It’s hard to tell stories of real people dealing with STDs, but here’s why it matters

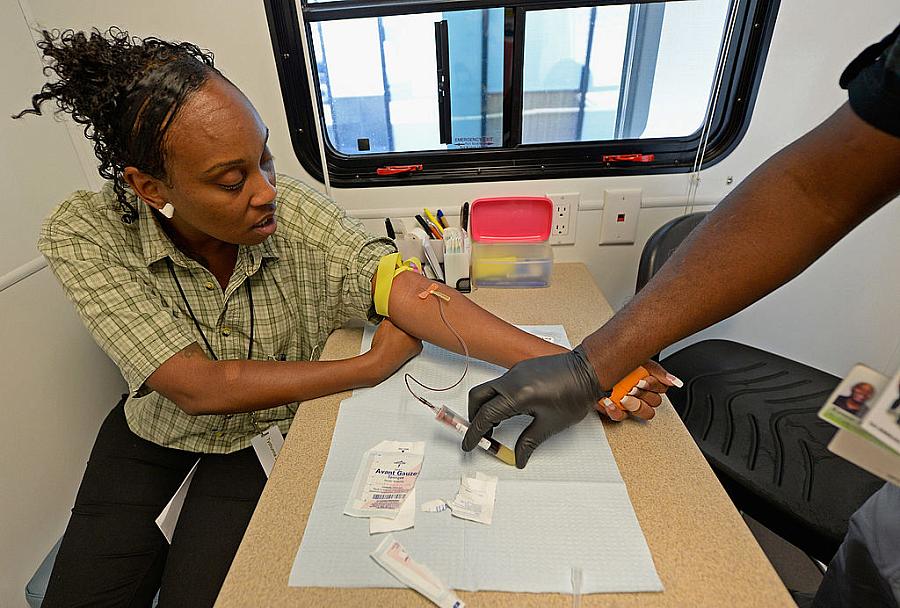

A woman has her blood drawn for HIV/AIDS and STD testing at a mobile clinic in Los Angeles. (Photo: Kevork Djansezian/Getty Images)

With reported cases of sexually transmitted diseases on the rise, some advocates have called on journalists to do more than report the alarming numbers. They want coverage that puts a human face on the problem.

“We don’t have a lot of stories of people talking about their personal experience with STDs, and we need that to make a difference in this field,” said David Harvey, executive director of National Coalition of STD Directors (NCSD), during a recent call with the Association of Health Care Journalists.

Publicizing the human impact of STDs could shift more resources to testing and treatment and quash hurtful stigma that discourages people from seeking care, advocates say.

But finding people who are willing to talk about their STDs publicly can be a tall order for journalists. Most STDs remain a topic that people are fearful to discuss, even as shame and embarrassment have diminished around mental illness, rape and HIV/AIDS. How many celebrities can you think of who have spoken out about their own STD?

My own informal scan of recent news stories about STDs yielded plenty of quotes from public health professionals and clinicians but few from average people with an STD.

Some journalists offered me their own insights on the difficulty of reporting personal narratives about STDs.

Susannah Luthi, a reporter at the trade magazine Modern Healthcare, said her reporting for a story about CDC screening guidelines taught her “just how insane the stigma is.” Luthi said she “lucked into” interviewing someone with herpes, because it was someone she knew who approached her about doing a story. The woman agreed to be quoted without her name being used.

Luthi said she spent time in STD-related chat rooms as part of her reporting and gathered anecdotes that didn’t wind up in her coverage, about people contemplating suicide after being diagnosed.

“I tried to find other people to talk to (on the record), and it was difficult,” she said.

The fact that people are so hush-hush about STDs is striking when you consider their ubiquity. Most Americans will have an STD or sexually transmitted infection (STI) — a precursor to an STD, when a virus or bacteria has entered the body but has not caused symptoms — at some point in their lives. The most common is HPV (human papillomavirus), which often goes away on its own without causing harm.

