Researchers Seek Hepatitis B Cure as Trump Slashes Health Agency Funding

This story was originally published in the San Francisco Public Press with support from our 2025 California Health Equity Fellowship.

Dr. Maurizio Bonacini, a gastroenterologist at UCSF, is leading one arm of an international clinical trial seeking a cure for chronic hepatitis B.

Jason Winshell/San Francisco Public Press

The Trump administration’s efforts to slash medical research funding threaten progress toward a cure for hepatitis B. Its proposed budget calls for $1.8 billion in cuts to the National Institutes of Health and the elimination of all federal funding for the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities, along with additional cuts to the Food and Drug Administration, which has final say on approving new drugs and treatments.

Dr. Maurizio Bonacini, a gastroenterologist at the University of California, San Francisco, is directing one arm of a 72-week-long, triple-drug therapy study that backers hope will cure many patients of chronic hepatitis B. He projected that the B-United international trial, funded by GSK, formerly known as GlaxoSmithKline, could conclude by 2027. But if the trial is successful, Bonacini said cuts to the FDA’s budget, of 5.5% beginning next year, could delay approval of the potential cure for years.

“The FDA can give accelerated review, which takes less than six months. Otherwise it will be a year or two, so not before 2029,” he said.

The cuts are just the latest in a series of hurdles that researchers and clinicians face in managing hepatitis B infections in the United States. Public health efforts have focused largely on prevention rather than treatment, leaving those infected with few options beyond lifelong monitoring and antiviral medication. Despite years of investment from government and pharmaceutical companies, a cure has remained out of reach. Now, government funding is being slashed, and key research centers have shuttered. And while not all of the promising clinical trials will be affected by the cuts, researchers are struggling to enroll enough Asian American participants, the demographic most affected by the disease.

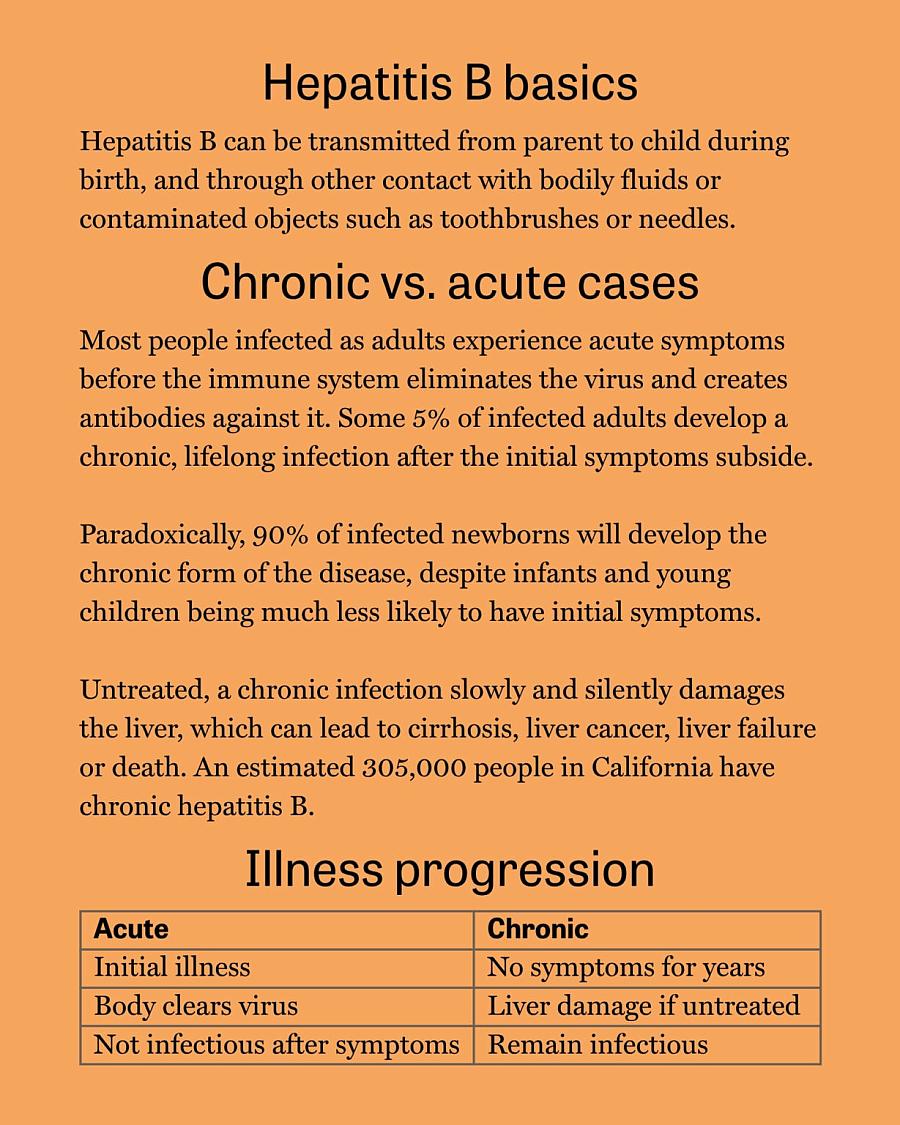

The hepatitis B virus has been afflicting humans for centuries; traces of it were found in a 16th-century Korean mummy. Today, chronic hepatitis B affects an estimated 305,000 people in California, with the vast majority of cases affecting people in Asian American and Pacific Islander communities. In the United States, about 1,700 people die from chronic hepatitis B complications every year.

