How data revealed a hidden narrative about black male suicides in Texas

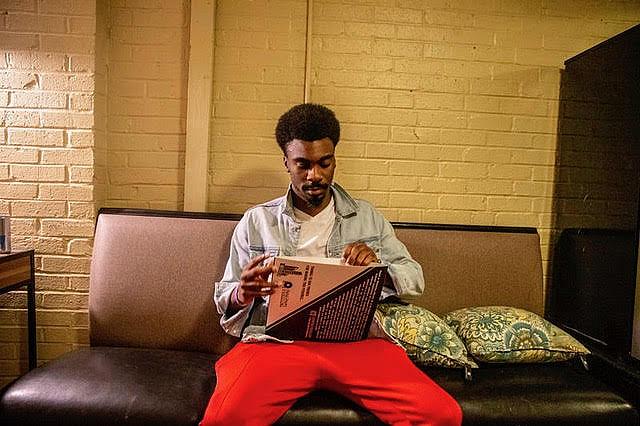

The author’s series featured the story of Tye Harris, a 24-year-old up-and- coming rapper and a suicide survivor.

Shaban Athuman/Staff Photographer

Too often within communities of color, issues of mental health and suicide don’t receive the attention they need.

Perhaps it’s because it’s hard for youth of color to talk about the problem. Or, maybe, their families haven’t been able to really understand why they happen. For my recent data journalism project, I wanted to look into issues of mental health disorders and suicide within communities of color.

The project taught me a lot of valuable skills in data analytics, and reminded me how long connections to marginalized communities fuel important enterprise journalism. I learned a lot of lessons from my 2018 Data Fellowship.

Originally, the project’s pitch was to look at mental health issues within Hispanic populations, given the growth of the population in Texas and the polarizing immigration rhetoric. Youth survey data indicated that Latino high schoolers in 2018 showed increased rates of depression and anxiety.

But after analyzing data from medical examiners and death certificates, I shifted the project’s focus after the data showed a deadly and growing trend among both young black and Latino men. I found the suicide rate had grown faster for young black and Latino males in Texas over the last 10 years, according to an analysis of federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data.

While the numbers still trailed those of whites, our data analysis found that among black males 24 and younger there were 9.2 suicides per 100,000 people in 2017, the most recent year for which data was available, compared with a rate of 3.7 suicides in 2007. It was the most dramatic increase among demographic groups, with the suicide rate more than doubling.

For young Hispanic males, the suicide rate increased about 55% to 7.6 suicides per 100,000 over the past decade. Suicides by young white males increased by 43% to a rate of 15 per 100,000.

While mental health problems affect every demographic, these young men are more likely to live in poverty, experience trauma or be exposed to violence. And they are less likely than whites to seek help, experts say. The cost of mental health treatment adds another barrier to care.

Reporting on this issue was a challenge, but here are some lessons I learned.

1. Data is not all of the story.

Medical examiner data was helpful in showing how serious this public health is. Still, it was difficult to find human sources to bring the story together. There were virtually no nonprofit organizations working on suicide awareness that were led by families of color in Dallas. Although medical examiner data included names of those who died by suicide, it was often hard to find families. In many cases there were no obituaries. I also felt that the perspective of the broken-hearted family who had to deal with such trauma was a narrative too often shared in existing reporting.

I felt it would be more empowering to tell the story through the lens of a suicide survivor. It would be a way to show a person’s journey — how they learned how to cope with trauma, anxiety and depression. And it’d be an example to many of how life with depression can get better.

When I was hired at The Dallas Morning News, I made it a priority of mine to connect to communities that were underrepresented in news coverage. Specifically, I wanted to seek out positive stories from poor black and Latino neighborhoods.

The sources I developed helped me find the story of Tye Harris, a 24-year-old up-and-coming rapper out of Oak Cliff and a suicide survivor.

2. Make organization a priority while managing a demanding daily beat.

I was promoted about a month into my project to the public safety beat, which meant covering the Dallas Police Department and criminal justice issues.

It was an exciting opportunity for me, but inserting myself into a new beat with high demands meant I needed to stay organized on my long-term project. I made organization a priority in this project, keeping my data journal up to date and making sure I wrote notes to myself to stay on track. I wrote a detailed reporting plan that listed a few people to talk to per week, so I could chip away at the project.

Sometimes, one or two weeks would pass after busy breaking news days before I could get back to my project. When I looked back at my notes, it was so helpful to know exactly where I left off instead of trying to guess.

I kept a spreadsheet of data requests, with status updates and notes after interviews with the folks who maintained data. The data journal was meant to keep notes on my analysis but the spreadsheet was also important to know what the experts or data keepers said to make sure my analysis was on the right track.

3. There’s real impact in community engagement.

The story received a lot of reaction through social media comments and emails after it was published. Our local NBC station featured the story on their newscast. The public radio show Texas Standard invited me to their show, which helped expand the audience to the whole state.

Messages from readers started to pour in shortly after it ran. A man who works with Latino youth in West Dallas said the story inspired him to start talking about mental health within his nonprofit. Another man who grew up in Southern Dallas said he liked how the story showed “how a man of color copes via hip hop.”

The most rewarding part of the community engagement experience was when we hosted our town hall. I brought the reporting on the issue to a predominantly black neighborhood in southern Dallas, inviting some of the sources who helped with the story for a community town hall meeting on mental health. For the event we partnered with For Oak Cliff, a nonprofit organization that works on racial equity issues in Oak Cliff, and we received a large turnout, with parents and children attending. People within the crowd shared their personal stories and got to ask questions from a psychiatrist, Dr. Brian Dixon.

The best part? Many wanted to see The Dallas Morning News host another event.