Five key tips for when you need to request a lot of public records

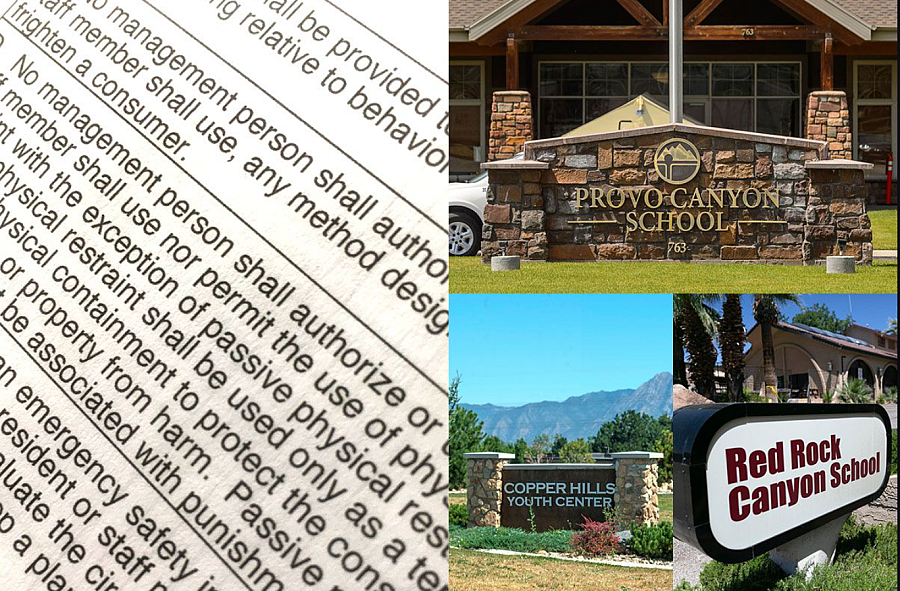

It’s easy to get overwhelmed when reporting on Utah’s massive for-profit “troubled teen” industry. First, there’s so many youth residential facilities here — nearly 100 dot the state, ranging from small seven-bed homes to massive facilities that take in hundreds of vulnerable children each year. And secondly, states from all across the nation have paid millions of dollars in government funding to send their most challenging children to Utah.

When I started reporting on my project for USC Annenberg’s Center for Health Journalism Data Fellowship, I knew right away that to cover this huge industry, it would take a large number of public records requests. That I would have to ask every state in the country how much money they spend sending kids to Utah through Medicaid funding, its juvenile justice systems or through the foster care system. And to try to figure out whether these facilities kept children safe, I knew I would have to file requests with every local police department that had a youth residential treatment center in its jurisdiction.

With all that ahead of me, I wasn’t sure if it was realistic. But a year later, I’ve filed more than 150 records requests and counting. It’s the first time I’ve ever taken on a project of this size, and I learned valuable lessons along the way about the best — and worst ways — to tackle a daunting list of records requests. Here are a few tips that might help other journalists who are juggling their beats and breaking news while pursuing that big project.

1. Keep track of your work.

I’ve never been very organized, but that had to change with a project of this size — my previous system of putting Post-it notes in random places around my desk just wasn’t going to cut it. Instead, I created a spreadsheet where I could keep track of which records I had requested and what the status of the request was. It was not complicated, and only had five columns: The agency that I requested from, the date of the request, who I sent the request to, what records were being sought, and what the outcome was.

This helped me not just in figuring out which states to follow-up with if I didn’t get a response, but it also let me quickly get an idea of what progress I’ve made and how close I was to having enough data for a story. The spreadsheet also helps if a huge news event, such as a global pandemic, pulls you away from a project for a sustained period of time. It was easier to jump back in when I had the time because I had diligently been keeping track of what records I had and what I still needed.

2. Ask for help.

It became clear pretty early on that I would need to lean on other journalists to help with my records requests. I asked a friend of a friend in Arkansas to put a records request in for me, because the law there requires that a requester be a resident of that state. I did the same with a journalist based in Bermuda. And I had a friend in Alaska share his data with me when I was concerned my own request was too limited. I was a little nervous at first about asking for help, because I know how busy journalists are. Filing records requests for other journalists is not how most people would want to spend their work days. I tried to ease that burden by crafting the language, so they would only have to push send. No one hesitated to do this favor, rather, they were eager to see what records came back — perhaps there was a story in there for them, too. Given that we were all local journalists and our audiences were spread so far from one another, I was fairly confident that I wouldn’t be scooped by asking for their assistance.

3. Streamline the language of your requests as much as possible.

The most embarrassing error I made during this project was sending a records request to the state of Texas asking them how much money was spent sending children from Hawaii to Utah. It was an error made simply because I had been using a form letter and hadn’t changed every reference from “Hawaii” to “Texas” before pushing send. This could have been remedied either by a more watchful eye, or by making the records request slightly more generic. Instead of asking for, “Any contracts between Texas Health and Human Services and any Utah-based youth residential treatment center regarding out-of-state placement of Texas youth,” I could have instead asked for “Any contracts between your department and any Utah-based youth treatment center regarding out-of-state placements of youths in your state.” Doing it this way would not only have saved me time, but also an embarrassing reply to confused Texas officials.

4. It’s OK to do a little at a time.

There were some days where I would sit down at my desk, put my headphones in, and send 20 or more requests in a day. Those days sucked. I found I was more productive if I could set aside a few hours a day to send five or 10 requests out. I personally felt like the morning was more productive for me, because I could get requests in before breaking news began to dictate my workload. But even dedicating just 15 or 20 minutes daily or every other day to push out a few requests is a way to keep chipping away at that larger project, while still meeting the demands of the newsroom. It’s easy to get overwhelmed by how much is left to do, but focusing on small goals helps.

5. Don’t be afraid to show your work.

After the records arrived and the story was written, I worried that someone would question how we arrived at the conclusions that we did. How did she calculate a per-bed violence rate? How did she know how much money Alaska spent, but not Mississippi? Rather than muddy up my main copy explaining how Mississippi and others didn’t respond to my records requests, I adopted a practice I had seen at ProPublica and elsewhere. I included a “How we reported this story” explainer at the end of the main story that detailed the records requests I sent and how we calculated the rates used for the story. I worried a little that it would be seen as bragging, but it was well-received by readers who appreciated understanding all the behind-the-scenes work that went into my reporting.

**