Shot in the face as a young cop, Milwaukee County's sheriff-elect knows how hard it is to heal from trauma

James E. Causey’s reporting on this project was completed with the support of a USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism grant.

Other stories in this series include:

I returned to the 53206 neighborhood — and saw some boys turn into men

Want to get involved in a community garden? It's not all weed-pulling.

How a Milwaukee community garden helped turn a struggling boy into 'Lil Obama'

Milwaukee couple make it their mission to give trauma victims the chance to talk and be heard

A reporter shares lessons from a Milwaukee garden trying to save at-risk boys

In Milwaukee's poorest ZIP code, fruits and vegetables become powerful weapons for saving young boys

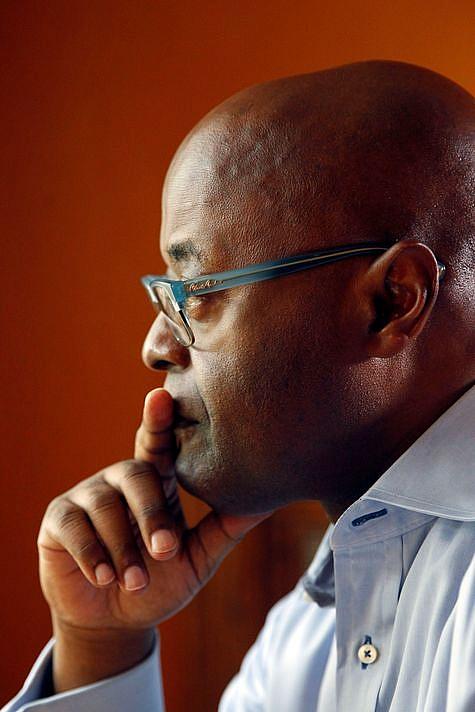

Earnell Lucas, Milwaukee County sheriff-elect.

(Photo Credit: Angela Peterson/Milwaukee Journal Sentinel)

Earnell Lucas is approaching a milestone date.

On Jan. 7, he will become Milwaukee County sheriff, the 65th person — and third African-American — to hold the post. In the meantime, he has been doing a lot of thinking about other key dates in his career.

July 29, 1979: Sworn in as a Milwaukee police officer.

Jan. 5, 1992: Elevated to sergeant.

March 7, 1999: Promoted to captain.

There are other dates, of course: When he was hired by Major League Baseball as supervisor of security (Jan. 22, 2002). When he launched his campaign for sheriff (March 28, 2017) and election night (Nov. 6, 2018), when he won overwhelmingly.

Then there is Jan. 1, 1982.

That was the day Lucas, then a 23-year-old police officer, was shot in the face while responding to a routine call.

That experience, and the slow recovery that followed, helped shape his approach to law enforcement — understanding the difficulties officers face on the community's dangerous streets, as well as the difficulties faced by residents who live there.

"I'm certainly one who knows and understands the dangers an officer faces when they place their badge over their heart and leave their home to serve and protect our community," said Lucas, 60.

* * *

Today, nearly 37 years later, the call seems exceptionally ordinary: Investigate a noise complaint from a resident at an apartment building at North 10th and West Walnut streets.

“It may be the most routine call that any officer can go to,” Lucas said.

It was 6:30 a.m. on New Year’s Day 1982.

When Lucas arrived with his partner, Gregory Moore, 24, they were met by a woman who lived on the second floor of the building. She told them that the man in the apartment below, Henry Damron, was making a lot of noise.

When Lucas and Moore stepped to his door, the only thing they could hear was the TV and an exhaust fan.

“We knocked, and he wouldn’t let us in," Lucas said. "I was trying to create dialogue with him when we heard him fall inside the apartment and we lost communication.”

Now concerned for the man's health, Lucas got the apartment manager to give them a key to open the door. Inside, they found Damron, 75, seated in the middle of the floor with a 12-gauge shotgun pointed at the door.

“I was trapped behind the door and my partner was behind the wall," Lucas said. "I got Gregory to call for backup and we waited for additional help.”

Moments later, the woman who made the original call started coming back down the flight of stairs. Fearing for her safety, Lucas stepped from behind his cover to stop her.

“The only words I could say were ‘Lady don’t,' " Lucas said.

The man fired one round, striking Lucas in the right side of his face. The blast sent him backward and through the building's main entrance.

"It spun me around into a foot of snow,” he said.

His partner radioed for help: Officer down.

* * *

The January 2, 1982 edition of The Milwaukee Sentinel displays an article about Earnell Lucas. Lucas, then a Milwaukee police officer, was shot while responding to a noise complaint. (Photo: Milwaukee Journal Sentinel files)

Lucas was raised by his grandmother, who moved to Milwaukee in 1969 after his mother died. Lucas was 11 at the time. He had two brothers — 13 and 15.

The boys had a relationship with their father, but he did not live with them.

His grandmother, 68, was a "domestic" from Jasper, Ala. That is, she worked for white people, tending to their ironing, cooking and cleaning.

