How well are Medicaid plans taking care of kids? It’s a frustrating black box

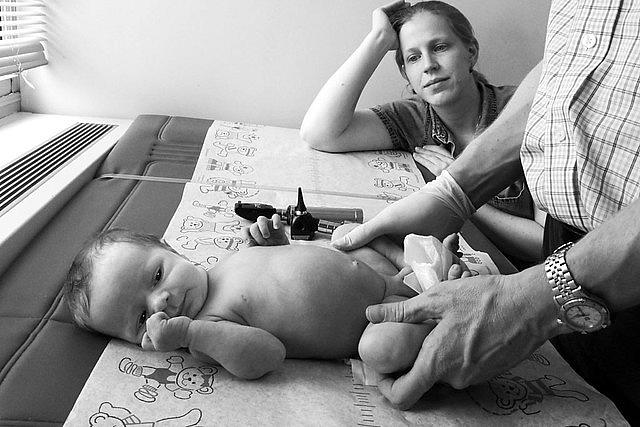

Around the time of his first birthday, D’ashon Morris had developed a dangerous habit: pulling out the tracheostomy tube he needed to breathe. As The Dallas Morning News reported last year in a series of stories detailing problems in Texas’ Medicaid managed care program for foster children and adults with disabilities, D’ashon’s Medicaid managed care organization denied repeated requests from doctors to pay for the intensive nursing that the foster baby with severe birth defects needed.

Without that care, he pulled his breathing tube out when no one trained to treat him was nearby, and as a result suffered a devastating brain injury that left him in a vegetative state.

The Dallas Morning News series does a thorough job of explaining why and how Texas’ system fell apart and allowed this tragedy to occur, but the problems affecting millions of low-income kids in Medicaid managed care stretch beyond the state’s borders.

Nearly 35 million children are enrolled in Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program, and in 39 states and the District of Columbia, the vast majority of low-income kids and most everyone else enrolled in Medicaid receive their benefits through a managed care company.

Here's how Medicaid managed care works: Health insurance companies (whether for-profit or nonprofit) receive a set payment from the state Medicaid agency each month to deliver services to the beneficiaries enrolled in the company’s plan.

Within limits, if the health plan spends more on covered services than the amount it receives from the state Medicaid agency each month, the company absorbs the loss; if it spends less, it keeps the difference. The setup has grown increasingly popular with state officials because it promises predictable costs each month and can offer Medicaid beneficiaries better care coordination than they may otherwise receive in a more traditional fee-for-service arrangement.

Medicaid managed care can be highly lucrative for a health plan and its management, depending on monthly payment rates, the cost of creating an adequate provider network, and how much care enrollees use each month, among other factors. For instance, the plan that covered D’ashon Morris, Superior HealthPlan, is a Texas subsidiary of Centene, a Missouri-based for-profit managed care company that operates plans in 20 states, covers more than 6.1 million Medicaid beneficiaries (according to CCF analysis of the Kaiser Family Foundation’s data), and has a market capitalization of more than $22 billion (as of June 10).

Centene recently announced plans to acquire WellCare Health Plans, Inc. in a cash and stock transaction valued at $17.3 billion. If the deal goes through — and that’s a big if given that it has to be approved by state and federal regulators, as well as shareholders — the combined company would cover an additional 3.2 million Medicaid beneficiaries and offer plans in five additional states.

The care for these millions of people enrolled in Medicaid managed care is funded by federal and state tax dollars. But when it comes to how well the system is working, very little is known about how well any individual Medicaid managed care plan is delivering quality, accessible care to the children it covers.

About $307 billion in federal and state dollars flowed to Medicaid managed care companies in 2018, more than half of all Medicaid spending that year. However, the voluntarily reported quality data that state Medicaid programs send to the federal agency is aggregated by state, not reported by plans. That means it is next to impossible to find out how well a given plan is doing on ensuring its members receive high-quality care.

When it comes to how well the system is working, very little is known about how well any individual Medicaid managed care plan is delivering quality, accessible care to the children it covers.

Patients too have a near impossible time finding out any information about the quality of the providers they see when they’re enrolled in Medicaid managed care. As detailed in a blog series here last year, collaborators from the USC Health Data Accountability Project, a joint initiative of the USC Center for Health Journalism and the Gehr Family Center for Health Systems Science, tried to obtain and publish quality data for the clinic groups that serve millions of Los Angeles County residents covered by Medicaid. No one was willing to share, and state regulators and Medicaid managed care plans were not interested in making more quality data public.

There has been some movement in California to improve the transparency of managed care plans on care quality. Just this past April, researchers from the University of California at San Francisco presented their analysis of 10 years of quality data for each Medicaid managed care plan (MCPs) in California. The researchers ranked the plans by performance on quality metrics — including children’s access to primary care and immunizations — in 2017. "On average,” they concluded, “public MCPs and non-profit MCPs rank significantly better than for-profit MCPs."

Federal legislators too are beginning to ask questions about what’s happening in Medicaid managed care. Sen. Bob Casey, D-Pa., and five other U.S. senators requested that HHS Secretary Alex Azar closely monitor whether plans are meeting their transparency requirements. Senator Ron Wyden, D-Ore., ranking member of the Senate Finance Committee and Rep. Frank Pallone, chairman of the House Energy and Commerce Committee, sent CMS Administrator Seema Verma a similar letter asking CMS to “renew its commitment” to ensure children and other beneficiaries have access to the care they need.

It’s easy to get overwhelmed by these large businesses, with billions of dollars in revenue and byzantine health delivery systems. But at the core of these complex systems are children like D’ashon and his family who are trying to get the care they need to live healthy and full lives. We need to know much more about whether Medicaid managed care organizations are doing a good job caring for the millions of kids entrusted to them, and what taxpayers are getting for the hundreds of billions of dollars paid to managed care plans each year. As D’ashon’s story reminds us, the stakes couldn’t be higher.

Maggie Clark is a senior state health policy analyst at Georgetown University's Center for Children and Families. Andy Schneider is a research professor at Georgetown's McCourt School of Public Policy.