A ‘silver lining:’ Promotores de Salud fill gaps in public health response through community trust

This story is part of a larger story led by Dana Ullman, a 2021 California Fellow who is reporting on disparities in the quality and access to health care for Latino and Indigenous peoples in Mendocino County.

Her other stories include:

In Covelo, COVID clinics expand to reach more communities across Mendo

Share your pregnancy story: have you recently had a baby or support someone who has?

What’s in a harm reduction kit, anyway?

Our resource guide for harm reduction and drug treatment services in Mendocino County

Looking for light in the darkness: Addressing suicide in Mendocino County

For birthing parents on the Mendocino Coast, labor and delivery centers are a disappearing act

Dana Ullman / The Mendocino Voice

WILLITS, 7/18/21 — In spite of fifteen months of pandemic living in their three-room mobile home, Jerry and Alma Gutiérrez, their six children, three birds and house cat Ninja, remain a healthy and cheerful family. When a shelter-in-place order was issued in March 2020, the Gutiérrez family resolved to stay tight-knit despite the tight quarters. Jerry continued to work while the children — ranging in age from 6 – 17 — stayed home with Alma, who attended classes remotely.

“It’s been very hard,” says Alma. “Especially with remote learning, I had to have one [child] in one room, one in another room, one at the table.”

“Sometimes the internet went bad and we didn’t know what to do,” says Juan, 9.

Jerry, who has a heart condition and Alma, a diabetic, have had to be extra careful. Amidst the chaos of remote learning, an unstable internet connection, Jerry’s work schedule and the understandable hesitation at the risk of exposing their family to COVID-19, both parents found it difficult to obtain basic information and necessities like food.

Graciela Botello, a promotora, became a lifeline to the family. Botello is one of seven Promotores de Salud (health promoters), specially trained community health workers. Though formally the first of its kind in Mendocino County, the model is quite common throughout Latin America but has gained traction in the US during the pandemic. Throughout the pandemic, Promotores de Salud have been critical to local public health responses for Latino communities across the United States. The pilot program was recently extended for another year in partnership with Nuestra Alianza de Willits and Mendocino County.

Botello, known to many as ‘Chela,’ has an almost familial relationship with the Gutiérrez family, since their oldest son, now 17, was enrolled in the Head Start program 15 years ago, where she has worked for 20 years. Botello checked in with the family weekly, hand delivering food, clothing, and helped them navigate the system of testing and vaccines, when they became available.

“We were lucky we didn’t get sick and she was always checking in,” says Jerry. “There wasn’t a lot of [public health] information in Spanish, and Alma, sometimes she understands some things better in Spanish. Some things are written in English and it doesn’t make sense to her, she couldn’t understand. Chela would help her with that and make sure she understood what everything meant. She called me with vaccine information when there was a vaccine clinic after work in Laytonville. I wouldn’t have known otherwise.”

Jerry, who works full-time, often missed the vaccine clinics.

“She walked us [through] step-by-step,” Jerry says. “The first time, we couldn’t make it because I was working and she kept making phone calls to see what time [the clinic] was there. One day she called: ‘I know you’re getting off late but go and get the vaccine. Go, go, go! They’re gonna wait.’ So, we rushed over, waited in line, and were able to get the vaccine.”

![The Gutiérrez family: Jerry and Alma with their children from left, Gloria, 13, Juan, 9, Julian, 8, Gabe, 7, and Diego, 6. Jerry, 17, not pictured. With four children under 12, not yet old enough to receive the vaccine, the family continues to take every precaution while also enjoying family time. “We’ll probably have a party [to celebrate when] Covid’s over.” says Juan. Dana Ullman / The Mendocino Voice](/sites/default/files/styles/inline_image/public/u106571/Screen%20Shot%202021-07-20%20at%201.40.15%20PM.png?itok=n14SkWqt)

Trained for their positions, but not necessarily licensed healthcare providers, the promotores already have the trust of their communities, filling gaps in public health information through translation, providing COVID-19 testing, referrals for vaccinations, and responding to the direct needs of their community with cultural understanding. In Willits the promotores provide tailored support including food and clothing, outdoor group exercise, and support for families who have lost a loved one to COVID-19.