“Grandma was a praying grandma,” Lucas said. “She was a tough old lady."

She sold her home and everything she had to move to Milwaukee and raise Lucas and his brothers. She promised them she would stay until they all finished high school, but gave them plenty of room to make their own decisions.

“My grandmother didn’t drive a car or have a driver’s license,” he said. “She made it very clear to us that we could go do what we wanted to do, but we were responsible.”

Weeks after Lucas got his diploma from Rufus King, his grandmother packed up and moved back to Alabama. It was July 5, 1976.

“I had less than a month to figure out what I was going to be doing in this life,” he said.

Lucas, then 18, had two possibilities: He had applied for the Educational Opportunity Program at Marquette University for first-generation minority college students. And he had applied to be a police aide.

That was the path he chose.

He was inspired to become a police officer by what happened one day when he was 12. It was an encounter with a police officer that could have gone wrong.

That day, his grandmother had given him a note and sent him down the block to Russell's Food Store, 101 E. Burleigh St., to pick up sugar, milk and her favorite — Pineapple Orange Hi-C.

A squad car pulled up and a white officer accused Lucas of having stolen a woman's purse. It was the first time Lucas had any encounter with the police.

“I told him, 'No sir,' and that I was going to the store with $20 to buy groceries for my grandmother,” he said.

The officer said he was going to take Lucas to the woman and have him identified.

Lucas knew he hadn't done anything wrong. And knew he had to get the groceries home. So he told the officer that if the woman didn't identify him, he'd need the officer to run him back to the store and help him get the groceries to his grandmother.

Earnell Lucas at the location where he was shot in 1982 as a young Milwaukee police officer. (Photo: Angela Peterson/Milwaukee Journal Sentinel)

“In a moment, that officer just sped away and that was it,” Lucas said.

The incident left Lucas aware of the power a police officer has — and how important it is for officers to make the right decisions in the moment.

Lucas did not see that officer again until 1976 — a week after Lucas joined the force. He approached the officer and asked him: “Do you remember me?”

Lucas told him that incident had helped inspire him to apply to the academy.

Lucas would go on to serve 25 years with the Milwaukee Police Department, retiring as a captain on Jan. 21. 2002.

In the meantime, he got married — June 10, 1979 — and the couple had two children, Tyren, now 39, and Jonelle, 37. The couple divorced in 1984. Lucas remarried 10 years later. He and his wife, Linda Fitzgerald, will celebrate their 25th anniversary in April.

In all of his years on the force, he never fired his weapon.

On the day he was shot, he never had a chance.

* * *

Outside the apartment that day, Lucas' partner applied pressure to his face and got him back to the squad car.

Other officers responded to the call and confronted the man, ultimately shooting and killing Damron. A medical examiner’s report would later say he had been intoxicated.

In the ambulance, on the way to Mount Sinai Hospital, several things kept crossing Lucas' mind:

His children.

Trying to survive.

And the department.

Less than two weeks earlier, Dec. 23, 1981, officers John Machajewski and Charles Mehlberg were killed in the line of duty when they chased an armed robber into an alley. Machajewski died at the scene. Mehlberg died at Froedtert Hospital.

“When they were cutting off my uniform, I was thinking, 'Not again,' " Lucas said. "I remember going to their funerals and we were not over that.

"Well," he said, after a pause. "You never get over that."

The surgeon took out most of the pellets from Lucas’ face, but could not remove them all, including some near his right temple. To this day, if Lucas lays on anything harder than a pillow, he said it feels like he’s resting on a bed of rocks.

While hospitalized for five days, Lucas said there was a “wall of blue” of support as other officers, and even Chief Harold Breier, visited him.

The entire time in the hospital, Lucas said he felt that if he ever fell asleep, he would never wake up.

“I remember how swollen my head got and I remember when my dad came to my room and he saw me with all the bandages and broke down crying," Lucas said. "He told me something he doesn’t do as much of. He told me he loved me.”

Lucas said the only thing he could tell his father was to take care of his son and daughter.

Tyren was 2 and Jonelle was only 16 days old.

* * *

In the weeks after Lucas went home, the support from his job faded.

“My faith got me through,” he said.

There were times when a cop show would come on the TV and he would see the barrel of a gun on the screen and have a flashback of the gun being pointed at him.

The only person Lucas remembers calling him was an administrator for the city, whose job was to make sure that anyone who could work was working. Every week the man called: How are you feeling?

“I would tell him that I was feeling good and he would say, ‘Well, when are you coming back to work?’”

He rejoined the force four months later, in May of 1982, and went back to the same district and the same squad. The same streets, same routine.

There was no counseling, no discussion of trauma.

“I don’t even know if we knew what that meant at the time,” he said. “But knowing what I know now, I realize that I was traumatized from the shooting.”

* * *

As of Dec. 21, there had been 101 homicides in Milwaukee this year: 83 percent of the victims were shot, 75 percent were black; 73 percent were between the ages of 18 and 39, and 78 percent of the victims were men, a Milwaukee Journal Sentinel analysisfound.

