How we reported on California’s failure to protect addicts at rehab centers

Every day people die in unlicensed, unregulated sober homes, and California doesn’t even bother to count the bodies.

I first learned about this issue in the spring of 2018. I was listening to a podcast with a therapist in Florida who was talking about how that state’s new laws regulating rehab facilities were driving unscrupulous operators to California. My team traveled to Southern California to learn more about what are known in the industry as “body brokers,” people who lure addicts with good insurance to come to California, stay in rehabs, and make millions off of their insurance. The catch? The rehabs prefer their clients test positive for drugs. In some cases, they’ll give addicts drugs before they arrive at the facility; in some instances, it leads to an overdose. We profiled a father whose son had overdosed before entering rehab for a story on this issue in 2018.

Shortly after that story aired, I applied for the Center for Health Journalism’s 2019 California Fellowship. I wanted to use this grant to give parents and families more information about rehab facilities. They deserve to have transparency in this field, so they are able to make educated decisions with their loved one. Right now they do not have those tools.

Two careful distinctions need to be made that most people, even some lawmakers, do not understand. There are two kinds of rehabs, licensed and unlicensed. Most people do not think to check to see if the facility they’re sending a loved one to is regulated by the state. Licensed facilities are overseen by the California Department of Health Care Services. We’ve found hundreds of cases of people dying in these licensed facilities.

Unlicensed sober homes pop up all of the time, they are not tracked by the state of California, and they are not held accountable by any government system.

I put in public records requests with the Department of Health Care services for records of all of the deaths that have happened at licensed rehab centers. It took the department an entire year to fulfill this request. It revealed hundreds of instances of people dying in rehab facilities, and it proved people operating these businesses were not following state protocols, which could have prevented many tragic deaths.

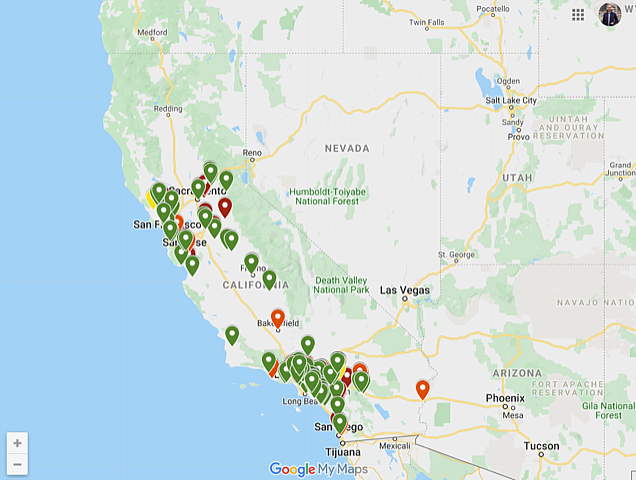

I took these records and turned them into an interactive map for part one of this series. Whenever a death happens at a rehab facility, the state has to conduct an investigation and determine if there were any deficiencies there. A class A deficiency indicates the rehab violated state protocol and put their clients in immediate danger, a class B deficiency indicates the rehab violated state protocol and may have endangered residents, and a class C deficiency indicates the rehab violated protocol and corrective action needs to be taken.

Next, we took our questions to Sacramento. We met with Assemblywoman Cottie Petrie-Norris and state Sen. Jerry Hill, who are part of a bipartisan group that worked on legislation this year to regulate the rehab industry. AB 920 would have forced all sober homes to be licensed through the Department of Health Care Services so they are held to certain standards.

We also met with an advocate, Wendy McEntyre, who has dedicated her life to reforming this industry. She lost her son to an overdose at an unlicensed sober home in 2004. Wendy helped point us to research the state commissioned back in 2012 highlighting this tragic problem. The report from the California Senate Office of Oversight and Outcomes concluded that the state “consistently failed to catch life-threatening problems” and showed “reluctance to shut down programs that pose a danger to the public.” It also found that other states require medical care to be provided inside detox facilities, while California doesn’t.

These facilities are expensive. We found the average stay for one month at a rehab in California can cost $40,000. Anne and Tim Russell spent that amount to send their son Teddy to Mountain Vista Farm, a licensed facility. He was in their care for less than 24 hours.

Teddy told Counselors at Mountain Vista Farm that he had taken Xanax and oxycodone earlier that day. Counselors allowed Teddy to go to his room and sleep, and did not perform critical, necessary steps to ensure Teddy’s survival. Detox centers must check on patients every 30 minutes for the critical first 72 hours, but that didn’t happen at Mountain Vista Farm. Seven hours after he was dropped off at Mountain Vista Farm, Teddy Russell was dead.

The state has the power to suspend a rehab facility’s license after a Class A deficiency. Teddy’s death turned up two deficiencies, but the state didn’t shut the place down. In fact, we’ve learned it rarely shuts any rehab center down. Instead the penalty in Teddy’s case was a $700 fine.

Public records show Teddy’s story is not unique. 190 people have died at other rehab facilities in California since 2010. We found dozens of deficiencies, from falsifying records, failing to report deaths, and employing unqualified staff to not monitoring patient vitals, as in Teddy’s case.

This is what goes on at licensed rehabs. But hundreds of unlicensed rehabs are operating around the state right now, with no regulation whatsoever. Wendy’s son died in one of those. AB 920, which was going to be called Jarrod’s Law after him, would have required all sober homes to be licensed and regulated. Unfortunately, it was vetoed by Gov. Gavin Newsom. “I am supportive of the Legislature's intent to license all SUD recovery and treatment services,” he wrote at the time. “However, developing a new licensing schema is a significant undertaking, and would require a significant departure from the bill as enrolled.”

This reporting has opened my eyes to what happens when a stigmatized, captive, audience lacks appropriate advocates. This predatory industry is thriving, and more people are dying every day. There’s much more work that needs to be done to track rehabs, and protect vulnerable people suffering from addiction in California.