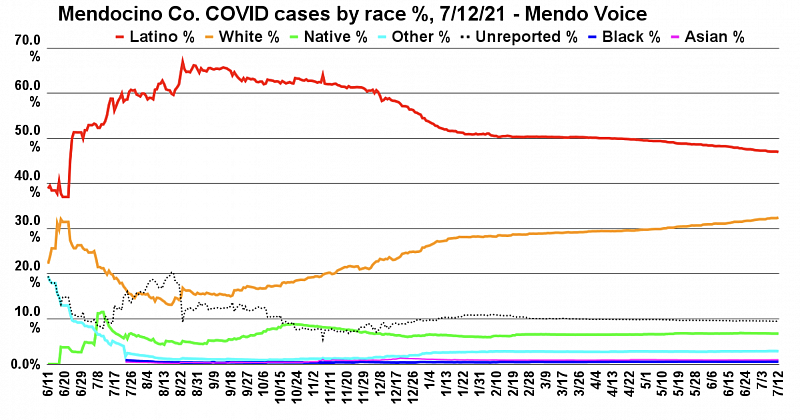

Latinos make up 39.4% of California’s population, yet represent 56% of COVID-19 cases and 46.4% of deaths from the virus (update), according to the state’s COVID-19 dashboard. In Mendocino County, COVID-19 has had a disproportionate impact on the Latino Community – 48.8% of all COVID-19 cases to date have been recorded in the Latino community, who make up only 27.18% of the county’s population.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Hispanic or Latino persons are two times more likely to contract COVID-19, almost three times (2.8) more likely to be hospitalized, and 2.3 times more likely to die from COVID-19 when compared to white, non-Hispanic persons. Due to public health disparities such as reduced access to preventative high-quality healthcare, high rates of comorbidities such as obesity and diabetes, the COVID-19 pandemic has had an acute impact on Latino communities throughout the United States.

Essential workers, the promotores have stayed committed to their communities in Ukiah, Laytonville and Willits throughout the pandemic, even when they were slowed down by multiple COVID-19 exposure scares and losing family members to the virus.

“Personally, it has been a tough year,” says Botello, who has lost two family members to the pandemic, and spoke through an interpreter. “Many people may not understand it, but when they come from another country and do not have the ability to communicate…[I] know things and see the needs that one has. I think that is what has always motivated me to want to help people. [Community] is what motivates me the most. I believe that through Promotores we can bring the information, we can also inform them of what services there are in the county, because many people do not know.”

On a warm day in late June, promotores Diana Gomez Martinez, Ana Almanza, and Jaime del Aguila, packed boxes of potatoes, canned goods, sweet cakes and stuffed frozen chicken into a cooler.

Ana and Diana, along with Diana’s daughter, traveled to a remote vineyard in Potter Valley where between eight and ten farm workers live and work. A plastic table was set-up and stacked with boxes of food. One worker came out, shyly at first, and then another and another.

Each promotor has personal experience and a unique understanding of what their community’s needs are. Their work is built on confianza (confidence) and existing relationships in their own community that go beyond testing portals and public health efforts and directly engage with the day-to-day needs of a family like the Gutiérrez’s. Diana worked in vineyards and pear orchards for over a decade after she moved to Mendocino County from Michoacán, Mexico. When the pandemic hit, she knew exactly where she needed to go.

“When I worked in the fields there were times when I had nothing else to eat but soup and if I ran out of that I would not eat for two days,” Gomez Martinez says through an interpreter. “We have been carrying [food] pantries lately [and] giving diapers to those who have small children… because in the field I know that women leave their babies as young as forty days [while] they go around working in the fields.”

Diana is “energized” being able to help people who don’t have knowledge of what resources the community has to offer, specifically monolingual Spanish speakers.

“I understand a little bit,” says Gomez Martinez, who is enrolled in ESL classes. “I can defend myself. I can find things, but there are people in this community who don’t, and so I’m doing it for people like them.”

The Latino community speaks out

Last spring, case rates surged in the Latino community, reaching 66.9%. In response, local Latino leaders, advocacy groups and Spanish-speaking media outlets grew concerned at the lack of Spanish language translation of critical public health information.

