Trump stokes anxiety among U.S. citizen kids of undocumented parents

This article was produced as a project for the Dennis A. Hunt Fund for Health Journalism, a program of the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism. It's the first in a series of stories exploring how the Trump administration's immigration policies are affecting the physical, mental and emotional health of the kids of undocumented immigrants and health providers and educators who work with them.

Hampstead Hill Academy students in a hallway outside a classroom. Victoria Samo Jordan for USN&WR

Katie Vincent was in a hallway at Hampstead Hill Academy, a Baltimore public charter school, when she heard the piercing, anguished cries reverberating from a nearby classroom. This wasn’t one or two kids weeping or acting out. This was loud, hysterical, collective keening unlike anything she’d ever heard. Vincent, a teacher, ducked into the classroom and saw almost each of the 22 third-graders in the room wailing inconsolably.

Some kids draped their arms around classmates, trying to comfort them. A handful stared into space. The class’s teacher, Kelly Durkin, a drama instructor, looked like she was on the edge of breaking into tears. Vincent stepped back into the hallway and called for backup, summoning Steven Plunk, director of restorative practices, and Felicia German, director of Latino outreach. Plunk often convenes restorative circles, in which kids gather in a circle and talk about various issues, to build a sense of community. German speaks fluent Spanish and has built strong relationships with many of the school's Latino families, some of whom are primarily Spanish-speakers.

When the kids had filed into class at 11 a.m. on this day, January 19, following a brief recess, four students were already sobbing. Shortly, seemingly all the students were bawling. Gently, Durkin asked what was the matter. Through their tears, a handful of the kids explained: They were terrified that Donald Trump – who would be sworn in as president in a little more than 24 hours – would deport them or their parents. Apparently, someone had said something about Trump and deportations during recess, the idea spread and now the entire class was melting down. “I don’t want mommy and daddy to have to go away,” some children said, as Vincent recalls. Others lamented, “He [Trump] is going to make us go back to Mexico.”

Teacher Kelly Durkin near a classroom at Hampstead Hill Academy. Watching third-graders break down over President Trump's immigration enforcement approach was the "saddest" thing she'd ever seen.

Located in a neighborhood dominated by well-kept row houses, Hampstead Hill has a diverse student population; about two-thirds of the kids in this class were Latino. Some of their parents are from Mexico; others from Central America. Almost all of the Latino students are U.S. citizens, by virtue of having been born in the United States, but many have at least one parent who’s undocumented.

Teachers are accustomed to dealing with emotional displays from individual students. But not this.

“It was the most heartbreaking thing I’d ever seen,” Durkin says.

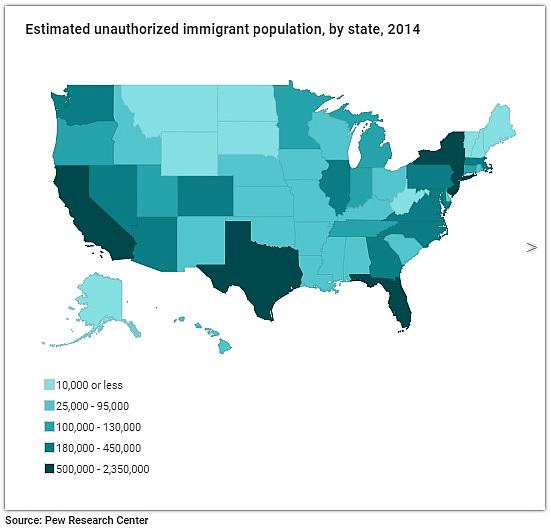

About 4.7 million U.S. citizen children have at least one parent who’s undocumented, according to 2014 estimates (the latest available) by the Pew Research Center. Another 725,000 children who are undocumented are believed to live in the U.S. Overall, there are an estimated 11 million undocumented people in the country. And nationwide, these kids and young adults are coping with the kind of anxiety experienced by Durkin's students. Many worry daily that U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents will tear apart their family by detaining and deporting one or both of their parents.

This fear is affecting the well-being of kids in myriad ways. In Los Angeles, a 15-year-old boy, a star student, says he sometimes loses his train of thought when talking to friends because he’s preoccupied ICE might arrest his undocumented mom. Another boy, age 9, races upstairs to spy out the window whenever someone knocks on his family’s front door; he wants to make sure ICE isn’t coming for his undocumented mom.

