Tribune investigation: What it’s like for SLO County renters stuck in bad housing

This story is part of a larger project, "Standard of Living," by Lindsey Holden, a participant in the 2019 Data Fellowship. The project focuses on the experiences of low-income renters living in poorly maintained housing in San Luis Obispo County.

Other stories in this series include:

Q&A on renter’s rights: What you need to know as a tenant in SLO County

Paso Robles couple says landlord covered up unhealthy mold problem. So they sued

We surveyed nearly 200 SLO County renters on their housing conditions. Here’s what they said

Tribune investigation: Erratic code enforcement leaves SLO County renters vulnerable to abuse

Tribune investigation: Inspections protect renters from slumlords. Why did SLO’s program die?

Blanca, an Oceano renter, has struggled to get her landlord to make repairs in her apartment during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Laura Dickinson LDICKINSON@THETRIBUNENEWS.COM

Editor’s note: This is the first story in The Tribune’s monthlong “Substandard of Living” series examining the experiences of low-income renters living in poorly maintained housing in San Luis Obispo County. The Tribune spent nine months investigating the issue by talking to residents, conducting surveys, speaking to experts and evaluating government resources.

To read this story in Spanish, click here » La investigación de Tribune: Cómo es para inquilinos del condado de SLO atrapados en malas viviendas.

**

All Blanca wants is a safe, clean home where she can raise her children and visit with friends. But no matter how much she scrubs her Oceano apartment, it never looks as it should.

The rental has old, dirty carpet that’s peeling away from the floor, cabinets and drawers that are stained and falling apart and broken windows in the living room and one of the bedrooms.

Blanca worked at a Pismo Beach hotel until she was laid off due to the coronavirus outbreak. She now spends most days in her apartment, caring for her disabled husband and two of her sons. On a recent visit, one of her sons sat on the couch doing his schoolwork on a laptop, his feet resting on a rug Blanca bought to cover the stained carpet.

Blanca has told her landlord about the problems in her apartment, but she’s struggled to get them fixed, especially after COVID-19 hit. She’s tried to move into a different unit in the same complex, but has repeatedly been told she doesn’t qualify, even though she’s never been given the opportunity to apply.

Blanca’s Oceano living room carpet is old, dirty and fraying at the edges. She bought a rug to cover the carpet, which is peeling away from the floor underneath. Laura Dickinson LDICKINSON@THETRIBUNENEWS.COM

The conditions of Blanca’s apartment take a psychological toll. She’s sad her house is never as clean as she wants it to be, she’s frustrated her landlord won’t let her switch apartments, and she’s too ashamed of her living situation to have guests over.

“I just want help to look for a new place that is comfortable, secure and clean for my kids,” Blanca told The Tribune in Spanish. “Because sometimes I feel like it’s my fault that I can’t provide them with a clean place to live.”

Blanca is one of many San Luis Obispo County tenants trapped in dilapidated housing because the system that’s meant to enforce state habitability codes does not hold landlords accountable for renting units that are unhealthy for residents.

To better understand the problem, The Tribune spent nine months investigating the issue by conducting hundreds of surveys, speaking with residents about their living conditions, consulting with housing experts and evaluating government resources. The Tribune is not using the full names of tenants who described their rental housing experiences to protect their privacy and prevent landlord retaliation.

Among the findings: Low-income residents face challenges across the county, but the difficulties are most severe for people of color, undocumented immigrants and residents who primarily speak a language other than English, as they also sometimes face discrimination when searching for new housing.

The cabinet door in Blanca’s Oceano bathroom is coming apart at the top, making it difficult to open. Laura Dickinson LDICKINSON@THETRIBUNENEWS.COM

Those at-risk residents often have few places to go for help because little government oversight of rental housing allows landlords to get away with renting old units that are falling apart.

In one case, tenants took legal action against the owners of Grand View Apartments in Paso Robles after living in poor housing conditions for years. But the owners opted to shut the complex down rather than fix millions of dollars in problems — leaving hundreds scrambling for a place to live when it closed.

Such situations promote a culture of fear among tenants, who frequently aren’t aware of their rights and are vulnerable to abuse.

“What happens is a lot of families put up with serious health and safety issues in their building because they’re afraid to report it to their landlord, because they’re afraid they could lose their home,” said Lucas Zucker, policy and communications director for the Central Coast Alliance United for a Sustainable Economy (CAUSE), a nonprofit that works with tenants in Santa Barbara and Ventura counties.

“Their landlord may find a way to evict them or may say, ‘Sure, I’ll fix that up, but I’m going to dramatically raise your rent in order to do so.’ And among people who are already living with a lot of fear due to their immigration status, they’re even less likely to report those things.”

Blanca, an Oceano renter, has struggled to get her landlord to make repairs in her apartment during the COVID-19 pandemic. She’s also been told she doesn’t qualify to switch apartments, even though she hasn’t been given the opportunity to apply. Laura Dickinson LDICKINSON@THETRIBUNENEWS.COM

BREAKING DOWN THE INVESTIGATION

The problem of substandard housing in San Luis Obispo County begins with the area’s high cost of living.

