Five hard-won lessons from reporting on what domestic abuse does to children's brains

Latrelle Huff prepares dinner for her children. (Photo: Stephen B. Morton/USA TODAY)

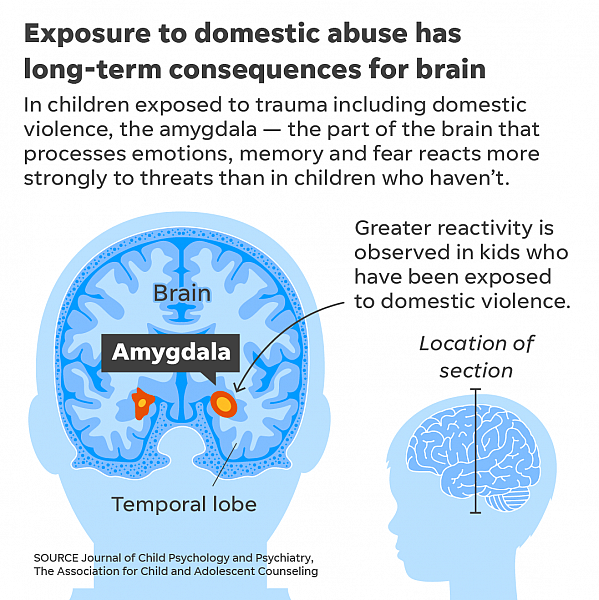

Applying and getting the Center for Health Journalism’s 2018 National Fellowship was the easy part. The hard part for myself and partner Jayne O’Donnell was following through with our ambitious project about children and domestic abuse for USA TODAY. We first wanted to do a series on how family court forces children to spend unsupervised time with allegedly abusive parents. But through a series of conversations with our editors, we decided to instead focus first on how new research shows exposure to domestic violence harms children’s brains, even if they aren’t the intended victims of the abuse.

One of the first lessons we learned was the need for patience with survivors. We were often asking people to relive their trauma when we interviewed them and that carried a high emotional cost for families. For those families who are still enduring the abuse, the feelings were especially raw. We had to be patient, kind and generous with them. It took time to get to hear their entire story and oftentimes there were a lot of tears. Being caring, empathetic and gentle was a must. In many of the video interviews we did people broke down crying and we often had to wait until they collected themselves before we could continue interviewing them. We even had one teenager storm out of an interview because the questions we were asking were potentially triggering. One of the mothers that I spoke with told me, in a fit of anger, that the questions we were asking were retraumatizing her. As we moved forward with interviews, it was imperative to let the families know that we would go at their pace and anytime they needed to stop that was fine.

A few more takeaways from our reporting:

Work with groups who care about your reporting. We worked with an advocacy group, the Center for Judicial Excellence, to find several of the families that we interviewed. That saved us time by introducing us to people who wanted to go on the record to tell us their story. The downside is that they had high expectations in what they thought our story would do for their lives. Some families wanted us to be a mouthpiece they could use to call their former partner names. We had to patiently explain that we have journalistic standards that prevent us from maliciously targeting people. In hindsight, I would have explained to each family that we have several editors who are going to weigh in on our project and that we can only tell one specific story. I often tried to tamp down their expectations and explain how the journalism process works. But I should have explained that more fully from the very beginning because it was hard to see their disappointment when we couldn’t include all the details of their stories in the final project.

Even if you don’t have an engagement grant, think about how to build a community. While we were working with the Center for Judicial Excellence we also launched a Facebook group, “I Survived It,” that was for people who were overcoming trauma. We knew when the story was published that we already had a community of engaged readers who would care about the work we had done. Those connections paid off because the biggest sharers of the story were domestic and sexual abuse organizations who were invested in the work we were doing. I’m proud of this fact, because it’s the people involved in these advocacy groups who are most impacted by our research. And when people reached out and asked how to connect with us, we let them know we had a group that they could join.

Get organized and have a plan. We wasted so much time, mostly because we started with anecdotes and didn’t have the research to back up what families were telling us. But we should have started with an outline of how we wanted the final story to look at the beginning of our reporting. Without a clear plan, we weren’t as focused as we should have been and often had to change the trajectory of our reporting. We also had editors that were busy with other stories in addition to ours, but it was incumbent upon us to push for more clarity and discrete goals. This is where I stress a key point: Make sure you are communicating with everyone involved in this project. Jayne and I were often trying to fit time in to talk and plan around our busy schedules; in hindsight we needed to set up weekly meetings to meet and work on the project. When it came time to work with our video and graphics team, it was hard to make sure all of the moving pieces of our project were coming together because not everyone knew what was happening with our project.

The journalism industry is shaky; have a backup plan. USA TODAY was dealing with layoffs and a hostile takeover bid while we were reporting on our story. The threat of layoffs distracted us and delayed our reporting as well. It may sound cynical but you need a plan in case you are laid off or an editor gets fired or quits. We didn’t have that in place and as a result we had plenty of chaotic moments when we struggled. Again, that’s why communication and weekly meetings are important to discuss any problems that might arise.