Fellow.

[This story was originally published by The Frisc.]