One North Carolina apartment complex was responsible for endless asthma attacks. Then the community started 'raising holy hell.'

Talis Shelbourne reported this project on the intersection of asthma, housing and health systems with the support of a grant from USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism's 2022 Impact Fund for Reporting on Health Equity and Health Systems.

Other stories include:

In 2017 Josie Williams and the Greensboro Housing Coalition walked through the Cottage Grove neighborhood, pointing out issues that can lead to health problems. Williams is now executive director of the group.

PHOTO COURTESY UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA-GREENSBORO

GREENSBORO, NC — Avalon Trace apartments used to represent one of Greensboro's worst asthma hazards. The 176-unit complex accounted for 20% of the asthma-related emergency room visits from the surrounding Cottage Grove neighborhood.

However, the complex’s identity as a health hazard, and its subsequent transformation, stands as a model for addressing health through housing.

The Greensboro Housing Coalition, a nonprofit umbrella organization, worked with health systems and a local university to pinpoint locations like Avalon Trace as asthma hotspots in the city.

In concert with residents and community leaders, the coalition then mounted a public pressure campaign against the complex’s owner and encouraged residents to report their poor housing conditions. Eventually, the owner sold to a new developer who brought the complex up to code, and even gave it a new name: Cottage Gardens.

Although the upgrades at Cottage Gardens are ongoing, emergency department visits have dropped significantly.

Cottage Gardens is the renamed apartment complex formerly known as Avalon Trace. A new owner purchased the complex in 2016 and is in the process of upgrading it. The Greensboro Housing Coalition, a partnership of governmental, nonprofit and community organizations, banded together to identify one of the worst asthma hotspots in the city, the former Avalon Trace apartments, and used a political and public pressure campaign that ultimately resulted in the apartment complex being sold, remediated and brought up to code. TALIS SHELBOURNE / MILWAUKEE JOURNAL SENTINEL

For Josie Williams, executive director of the Greensboro Housing Coalition, it all started with building trust in the community.

“We’re working with those who have the lived experience,” Williams said. “We don’t move until we have the decision-making of the residents.”

Poor housing, health normalized for residents

The median income in southeast Greensboro’s Cottage Grove neighborhood was a mere $12,500 in 2018, and 80% of residents were renters.

Dozens of those residents lived in Avalon Trace.

Although the building had 176 units, only 127 were habitable, as nearly 50 had been overrun with rats, raw sewage, cockroaches and mold.

Stephen Smoot, 69, was a native-born New Yorker who was new to the state when he moved to Avalon Trace in 2015.

After he started living there, he described the apartments as “trash.”

“The place was filthy,” he recalled. “There was carpet everywhere. Place smelled like pretty hell (because) the carpet holds every aroma you put into it. My bathroom had a sink hanging off the wall and all that held it up was a stick. There was black mold around the tub.”

He remembered taking a break from barbecuing one day when he noticed his bedroom window appeared noticeably darker. He went inside to check.

“I pulled those drapes, and the window was covered with flies on the inside,” he said. “There had to be hundreds of them.”

Smoot also began using a breathing machine. He said although he had smoked for several decades, he never had problems breathing until he moved into the apartment.

“If you’re lying here and breathing that (mold), even if you didn’t smoke, you’d probably still need that pump,” he said.

Smoot chose not to move because he had trouble finding a place once he came to Greensboro and after living with other people for several years, he appreciated the privacy.

“Sometimes, you got to take what you can get until you can do better,” he said with a smile. “(Avalon Trace) was heaven for me because it was mine.”

It’s a common sentiment among many residents of substandard housing, said Sel Mpang, a community engagement associate at the coalition.

“One of the things I’ve learned ... is you have to be very sensitive about people’s living situation,” she said. “Because even if that home can be in the worst condition for anyone to live in — and you’re wondering how is this OK? — if you report it to code or get the landlord involved, the house could be condemned. Then where would they go?”

“A lot of people fear losing their only home,” she said.

That’s especially true of families who come to Greensboro from countries such as Haiti, Liberia, Mexico and Vietnam. New to the country and often facing a language barrier, immigrants can be particularly vulnerable to getting stuck in substandard living conditions.

Mpang, a Vietnam refugee who came to Greensboro with her parents when she was 6 years old, experienced that firsthand.

“When we came to America, the homes we lived in, they had mold,” she said. “I didn’t have asthma, but I’m thinking it was a situation where maybe my parents didn’t know mold could cause that.”

In fact, she found during canvassing that many residents don’t make the connection between their housing conditions and their family’s health.

“This is a pattern, a recurring reality for people who live in this area,” she said. “Some of the parents, it’s so normalized, some of the things they have to face day to day. It becomes part of their routine, so they don’t know what’s beyond that.”

Partnerships helped identify ‘asthma hotspots’

In 2014, the Greensboro Housing Coalition partnered with the local health system, Cone Health, and the University of North Carolina-Greensboro (UNCG), and formed the Asthma Partnership Demonstration Project. The project focused on reducing home-based asthma triggers.