Ranked as the 10th least affordable place to buy a house with a median home price of $659,000, San Luis Obispo County is home to a large proportion of renters.

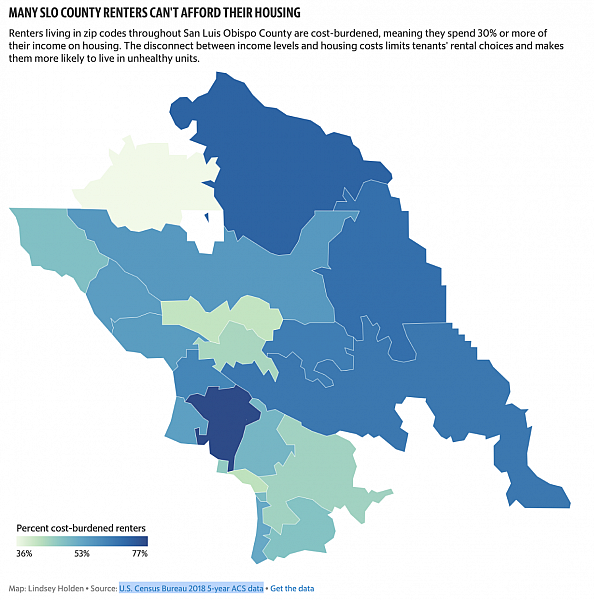

In fact, nearly four out of every 10 county residents are tenants living on someone else’s property, according to U.S. Census Bureau data. More than half of those residents are cost-burdened, meaning they spend 30% or more of their income on housing.

Meanwhile, many of those renters work low-paying jobs in the county’s two top industries: tourism and agriculture. They live paycheck-to-paycheck, and they often take whatever housing they can find — a dynamic that makes their housing situation even more precarious.

For many, rental options are slim, and complaining about poor conditions to their landlords or to code enforcement may leave them with no home at all.

To fully explore the issue, The Tribune embarked on an effort to reach those tenants and hear their stories. The Tribune modeled an effort used by CAUSE staff and volunteers in 2019, when they surveyed nearly 600 renters to assess rental housing conditions in Oxnard, Ventura, Santa Paula, Santa Barbara and Santa Maria.

Together with the Promotores Collaborative of San Luis Obispo County, part of The Center for Family Strengthening, The Tribune surveyed nearly 200 tenants — many of whom primarily speak Spanish — from San Miguel to Oceano, both in-person and online.

The project showed large numbers of low-wage workers live in poor apartments and homes for many years. Tenants raise their children and live out their retirements in rental housing with broken windows, dirty carpets, moldy walls and faulty plumbing because finding a new place to live is so challenging and reporting problems doesn’t always get results.

Some renters told The Tribune and the Promotores they avoid reporting problems to their landlords because they fear having their rent raised or being evicted from their homes. And other tenants said they’ve reported maintenance problems only to see their landlords turn a blind eye or tell them they must pay to fix the problems themselves.

Undocumented immigrants who lack the Social Security numbers needed to apply for rental housing are even more vulnerable to landlord abuse — especially those who primarily speak languages indigenous to regions of Mexico, such as Mixtec.

The simple fact is, tenants living with poor conditions have few options.

SURVEY RESULTS: WHO WE TALKED TO AND WHY

The Tribune and the Promotores conducted in-person surveying primarily in working-class areas where most tenants speak Spanish, including neighborhoods in San Miguel, Paso Robles, Oceano and Grover Beach. Nearly two-thirds of renters surveyed identify as Hispanic or Latino.

The Tribune opted to focus on these areas because such renters are the most vulnerable to landlord abuse due to language barriers, discrimination, immigration status and income levels.

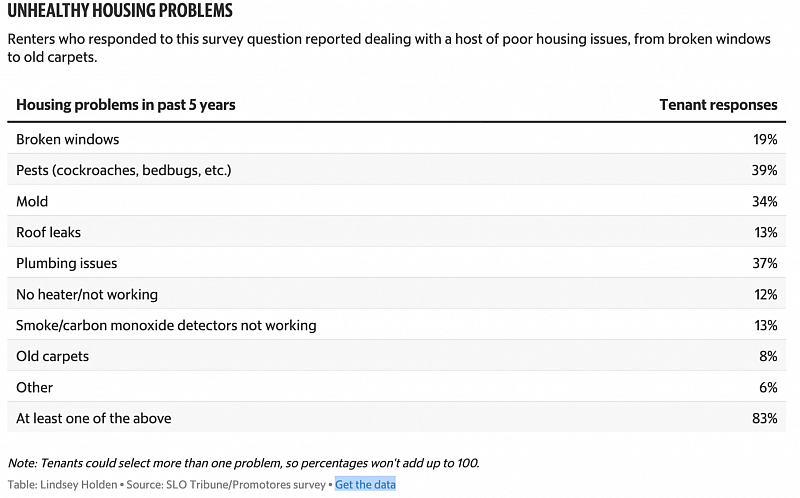

More than eight in 10 surveyed renters reported they’ve experienced at least one substandard condition in their rental unit during the past five years, including broken windows or doors, pests, mold, roof leaks and plumbing problems.