A Wide Array of Negative Health Effects

Anxiety, hypervigilance and stress could lead to a multitude of immediate and long-term health consequences, according to a raft of studies and experts. A study of 91 Latino U.S.-born children ages 6 to 12 who have at least one undocumented parent suggests that PTSD symptoms as reported by the parents "were significantly higher for children of detained and deported parents compared to citizen children whose parents were either permanent legal residents or undocumented without prior contact with immigration enforcement." The research was published in 2017 in Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice and Policy. Kids of undocumented parents have significantly higher risks of anxiety, depression, low self-worth and social withdrawal, a separate study of more than 2,500 children of undocumented Mexican mothers in Los Angeles suggested.

“Growing up in fear has all sorts of adverse psycho-social consequences,” says Marcelo Suárez-Orozco, the Wasserman dean of the graduate school of education and information studies at UCLA. He’s researched and written extensively about the stresses facing college migrant students and on the challenges facing so-called Dreamers, young people in the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program.

Research shows that fear can weaken the immune system, which in turn can make someone vulnerable to gastrointestinal problems such as irritable bowel syndrome and ulcers. It can also accelerate the aging process and hinder the formation of long-term memories. One study suggests some undocumented parents may be less likely to seek medical care for their kids as the risk of deportation rises. Living with anxiety can also distract students from their schoolwork, which in the long run may affect their ability to obtain a good job with health benefits, a circumstance that could further undermine their health.

“In the short term, these children are not able to function. They can go to school, but there’s no way they can focus on their studies, on having a typical childhood experience,” says Susana Rivera, program director of Serving Children and Adults in Need, Inc., a nonprofit in Laredo, Texas, that's part of the National Child Traumatic Stress Network. “The children don’t want to go to school – what if when they come back their parent is gone? They think that if they’d been there, they might have been able to protect them. That is a huge burden to put on a child. These children are constantly in fear and survival mode.”

Longstanding Fear of Immigration Authorities

Fear of immigration authorities, or “la migra,” isn't new among undocumented immigrants and their kids. However, the administration’s aggressive immigration enforcement policies are distressing some kids of undocumented people as never before.

Some immigrant's rights advocates derisively referred to former President Barack Obama as “Deporter in Chief.” During the first seven years of Obama’s presidency, federal authorities deported more than 2.5 million people by way of immigration orders, more than any other administration. But Obama’s immigration policies were designed to deport those who posed a public safety threat, says Wendy Feliz, communications director for the American Immigration Council, an immigrant advocacy group.

By contrast, Trump launched his campaign in June 2015 by attacking Mexican immigrants: “They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists. And some, I assume, are good people,” he declared. He’s pledged to build a wall along the U.S.-Mexico border.

Trump is taking a much broader and more aggressive approach to immigration enforcement than Obama and other past presidents. In January, he signed an executive order broadening the groups of people prioritized for deportation to include unauthorized immigrants not convicted, but believed to have committed crimes. That would include an estimated 6 million believed to have entered the U.S. without passing through an official border crossing, immigration experts have said. Millions more arrived in the U.S. with temporary visas, which they overstayed. "The administration, from day one, has stirred up fear in America and used it as a powerful and manipulative tool," Feliz says. "This has had an impact on everyone, particularly children."

Asked about the anxiety the administration’s deportation policy is creating among children of undocumented people, Danielle Bennett, an ICE spokeswoman, noted that most of the people ICE agents have arrested since January, when Trump took office, have criminal convictions. “ICE is a federal law enforcement agency responsible for enforcing the nation’s immigration laws as enacted by Congress,” she says. “ICE deportation officers are committed to enforcing the laws they have sworn to uphold, and carrying out final orders of removal professionally and in accordance with law.

"Since January, ICE arrests comprise over 70 percent convicted criminals. Of those arrested without criminal convictions, nearly 75 percent have been charged with a crime, are an immigration fugitive or are a repeat immigration violator," she says. "These results clearly reflect the continued prioritization of enforcement resources on aliens who pose a threat to national security, public safety and border security." While most ICE arrests have involved convicted criminals, the agency has tripled the number of arrests of people with no criminal convictions since Trump took office, according to government statistics.

Matt O’Brien, the director of research for the Federation for American Immigration Reform, which supports Trump’s immigration policies, says undocumented parents are responsible for whatever fear their kids feel. “There are certainly consequences if their parents came here illegally,” he says. “It’s the parents’ actions that are breaking up the family." O’Brien, a former ICE attorney, compared what he calls the laissez faire attitude toward undocumented immigrants to the enforcement-oriented stance taken against crimes like embezzlement or burglary. “You never hear anyone argue embezzlers or burglars shouldn’t get a lengthy prison term for their criminal acts,” he says. (The Southern Poverty Law Center labels FAIR a “hate group,” alleging some of its leaders have ties to white supremacist groups. Dan Stein, president of FAIR, strongly denies the allegation.)