The fact that so few people are willing to share their stories “makes it a lot easier for people to dismiss people with STIs: ‘They are all promiscuous, dirty so-and-so's,’” said Jenelle Marie Pierce, who created The STD Project, a website that offers support and guidance.

But Pierce said stories that are rushed to print using only official sources can do a disservice, particularly if professional health educators and clinicians use language that comes across as sterile or preachy: “Just because somebody has an M.D. or Ph.D. doesn’t mean that they are empathetic or non-stigmatizing.”

Finding the personal angle can even be challenging for advocacy organizations, NCSD spokesman Matthew Prior said, who said it’s “a consistent battle” to find people who are willing to talk openly about their STD infection.

Bacterial STDs such as chlamydia, gonorrhea, trichomoniasis and syphilis can often be cured with antibiotics relatively quickly. “That makes it hard to kind of identify people who can be advocates or spokespeople for (those) STDs,” Prior said.

By contrast, STDs caused by viruses — such as HIV/AIDS and genital herpes — can’t be cured. “If something is going to be with you for the rest of your life, you might be apt to be more vocal about that,” Prior said.

Indeed, an activist community has begun to develop around herpes, which has long been sensationalized. In 1982 Time ran a cover story that declared herpes “today’s scarlet letter” and said the virus “threatens to undo the sexual revolution.”

These days reporting — such as stories about lawsuits filed against celebrities like Usher — can portray herpes as “this big terrible thing,” said Amanda Dennison, the NCSD’s director of programs and partnerships. “It’s not,” said Dennison, who recently wrote a blog post about her own herpes diagnosis. “It literally is basically a rash.” (It can pose more serious risks, particularly for pregnant women.)

Of course, some STDs have potential to do devastating harm, especially if left untreated. Gonorrhea, which has increasingly developed antibiotic resistance, can increase the risk of HIV transmission. Mother-to-child transmissions of syphilis can result in birth defects and death.

Further, there are disparities in who is affected. Rates of three STDs that are tracked at the federal level — gonorrhea, syphilis, and chlamydia — have been seen across demographic groups, but African Americans and people ages 14 to 24 have been disproportionately affected.

(Herpes is the most common STD, after HPV, but it is not among the three federally reported STDs.)

Several people I spoke to suggested that journalists begin by reaching out to the increasing number of activists who have gone public about their disease. Some examples:

- Pierce recently founded an international herpes awareness network, HANDS.

- Writer Emily Depasse opened up about her herpes diagnosis.

- Sultan Shakir, the executive director of SMYAL (Supporting and Mentoring Youth Advocates and Leaders), wrote about his experience contracting syphilis in Washington, D.C.’s Metro Weekly, an LGBTQ publication.

- Bustle published a roundup about activists using YouTube, podcasts and the web to open up discussion about STDs.

Other suggestions for journalists to humanize their coverage:

- Reach out to community-based organizations. Government-run public health departments may have “more hoops to jump through” in terms of connecting reporters to sources, Prior said.

- Approach people with respect and curiosity. “No source wants to feel as if they are being judged by the person interviewing them,” said Steph Auteri, a journalist who writes about women’s health and sexuality.

- Understand that people might fear social and economic repercussions if their name is used. Clearly spell out how their information will be used.

- Seek our inclusive organizations, which can be found via the National Coalition for Sexual Health.

- Explain that while factors such as anonymous sex, multiple sex partners, not using a condom, and being under the influence of drugs or alcohol while having sex may increase the risk of getting and STD, many people contract an STD without engaging in those behaviors.

- Consider your word choices. HANDS is working on a language guide for journalists that could be applicable to all STDs. It advises against language that is depersonalized or implies victimhood, such as “herpes positives,” “herpes sufferers,” and “herpes-infected.”

“The stigma gets in the way of the reporting,” said Salon writer Nicole Karlis, who also wrote recently about the stigma around herpes. “But there are some ways, and I think it's’ definitely important to bring a human side rather than just have a doctor talk about it.”