Though homicides are down from 139 in 2016 and 118 in 2017, the city's homicide rate this year is running at about 11.6 per 100,000 people, which was on pace with Chicago, a city that has drawn national headlines for gun violence.

Lucas and others say each incident visits more trauma on the city — especially its youngest residents, many of whom live in neighborhoods surrounded by poverty and violence. Sometimes the young people witness it, sometimes they are victimized by it, and sometimes they perpetrate it.

“It’s one thing to be shot at in Vietnam, Iraq or Afghanistan, but it’s another thing to be shot at near your school and in your own neighborhood,” said Ramel Smith, a psychologist who grew up in the city's distressed 53206 ZIP code.

While soldiers eventually leave a war zone, for many urban youth, the trauma occurs at home.

“Our young people are dealing with poverty, violence and crime every day in parts of our community and that can cause mental illness,” said Brenda Wesley, a long time mental health advocate in Milwaukee. “But the stigma associated with a mental illness is so high that people are scared to ask for help or seek it out in the first place.”

Wesley said African-American boys are often told to “suck it up” when it comes to something tragic, or to “be strong” and not show any emotions. If they do, they may come across as weak.

“Most of the kids we see misbehaving are crying out for help,” she said. “We have to recognize that and get them connected to the right resources.”

Smith agreed.

Sharon Bea (left) talks with Sheriff-elect Earnell Lucas before the start of the Milwaukee County Sheriff's Deputy retirees luncheon in Hales Corner (Photo: Angela Peterson/Milwaukee Journal Sentinel)

“How can we expect them to concentrate in school when they have been exposed to everything from seeing their mothers abused, fathers incarcerated and the untold violence that they see and are told not to talk about it?”

* * *

On June 23, 2018, Lucas visited the "We Got This" summer garden program on the corner of North 9th and West Ring street.The program is aimed at African-American boys, ages 12 to 17.

They arrive each Saturday to work in the garden, pick up trash in the neighborhood and meet with mentors. At the end of the four hours, they collect a $20 bill for their efforts.

Lucas stopped by to support the founder of the program, Andre Lee Ellis.

He listened intently during a small group session, as 10 boys described what they have witnessed: Relatives shot. Neighbors beaten. Squad cars tracing the streets.

One boy, 12, described how his cousin was killed in front of his house, and how he and his mother hid in a basement closet while armed men stormed inside, searching for anyone who may have seen what happened.

"I thought I was going to die,” the boy said.

“We could hear them in the house and my mom kept telling me to be quiet. We hid and didn’t come out until they left.”

The incident happened two years ago. No one has been arrested in the case.

The boy said he never saw the shooter’s face, but he remembers seeing his cousin lying in a pool of blood on the sidewalk.

“We don’t talk about it, but whenever I hear a loud noise, I think about it,” he said. “We moved after that happened, but I still remember it.”

Lucas stepped forward and told the boys his own story.

“I was shot and let me tell you right now, it stays with you forever,” he said. “It can get better over time, but when you face something like that it’s never easy.”

He told them he was not able to begin healing until he started talking about what happened.

“I want you to know if any of you want to talk to me about anything, give me a call and we can talk it out," he said. "You can’t keep that in.”

He gave his phone number to Ellisto share with boys who needed it.

* * *

The visit with the boys stayed with Lucas.

In an interview weeks later, he talked about how the Milwaukee Police Department — like other law-enforcement agencies — had gotten better at addressing trauma.

He noted the death of Officer Charles Irvine Jr., 23, who was killed in June after the squad car in which he was a passenger crashed on the city’s northwest side. Irvine was the first Milwaukee officer killed in the line of duty in 22 years.

Less than two months later, Officer Michael J. Michalski, 52, a 17-year veteran, was shot and killed while trying to arrest a suspect.

Every officer who requested or needed to talk with someone was given support.

"That's as it should be," Lucas said. "We just need to provide the same kind of care for our most vulnerable children.”

* * *

In August, Lucas won the Democratic primary for sheriff, defeating Acting Sheriff Richard Schmidt by a 57 percent to 34 percent margin. In Milwaukee County, a Democratic stronghold, that made him a shoo-in for the job.

But at a time when he should have been looking forward, he found himself pulled back.

It was Aug. 24, Lucas was attending a law enforcement appreciation night at Miller Park when, as he was walking to the parking lot, he was tapped on the shoulder.

He turned. It was a young man he had never seen before.

"Are you Earnell Lucas?"

"Yes."

The young man said his father was John Machajewski, one of the officers killed Dec. 23, 1982.

Lucas froze.

“He said, 'I didn’t mean to hit you with that,' ” Lucas said, recalling the incident. “I worked with John in the same district. I knew him well. I knew his wife, but never met this young man."

It was a reminder that, no matter how many days have passed, the day Lucas was shot will always remain close.

“Sometimes you may forget about it and then something happens," he said. "Something will always take you back to that moment.”

[This story was originally published by Journal Sentinel.]