The coalition also applied for a Community Centered Health grant from the Blue Cross Blue Shield Foundation of North Carolina to conduct outreach.

In 2017, community activist Sandra Williams, from left, Josie Williams of the Greensboro Housing Coalition, and then Center for Housing and Community Studies at the University North Carolina-Greensboro Director Stephen Sills examined asthma hot spots in Greensboro, North Carolina. Josie Williams is now executive director of the Greensboro Housing Coalition. PHOTO COURTESY UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA-GREENSBORO

When canvassing, they regularly heard the name “Avalon Trace.”

By 2015, the asthma project’s partners were able dig deeper beyond the anecdotes.

Stephen Sills, a former professor at UNCG, founded the university’s Center for Housing and Community Studies. (Sills is currently vice president at the National Institute of Minority Economic Development’s Research, Policy and Impact Center.)

After applying for funding from a local philanthropic group, the Community Foundation of Greater Greensboro, Sills was able to develop a relationship with Cone Health, which gave the university access to its data.

When Sills mapped the addresses of emergency room visitors with asthma issues, Avalon Trace was identified as an “asthma hotspot.”

That data translated to extremely substandard housing conditions that researchers were able to document in person.

“People had roofs that needed repair, sewage that was backed up, broken windows, no door seals, gaps in the walls between window units that were 2-3 inches wide – all of the things that cause there to be hot, moist, wet and pest-infested units, all of which are bad for respiratory conditions,” Sills recalled.

“Pest infestations were really the worst thing,” he continued. “When the new owner went into the place and started ripping through the walls, (roaches) were crawling. There was water that would come in whenever it rained; one resident had a swimming pool they would set up whenever it rained. We had units where you would flush the toilet and it would come back out into the bathtub. No ventilation in the bathrooms, so (they) had serious issues with mold.”

Seeing the conditions firsthand humanized the problem and motivated coalition partners more than numbers ever could.

As Williams put it: “Data just isn’t enough. You need the qualitative to mesh with it.”

Resident voices led the way

New Hope Missionary Baptist Church has been a staple of the east Greensboro community since 1968.

But even though it was a walk up the road from Avalon Trace, Reverend Walter Richmond, Jr., said he and others at church struggled to communicate with residents about their health and housing conditions.

In addition to his work helping Avalon Trace residents, Minister Walter Richmond has spent time canvassing the neighborhoods of Haitian immigrants to help them transition, and he has worked on community violence issues. TALIS SHELBOURNE/MILWAUKEE JOURNAL SENTINEL

Some residents were suspicious and didn’t want to talk. Some were refugees who were happy to have a home in their new country and didn’t speak the language. And some simply didn’t live there long enough to complain; only one-third of the residents remained from when the church started conducting outreach eight years ago, Richmond said.

Hoping to reach deeper into the community, Richmond formed the New Hope Community Development Group and used space adjacent to the church to hold events where residents could voice their concerns.

That’s where Richmond and Jamilla Pinder, the assistant director of healthy communities at Cone Health, started to hear stories like Smoot’s.

Percy Dickerson, an 80-year-old Vietnam veteran and deacon at the church, was present at some of those meetings.

“The community would be there raising holy hell,” he said, chuckling at the memory.

Jamilla Pinder, assistant director for healthy communities at Cone Health, is also trained as a community health worker and community engagement specialist. TALIS SHELBOURNE/MILWAUKEE JOURNAL SENTINEL

Dickerson, an Avalon Trace resident, witnessed for years how previous ownership would refuse to spend any money on the building despite obvious signs of deterioration.

“They wouldn’t fix nothing,” he said. “They was just collecting rent.”

With a wealth of anecdotes and data, the coalition reached out to the property's owner — an out-of-state Georgia-based landlord — hoping they could work together to improve the complex.

They got no results.

So coalition members next went to city council members and local media to expose conditions in the building.

The coalition also encouraged tenants to file code violation complaints with the city’s Minimum Housing Standards Commission. Eventually, the number of complaints involved at least 50 units, Sills recalled, a threshold that allowed the commission to put a lien on the mortgage.

“If they didn’t fix these properties, the city would fix these properties and charge the owner,” he explained.

In response, the owner put the complex up for sale.

Percy Dickerson, 80, is a Vietnam veteran who has lived in the apartments since 1999. He said the previous owner never made repairs. Since the new owner took over, however, his bathroom has been revamped and several kitchen appliances were installed. TALIS SHELBOURNE/MILWAUKEE JOURNAL SENTINEL

The coalition worked with Collaborative Cottage Grove to find new financing and a new developer. It applied for a grant from the BUILD Health Challenge, a national coalition of health insurers, philanthropists and community organizations that award local agencies money for health equity initiatives. After securing the grant, Cone Health matched it. The parties worked to obtain additional private funding and a committment from the Community Foundation of Greater Greensboro to provide $1,500 per unit for renovations.