“Our concern is that Spanish communication has been an afterthought,” said Roseanne Ibarra, of Mendocino Latinx Alliance, in a virtual meeting between Latino leaders, the Mendocino Department of Public Health and the Board of Supervisors in June 2020.

A series of public presentations spearheaded by Latino community leaders ensued. On June 10, 2020, Mendocino Public Health began including ethnicity on their daily case update, but it wasn’t until after these presentations on July 2 that Public Health began releasing daily case updates in Spanish on Facebook. Subsequent to these community-led meetings, the county published bilingual PSAs more consistently and a COVID Equity Workgroup began meeting regularly.

Laura Diamondstone, an epidemiologist and artist who lives in Anderson Valley, saw red flags early on as she watched essential workers sharing transportation to and from work, frequently without proper PPE. She had an antidote.

“The community health worker model in general is an effective response to addressing inequities to respond to both critical emergencies and health disparities,” Diamondstone wrote in a statement. “People who are disproportionately affected by health inequities have valuable insight on how to reach the most marginalized within their communities.”

For six months, with a proposal in hand for a Promotores de Salud model, she went door-to-door looking for an organization to call home, and fiscal support. Finally, she landed on Nuestra Alianza de Willits (NAW), where volunteers were already responding to immediate needs during the pandemic, sewing thousands of masks and becoming a food bank.

“We saw need and went for it,” says Dina Hutton, who is an ESL teacher and NAW’s board president. Grassroots from the beginning, NAW started on a blackboard when Hutton’s ESL students discussed what they wished they had in the community. Hutton wrote down their wishes: an after school program, a summer program for their children, among other things.

“That was our strategic plan. I told them no one is going to do this for you. Do you want to do it yourselves?”

Lucy Tafoya (left), a promotora, hands out water and talks with fellow promotoras Diana Gomez Martinez, Chela Botello and a participant at the ‘10,000 Steps’ event in Willits on June 26 2021. Dana Ullman / The Mendocino Voice

“It’s the only model I think would work,” says Hutton. “Especially in the situation of a poor family that’s not documented. That’s when the promotores can be so helpful. Their community is here and just as important as anyone else.”

In November 2020, the pilot was launched with fiscal support from Mendocino County. The results have “exceeded expectations.”

“They keep referring to it as a pilot, but it’s already proven itself as an essential component of any public health effort,” says Diamondstone. “Whether it be just simple health promotion to chronic disease management to infectious disease epidemic response, I see Promotores de Salud as being fundamental [to Mendocino County Public Health].”

Diamondstone stepped away from the program believing “in using privilege to open doors, get people to the table then give them the seats — essentially get out of the way and give credit where credit is due.” To effectively address the long-term impact and health disparities the pandemic has spotlighted, she says we need more input from these communities.

The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbates long-standing public health inequities

It’s a misnomer to call the COVID-19 virus “a great equalizer,” most notably coined by Governor Andrew Cuomo of New York, among others, when social determinants such as comorbidities, class and race are taken into account. The pandemic has spotlighted long standing disparities in healthcare and access to healthcare globally.

In a presentation coordinated by the Mendocino Latinx Alliance and the Community Foundation of Mendocino County, Health Disparities: The Latinx Experience During COVID-19, Dr. Aguilar-Gaxiola, director of the UC Davis Center for Reducing Health Disparities, emphasized the need to “re-frame the pandemic as a “community problem” not a siloed “public health” problem” to address the long-term impact of the pandemic. One key to this reframing are trusted sources of information that have the power to change behavior.

Even as vaccines were made more readily available, Latino vaccinations lagged making up only 16.1% of all cases in April but as of July 13, 52.3% are partially vaccinated thanks in part to the work of promotores. Through social media, phone trees and even going door-to-door, the promotores signed-up more than 500 people for testing and vaccinations since November.

Recently they have started testing, too. In some cases, barriers to accessing quality healthcare for Latinos can be complex, particularly for undocumented immigrants, who may be monolingual speakers, essential workers or have fear of interacting with law enforcement or county officials.