High Anxiety, Long Odds

The odds of any family in which one or both parents are undocumented being torn apart by an ICE detention and deportation are long. ICE has 20,000 employees in 400 offices nationwide, while there are an estimated 11 million undocumented immigrants in the U.S. But the anxiety felt by kids of undocumented immigrants and their parents isn’t mediated by the cold logic of arithmetic.

“Ethnic media covers these kinds of stories much more closely than the mainstream press,” says Roberto Gonzales, education professor at Harvard University’s graduate school of education. He conducts research on the factors that promote or hamper the educational progress of immigrant and Latino students. About half of the undocumented immigrants in the U.S. are from Mexico, and another 16 percent are from Central and South America. “Whatever coverage is in the mainstream English-language media, it’s fivefold or ten times higher in the Spanish-language press,” he says. “Many people in the immigrant community feel as though they’re under siege."

Edgar is comforted by his undocumented mother outside their home in Los Angeles. (COURTESY OF ROBERT DOLAN, SJ)

Among those who feel besieged is Edgar, a 15-year-old Latino student at a prestigious private Los Angeles high school. (Edgar is a pseudonym. U.S. News is not identifying him by his real name to protect him and his undocumented mother.) Edgar won an academic scholarship to the school, where the tuition is more than $20,000 annually.

Before winning the scholarship, Edgar attended Dolores Mission School, which is located in a poor, heavily-Latino neighborhood near two large public housing complexes two miles east of the skyscrapers and pricey apartment lofts of downtown Los Angeles. Three gangs operate in the neighborhood, and half of the school’s parents earn $25,000 or less a year. The school is part of the Dolores Mission Church parish, where the Rev. Greg Boyle, a Jesuit priest, served as pastor from 1986 to 1992. Boyle authored the book “Tattoos on the Heart: The Power of Boundless Compassion,” which recounts his work at Dolores Mission with gang members, about 200 of whom he’s helped bury.

Star High School Student Worries ICE Will Deport His Mom

For Edgar, the academic scholarship could provide a path out of a world of poverty and the threat of gang violence, but since Trump’s election, he’s been preoccupied with the possibility his parents, both of whom are undocumented Mexican immigrants, could be deported. She works as a domestic; he works in a clothing manufacturing factory. Edgar is the oldest of their four kids. “As soon as Trump won, my mind was just everywhere,” Edgar says. “The idea of building a wall, I find that just ridiculous. But I know it can affect me, God forbid, my parents get deported, me and my siblings wouldn’t know who would take care of us. I probably wouldn’t have the motivation to go to school anymore.”

About 15 seconds into the interview, the teenager looks down at his sneakers, suddenly overcome with emotion. “My parents have really helped me, I’m grateful and thankful for them. Without them I wouldn’t be who I am,” he says through his tears. “Before the election I wasn’t really worried about this. Now, it’s an everyday thing to think about.” Since Trump’s election, he says he’s had conversations with friends in which he’s lost his train of thought because he was worried about his parents.

In addition to the anxiety the Trump administration’s policy is sparking in many kids of undocumented immigrants, there’s anecdotal evidence and some research suggesting fear of ICE is prompting some undocumented parents to forgo health care.

In the suburbs of Portland, Oregon, for example, the Virginia Garcia Memorial Health Center runs 17 community health clinics that serve 45,000 people annually. Virginia Garcia's patients speak dozens of languages. Many of the people the clinic serves are of modest means; 20 percent of the patients are uninsured, and 60 percent rely on federal or state health insurance. The number of people who didn’t show up for appointments with physicians at Virginia Garcia’s largest clinic in Cornelius, Oregon, spiked after Trump's election. In January 2016, the no-show rate for primary care at the Cornelius clinic was 9 percent; it shot up to 15 percent in January 2017, the month Trump was inaugurated. "The no-show rate was higher for the primary care teams that had patients with kids [as opposed to teams that primarily see older patients]," says Caitlin “Cata” Marshall, primary care clinic manager at Virginia Garcia. One team saw an increase in no-shows in January 2017 of 18 percent, more than double the rate of the previous year. Fear of ICE drove the increase in no-shows, staffers believe. "The patients of Virginia Garcia speak more than 62 languages," says Kasi Woidyla, public relations officer for Virginia Garcia. "Our Latino patients are the only ones being threatened with deportation on a daily basis." Roughly 55 percent of Virginia Garcia’s patients are Latino.