The Tribune and the Promotores also asked renters how they deal with problems in their rental housing units. Tenants could select more than one response — they’ve fixed problems themselves, lived with them, gotten help or received no help from landlords or asked the city or county for help.

Almost 40% of renters who answered the question said they repaired things themselves, continued to live with problems or sometimes didn’t get things fixed.

UNHEALTHY HOUSING PROBLEMS

Renters who responded to this survey question reported dealing with a host of poor housing issues, from broken windows to old carpets.

Nearly 60% of renters said their landlords eventually fixed issues for them. But 20% of the tenants who said their landlords made repairs also reported making their own fixes, putting up with problems, having their rent raised after things were fixed or waiting a long time for repairs.

Only 4% of those who answered the question — 6 people — said they took the step of contacting their local governments for help.

Most of the tenants surveyed lived in large or small apartment complexes, indicating poor rental housing conditions are a problem for all types of renters — not just for those living in homes owned and managed by individual landlords.

More than half had lived in their rental unit for more than five years, and a few renters said they had lived in their homes or apartments for decades.

Among the tenants surveyed, renters of color were more likely to live in crowded housing.

Nearly a third of respondents said five or more people lived in their rental unit, most of whom were tenants of color. Only two white tenants reported living in a rental with five or more people — the remaining tenants identified as Hispanic or Latino, Black or Mixteco.

DEALING WITH POOR HOUSING A STRUGGLE

Even if renters are able to get poor conditions in their units fixed, the experience can be stressful and frustrating.

Miranda has had panic attacks only twice in her life — once when her father died and once when she was unable to bring her baby boy home from the hospital because the walls of her Cambria home were infested with fungus.

“It was stressful for a normal person,” she said. “And then going postpartum, it was 10 times more stressful.”

While Miranda’s son — who was born prematurely — was still in the NICU, she and her husband started noticing there were mushroom-like growths sprouting up around the windows of their rental home. They looked moldy and felt wet and squishy.

The couple had experienced previous issues with roof leaks and the water heater, and Miranda thinks the house’s age may have contributed to the problems.

“The people who lived there before, they really didn’t complain about anything — they didn’t really care for the house,” she said. “I don’t think (the landlords) were used to tenants who would speak up and say something.”

Even before Miranda and her husband discovered fungus in their wall, their landlords had told the couple they could be on the hook if additional repairs were needed.

“They started telling us if more stuff happened, they would raise the rent or make us pay for stuff,” Miranda said.

Miranda’s landlords had to tear out the wall to remove the fungus and didn’t charge the family rent while the repairs were being made. But Miranda couldn’t settle her baby in at home once he was released from the hospital. She had to take him to a relative’s house, instead.

Just after Miranda gave birth to her son, she and her husband began noticing fungus growing on one of the walls in their Cambria rental home. Mold was visible on the wall, and they spotted fungus around window sills. Courtesy photo

And that’s not the only poor experience Miranda had with rental housing. She had to take a previous landlord to small claims court to get her deposit back.

This occurred after a toilet began leaking into the couple’s bedroom, and they had to sleep in the garage for a month.

According to San Luis Obispo County Superior Court records, a judge awarded Miranda and her husband a portion of the money they requested.

“There are people who would’ve been, ‘Oh, I’m sorry, keep my deposit,’” Miranda said. “Not me. I’m not a complacent person.”

After Miranda’s son was born, she and her husband began looking for rentals in the Five Cities area. Her family lives in the South County, and she wants her son to grow up there.

But it took the family almost 10 months to find a new place to live. Miranda, who is bilingual and identifies as a Latina, said she would talk to landlords and property management companies on the phone and noticed they would treat her differently once they saw her in person.

She and her husband both have jobs, and they maintained a good relationship with their previous landlord — even after the incident with the fungus.

Even so, she said, landlords would choose a different tenant or assume she and her husband planned to double up with another family.

Eventually, Miranda was able to find a rental in Oceano. But she was “shocked ... shocked” by how challenging the process was.

TENANTS STRUGGLE TO EXERCISE THEIR RIGHTS

Tenants dealing with poor rental housing face an uphill battle if they decide to exercise their rights as renters, two housing attorneys who work with renters told The Tribune.

They said it’s tough for tenants living with substandard conditions to persuade their landlords that they’re breaking the law — and there are few legal resources available to help residents.

Frank Kopcinski and Vincent Escoto of California Rural Legal Assistance (CRLA) assist tenants dealing with evictions and habitability issues.

They said the combination of a low rental housing vacancy rate and a transitory student population makes it easy for landlords to find new renters, sometimes in spite of poor conditions.

Kopcinski, directing attorney, said they see such problems in all types of housing.

“I don’t think it’s one structure or the other,” he said. “It’s a problem that we see all up and down the county with different landlords.”

They also said tenants frequently aren’t aware of their rights, which makes them less empowered in their housing situations.

“I’m really surprised about the number of people who think the sheriff is going to come to their door,” Kopcinski said. “They’re not even aware of an eviction process.”