Once vaccines became available to farm workers, Diana started texting her contacts, “We have them available, it’s really important for you to get vaccinated.” Diana said that sometimes they would say, “‘Yes, sure, we’re going to do it,’ and then they wouldn’t.”

“The other part too is they work six, seven days a week sometimes and it was difficult for them,” adds Keily Becerra, program coordinator for Promtores de Salud.“Some of them did mention, ‘If it’s on a Sunday at a convenient time, we would be able to do it. Otherwise we can’t, because we’re working in the field all day.’”

Nationally the word “hesitant” has been used to describe the unvaccinated but a poll from the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) published in May found that for Latinos the problem appears to be more about lack of or mis-information than hesitancy.

The KFF report found that Latinos were about twice as likely to want to receive a vaccine as soon as possible than white or Black people polled. Not one farm worker Diana and Ana met in Potter Valley, for example, had received any information about vaccines beyond Facebook until meeting promotoras. Though there was hesitation in the moment — “Sin prisa,” said one man. “Tienes que esperar y ver,” (“No rush. You have to wait and see.”) — they hadn’t been offered the opportunity and couldn’t easily take the time off working in rotating shifts and sharing a vehicle. Promotores de Salud recommend pop-up vaccination clinics at work sites.

County Public Health Officials Respond

Prior to becoming a promotora, Becerra was frustrated by the lack of response early on from officials.

“We knew this was going to happen,” Becerra told the Board of Supervisors in June of last year. “We could have prevented so much…the lack of outreach to the Latino community, the lack of communication and accurate information should not be a reason for so many people in our community to become infected with this disease.”

The promotores say they have been encouraged by the reception from county officials.

“One of the silver linings in our county is that the pandemic has revealed to us gaps in our capacities and our capabilities,” County Deputy Health Officer Dr. Noemi Doohan told The Mendocino Voice at a virtual COVID-19 update. “For example…our bilingual, multilingual services have not been sufficient and we’ve worked hard through this pandemic to improve them.”

The question remains: how can equitable responses to the pandemic be integrated into the existing public health structure moving forward?

Behind the scenes, Becerra is working on a long-game plan for the program, which is formally the first of its kind in the county. The promotores have discussed how to prepare for other emergency responses such as wildfires, support for those struggling with the long-term impacts of the pandemic including mental health, and expansion of the program to other parts of the county.

“We would love to see this program adapted countywide,” Becerra says. “The Willits community is not the only community affected by all these issues. We can see the potential benefits of having a promotores program throughout the county.”

From the intersection of community health and racial justice, the pandemic has only strengthened Becerra’s resolve and commitment to the work at hand and find a way to blend grassroots organizing into existing healthcare structures. “I think it’s about finding… a happy medium where ordinary people run a grassroots program and have the backing of the health professionals. Having that kind of infrastructure that we see at health centers…finding a balance between those would be great.”

“With Promotores,” Becerra continues, “we want to make sure that we’re also employing the right people. [Promotores] don’t necessarily have the formal education or resumé to get them a job with the county, but they know the community and know how to do the work. That’s actually more strategically successful for us. Once you move into one of these other places where the rules are a little bit more rigid, it changes the heart of the program a little bit. That’s a challenge that comes to mind when we think about moving forward.”

Another long-term development Becerra would like to see, echoed by other promotores, would be more Latinos in county positions that are culturally sensitive and can relate to the experiences of the Latino community, especially monolingual Spanish speakers. For now, the Promotores de Salud will continue to meet the needs of their community pandemic and post-pandemic.

“It showed us how successful something like this could be and also what improvements we can make. We’ve just learned so much also about our own community through this program,” says Botello, reflecting on the past year.

Diana was studying to be a nurse before moving to the United States. When asked if she would go back to nursing school, Diana shakes her head and gives a cherubic smile. “I’m happy doing this work.”

Dana Ullman reports on health-related stories with support from the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism: https://centerforhealthjournalism.org/ This article was produced as a project for the 2021 Center for Health Journalism California Fellowship. Feel free to reach out to her with your health-related questions, tips and comments: dana@mendovoice.com

Adrian Fernandez Baumann contributed to this story.

[This article was originally published by The Mendocino Voice.]