“That (was) enough for the new owner to rehab the property,” Sills said. “It allowed for a new metal roof. Tearing out old carpeting and putting in laminate floors. Painting interior and exterior, landscaping, digging up the old sewer lines and replacing them. Rehabbing bathrooms and kitchens. So many units were improved.”

Coalition brings system changes, but work remains

Since Cottage Gardens’ rehabilitation, groups in the area have continued to advocate for improvements in health and housing.

For example, Williams said, she wants to see funding for remediation set aside in the Guilford County School system.

“We appreciate the behavioral education you’re doing (in the school system), but if your plan doesn’t have a remedial component, all you’re doing is educating people and putting them back in an environment that’s literally making them sick,” she said.

The coalition still maintains a relationship with Cone Health to pinpoint asthma hotspots.

Greensboro’s Collaborative Cottage Grove was the recipient of a Build Health Challenge 3.0 grant. The collaborative is working with the coalition to target 15 families struggling with asthma.

“We set aside funding to make sure we can do remedial efforts,” said Tiarra Brown, the director of community engagement at the Greensboro Housing Coalition. "With those funds, we can say, 'We fixed this in the home, versus giving you a medical diagnosis but not changing anything in the environment that was triggering your asthma,'” Brown said.

The coalition also made gains in policy.

After Avalon Trace was rehabilitated, the city hired a new code enforcement director, who has hired more staff and created a searchable database of addresses with code violations.

“He has been a champion and a person who really gets it at a different level,” Williams said. "He started changing how his staff communicates out to the public. He made it better.”

She also said the coalition, which has its own certified housing inspectors, works closely with code enforcement to increase capacity.

Williams said the relationship with Cottage Gardens' new owner is much better. She has her phone number, and they stay in regular contact to address residents’ concerns and ensure conditions are steadily improving.

Ultimately, Williams said residents are much more informed and engaged.

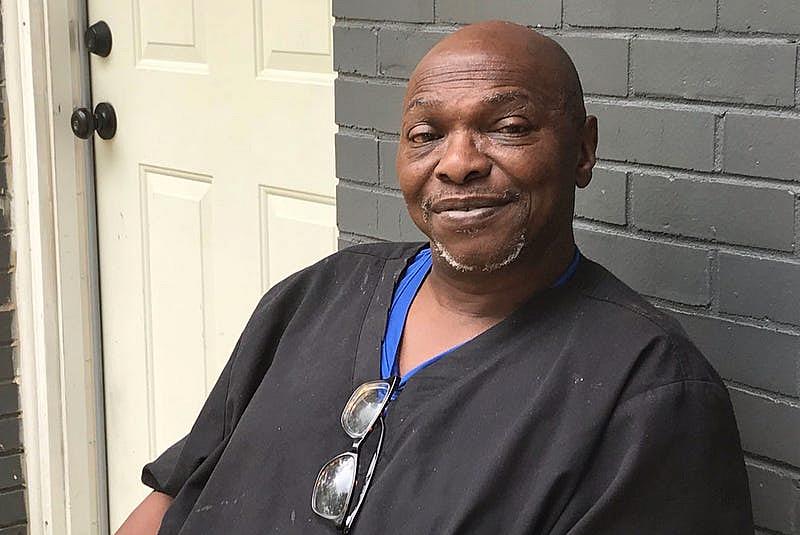

Stephen Smoot, 69, said when he first moved to Avalon Trace, the place was “trash.” Although he is grateful the new owner has made some repairs, he hopes existing tenants are the first to receive upgrades over vacant units or new tenants. TALIS SHELBOURNE/MILWAUKEE JOURNAL SENTINEL

“When we started Cottage Grove, there were four partners and two community members at meeting(s),” she said. “Within 30 days, we had 10 community members, and in the first six months, we had 10 partners. We’re roughly at about 15 organizations (now).”

Smoot was one of the residents who benefitted from those meetings. He calls Williams an angel for helping educate tenants like him on their rights.

Since the new owner has come in, Smoot said, the majority of his bathroom was replaced, with a new toilet, sink, vanity and new flooring. The apartment has hardwood floors now, and he scrubs them with Pine Sol and disinfectants at least twice a week to keep things clean. When we interviewed him in June, Smoot was waiting on a new stove and refrigerator.

He said he’s grateful some repairs have been made. However, he said, work remains.

When he turns the tub on, the initial gush of water still comes out red. He has managed to keep the roach problem “tolerable,” though he said they’re still in the walls. And he’s hoping the place will finally receive a fresh coat of paint.

He said he plans to buy a co-op once he saves up enough money.

Meet the team- Reporter Talis Shelbourne

- Editing Thomas Koetting

- Photos & Video Angela Peterson

- Data & Graphics Daphne Chen and Bill Schulz

- Digital Production Jordan Tilkens