Access Denied: Going digital should open more records to the public

Proclamations aside, the digial revolution has yet to liberate key sources of records.

Writing a letter to ask an agency that they grant you access to something as basic as the number of infectious diseases reported by county should be a thing of the past.

But it’s not.

Lawsuits against physicians – and anyone else – should be easily available.

But they’re not.

I noted in my last post that The Des Moines Register recently took a strong editorial stance against the lack of open access to records. In this post, I’m going to continue highlighting some of the ways the promise of open access has been thwarted, despite the arrival of new technologies that should put records in the hands of more reporters and engaged citizens.

One huge problem is when online access is provided only to the privileged few.

The digitization of public records has been a boon to reporting, and it should provide a boost to an engaged democracy as well. But turning paper into digital files is not the same as making them freely available online. The Register’s editorial board focused on Iowa’s online court system, which only allows lawyers to get access to the records remotely.

One of the most egregious examples nationally remains the access restrictions placed on the National Practitioner Data Bank. Here in one spot is every violation committed by a health care professional – at least those that have been reported. Hospitals and medical providers can get access. And yet no patient can get access. No reporter can get access.

When reporters are allowed to analyze the data from the data bank – data with no names attached – and when they actually use the data to connect the dots to physicians, they are threatened by federal officials. When even a single physician complains about how the database is being used, the federal government might take the whole database offline, as it did in 2011.

The Register editorial board makes a great comparison to the federal court system. If you go to a federal courthouse, all civil and criminal records can be searched and reviewed by citizens freely:

If they want to see those same documents on their home or office computer, they need only pay a fee — 10 cents per page, with a maximum fee of $3 per document — and even that fee is waived for people who view no more than $15 worth of records over a three-month period.

I’ve highlighted the beauty of being able to get access to federal court records online before.

Jonathan Starkey at the Wilmington News Journal in Delaware, for example, used the records to investigate Blue Cross Blue Shield of Delaware. The insurer had been paying a claims management company incentives to deny people access to care. Starkey told me:

We frequently ran searches through the PACER system of the federal courts to see if insurance companies were facing lawsuits about denials elsewhere in the country. That produced a story about a Nevada woman suing Blue Cross' contracted claims reviewer, a Tennessee-company called MedSolutions, for denying a test for her husband. He died of a heart attack some months after the denial.

That’s a great use of federal court records. And wouldn’t it be nice if more records were as easy to access as those? Access should not be granted only to a privileged few.

I’ll write next about the many ways reporters and others could make better use of death records – if they only had access to them.

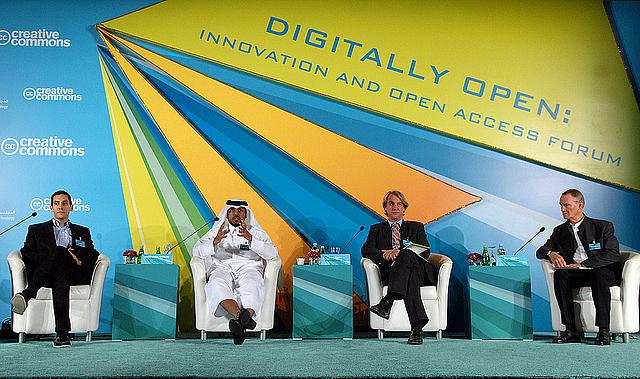

[Photo by ictQATAR via Flickr.]

Related post

Access Denied: Government secrecy should be hot topic among presidential candidates