Baltimore Educators Scramble to Calm Terrified Kids

Fear of deportation extends to U.S. citizen kids of undocumented immigrants, as the episode in Durkin’s class in Baltimore shows. On the day of the incident, when she reached Durkin’s classroom, German, the director of Latino outreach, was taken aback by the students’ collective despair. She consciously kept her emotions in check because she had to try to help calm the kids, and tearing up herself wouldn’t help. German and Plunk, the director of restorative practices, decided the best way to help was to take some of the most openly emotional students away from the classroom. They took about a half-dozen kids to another room.

Plunk knew that some of the kids had older siblings or cousins in the school. "Would it help to talk to them?" Plunk asked. The kids said yes. Plunk arranged for three or four older siblings or cousins to be excused from their classes, and they came in and consoled the third-graders. Eventually the kids calmed down enough that German and Plunk got them to their next class.

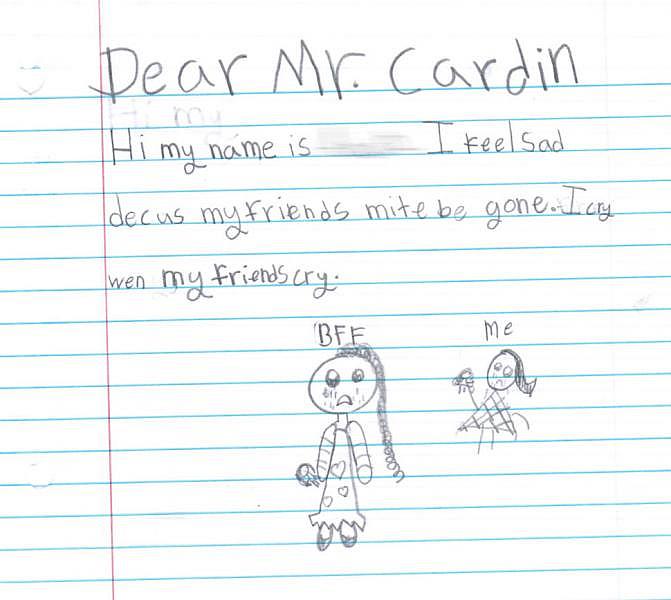

Meanwhile, Durkin asked the rest of her students to express their feelings on paper, with a drawing or a letter. She and her students talked about the power of writing letters to elected officials; some of the youngsters wrote letters to their senators, Ben Cardin and Chris Van Hollen, both Democrats from Maryland. "Dear Mr. Cardin," one student wrote, "I feel sad because I will miss my frindes and the USA. I do not want to go to Mesico." The student included a large frowning face. Some students kept breaking into tears. Others drew posters proclaiming “We want freedom!” and started chanting that, Durkin says. Some kids went around hugging friends and handing them tissues. One student, an American-born boy whose parents are U.S. citizens, wrote an angry letter to Trump laced with a couple of choice words. He has friends who have undocumented parents. “We began to write a letter as a class to Trump,” Durkin says. The students had her write, “We didn’t do anything to you.” Durkin didn’t send any of the letters because class ended before they could complete all of them.

A third-grader at Hampstead Hill Academy wrote to Maryland Senator Ben Cardin (D) to let him know she’s sad some of her friends might be deported. (COURTESY OF HAMPSTEAD HILL ACADEMY; DIGITALLY ALTERED TO PROTECT PRIVACY)

The episode awakened some Hampstead Hill educators to the depth of the anxiety some students with undocumented parents are coping with. “It was an incredibly emotionally taxing day [that] changed my perspective,” Vincent says. “Children, several of whom presented constant behavioral challenges in the classroom, were crying hysterically, and I saw a vulnerability in children that should never happen because of the actions of an adult.”

Hampstead Hill staffers learned they shouldn’t provide blanket reassurances to students. “I think none of us were prepared for this outpouring of emotion,” German says. “Some staff members said they were telling the kids not to worry and that nothing would happen. It’s a false promise; we don’t know for sure that nothing will happen. And in fact, later in the year, one of our parents was deported.”

Eight weeks after the episode, ICE agents arrested Jesus Peraza, an undocumented immigrant from Honduras whose son attends Hampstead Hill Academy. ICE detained Peraza near his home, shortly after he’d dropped off his fourth-grader son at school. ICE targeted Peraza because he’d previously been deported. Other than that, he’d committed no crimes. Members of the community lobbied ICE to allow Peraza to stay, but authorities deported him in June. The boy's mother continued to take care of him.

For the third-graders and other students who have an undocumented parent, the arrest and deportation of Peraza underscored the legitimacy of their fears, German says. “It’s not theoretical anymore,” she says. “It’s real.”

[This story was originally published by U.S. News.]

[Photos by Victoria Samo Jordan for USN&WR]