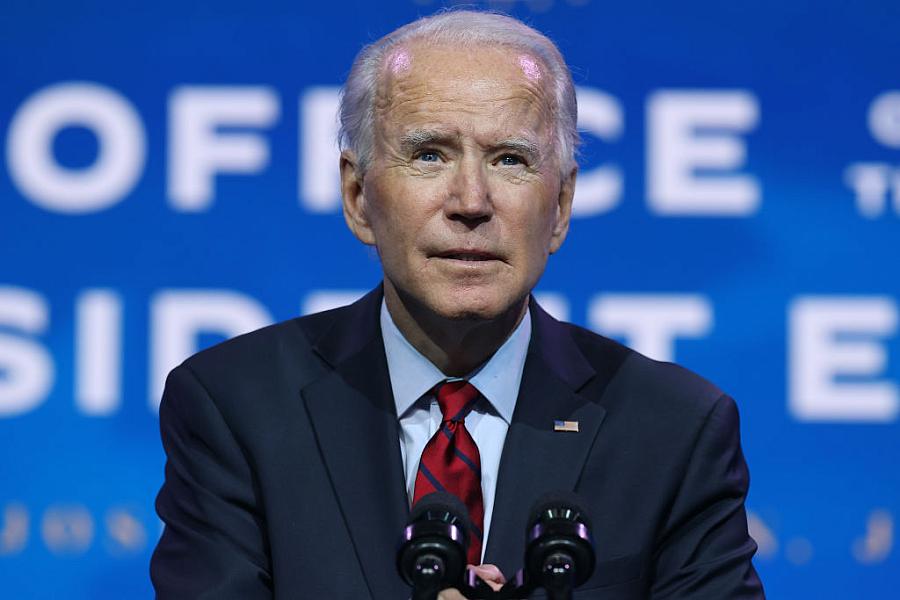

Here’s what 8 top health policy voices say Biden should do this year

(Photo by Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)

For the last decade, or so at least until the pandemic hit, the dominant health care storyline has been the push to get more people covered under the health insurance tent, an effort that slowed a few years ago. As we begin a new year with health and medical news still largely focused on the coronavirus pandemic, it’s a fair question to ask: What should be at the top of the health care agenda in 2021? I put that question to eight health care experts. Here are the fixes at the top of their wish lists, which also provide a useful guide for journos looking for fertile ground to explore this year.

Dr. Georges Benjamin, executive director of the American Public Health Association, put “building a modern, functional and real-time information technology infrastructure for the public health system” at the top of his list. He explained that the current public health technology infrastructure has been underfunded and is “terribly antiquated.” A new such a system would allow public health care data systems to talk to each other and share information. Benjamin noted that today data systems are not interoperable and disease surveillance systems are spotty and often incomplete. As an example, he pointed out many local health departments often still rely on paper-based recording systems and fax machines to exchange information. He called a new system a “best buy” that would “do the most to improve informed decision-making.”

Dr. Robert Berenson, senior fellow at the Urban Institute, noted that “financially enticing or requiring the states that haven’t done so to expand their Medicaid programs would be the most important.” A dozen states have yet to adopt the Medicaid expansion, including massive population centers such as Texas and Florida. On the delivery side, he said, “the federal government needs to develop price regulation models and incentives for states to limit prices that hospitals negotiate with commercial insurers. In the past 20 years hospital prices have increased from 110% of Medicare to 24% of Medicare, producing “unconscionably high levels of cash and investments maintained by nonprofit hospitals.”

Dr. Michael Carome, director of the Public Citizen’s Health Research Group, suggests that to better ensure the safety and effectiveness of drugs and devices approved by the Food and Drug Administration, Congress should enact a firewall between the FDA staff who interact with industry reps seeking FDA approvals and FDA staffers who will be involved in actual reviews of drugs and devices. “The current system of interactions with sponsors has the potential to undermine the integrity of the agency reviews,” Carome said.

Lanhee Chen, the David and Diane Steffy Fellow in American public policy studies at the Hoover Institution, hopes the Biden administration will make permanent some of the telehealth changes begun in the Trump era by executive action. Such changes made it easier for providers to furnish telehealth services such as diagnosing mental illness across state lines, and to provide such services at federally qualified health centers and rural health clinics. The Trump changes also increased the range of health services covered by Medicare. “Without further action, these reforms will go away,” Chen said. “They would garner bipartisan support and be pretty easy to do, in my mind.”

Timothy Jost, emeritus professor at Washington and Lee University, said his top recommendation for the Biden administration would be to rescind the Medicaid waivers granted by the Trump administration, some of which impose work requirements on Medicaid recipients. The legality of such work requirements is now before the U.S. Supreme Court, which will hear the case later this year. Jost would also like to see Tennessee’s Medicaid block grant rescinded as well. Under a block grant arrangement, the government gives the state a set amount of money to use for health benefits. When the money runs out, low-income residents get no more benefits. Compare that with Medicare, in which all residents who qualify are entitled to a benefit. Block grants are likely to result in fewer people receiving benefits and reduced federal spending, which is why they are popular with some politicians. They save money.

Gerald Kominski, professor of health policy and management at the UCLA Center for Health Policy Research, says the most important reform would be to expand the Medicare program to Americans age 60 and older instead of using age 65, the current age for eligibility. “This is the step the original architects of Medicare expected to happen in the 1970s. Fifty years later I think it’s time to take the next step in that original design and to start expanding Medicare to the rest of the population.” President Biden has voiced support for such a plan, which faces strong opposition from hospitals.

Jonathan Oberlander, professor of health policy and management, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, says the list of needs “is so long — there is so much they need to do.” He said if the administration had a magic wand he would “want them to wave it and achieve universal health insurance. It’s hardly magic. Every other rich democracy, after all, has it.” In a category Oberlander called “aspirational,” he would entice the “hold-out” states to expand Medicaid. And in the category he labeled “possible legislatively,” he suggested making the Affordable Care Act more affordable through enhanced premium subsidies.

Edwin Park, research professor at Georgetown University’s McCourt School of Public Policy, says one of the country’s top health priorities should be to reverse the losses in children’s health insurance coverage, citing some alarming stats. Between 2016 and 2019, the children’s uninsured rate climbed from 4.7% to 5.7%. Those numbers translate into an increase of about 700,000 children without coverage and presumably without regular access to care. Park believes that number has probably gone up over the past year because of job losses and loss of health coverage during the pandemic. He noted a number of policy options that could reverse this trend. They include making it easier to enroll kids and families in public coverage, increasing the federal Medicaid matching rate to avert state budget cuts, increasing outreach and enrollment efforts, and reversing federal policies such as the public charge rule, which have had a “chilling effect” on Medicaid participation among children eligible for the program in immigrant families.

This health policy to-do list is long and challenging, and perhaps unachievable in its entirety. But the way I see it, how much of it the nation can accomplish will define the kind of country America will be. We have a long way to go before America can claim it has the best health care system in the world.

Veteran health care journalist Trudy Lieberman is a contributing editor at the Center for Health Journalism Digital and a regular contributor to the Remaking Health Care column.