Cure in trials

Sources: CDC, Mayo Clinic, and Heptology, Medicine and Policy

Now, researchers in the Bay Area and around the world are closing in on a possible cure. The B-United clinical trial, which is being conducted at more than 80 study sites across 18 countries, involves injections of two messenger RNA, or mRNA, molecules to reduce the amount of hepatitis B virus circulating in the patient’s body. Twenty-four weeks after the injections, a drug called Bepirovirsen is introduced. Bepirovirsen has been proven to cure about 10% of patients when used alone.

With the new protocol, “they expect a cure rate that will go from 20% at the lowest end to 50% of patients that have lower level of virus,” Bonacini said, “which would be huge in the hepatitis B world, because that’s never been seen before.” Researchers project that in cases where the protocol is effective, patients could see their risk for developing liver cancer cut in half.

People whose chronic hepatitis B is not cured by the new protocol will still be able to take daily virus-suppressing drugs, which have been available as a treatment since the late 1990s.

Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders at high risk

Globally, the danger of hepatitis B is well documented and deeply concerning. While viral hepatitis and tuberculosis are leading infectious causes of death, hepatitis B alone accounts for 83% of all viral hepatitis deaths, with an estimated 3% of the world’s population living with the infection, according to the World Health Organization.

In the United States, however, it’s not highly prioritized as a public health concern, “because it’s silent and because it impacts underserved communities,” said Chari Cohen, president of the Pennsylvania-based Hepatitis B Foundation.

A 2018 study estimated that 89% of chronic hepatitis B cases in the San Francisco Bay Area were among Asians and Pacific Islanders, despite this group making up 25% of the population. A 2023 study by CDC researchers found that in the U.S. about 50% of people with chronic hepatitis B were aware of their condition, an improvement over previous studies that found more than two-thirds of those with the illness did not know they had it.

Stigma, underfunding and other barriers to health care have stymied efforts to test for and track chronic infections. In response, organizers are working to reignite community-based outreach and health education campaigns.

Many researchers believe the high rate of chronic hepatitis B infections among Asians and Pacific Islanders is due in large part to parents unaware of their own infection passing the virus to their newborns. Chronic illness is vastly more likely to develop in those infected at birth than in patients who contract the virus as adults. In addition, vaccination rates in developing nations are low and screenings for acute hepatitis are insufficient to detect chronic disease.

Dr. Amy Shen Tang, director of immigrant health at North East Medical Services in San Francisco, oversees hepatitis B and C infections and tuberculosis exposure. She has specialized in hepatitis B in Asian American and Pacific Islander communities throughout her career.

Tang said the story of Dr. Mark Steven Lim illustrates how even medical professionals can be unaware of the unique threat hepatitis B poses to people in Asian American and Pacific Islander communities.

“He was an internal medicine physician and he found out he had hep B during his training, but was told it was not a big deal, and then developed liver cancer,” Tang said.

The physicians training Lim apparently assumed he had been exposed as an adult and that the virus would not become a concern until he was in his 50s. But his infection occurred when he was a child, and by his early 30s he had advanced liver damage.

Lim was about to start his medical career when he discovered he had only months to live. He died in 2002 at age 32.

Lim’s was one in a wave of deaths among Asian Americans in San Francisco that alerted local activists to the lurking danger of chronic hepatitis B infection. The shock of these losses sparked the launch of Hep B Free, a broad coalition of groups determined to raise awareness and take action to address the effects of hepatitis B. The coalition lost momentum in recent years and is working to regain ground in the fight against the disease.

Challenges to immunization

Also contributing to the overrepresentation of immigrants from Asia, the Pacific Islands and sub-Saharan Africa among those with chronic hepatitis B are varying rates of immunization around the world. A preventive vaccine became available in 1981. Many variations have been created that require the recipient to return for one or more booster shots. The federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s guidelines call for all U.S.-born infants to be vaccinated shortly after birth and return a few weeks later for a booster shot to prevent mother-to-child transmission.

UCSF’s Bonacini said many developing countries are unable to vaccinate all newborns and get them booster shots.

“In the Philippines, the uptake is maybe 75-80%. When we go to Africa, the uptake of early vaccination is probably more like 50% or even lower, chiefly because of logistic issues,” he said.

Tang, with North East Medical Services, said that while mainland China has nearly universal infant vaccinations now, previous vaccination rates there had varied by region.

“If you lived in a bigger city, you probably were receiving these birth dose vaccines,” Tang said. “But if you are in a more rural area, a lot of those public health interventions maybe weren’t as widespread until the early 2000s.”

She said she has seen higher vaccination rates abroad and in the United States lower the number of chronic hepatitis infections among her San Francisco patients.

“When I first came here in 2019, it was closer to maybe 60 women per year who were identified with hep B, and now it’s closer to 10,” she said. “So, it’s just been a very rapid decline.”

Treating one virus not like the other

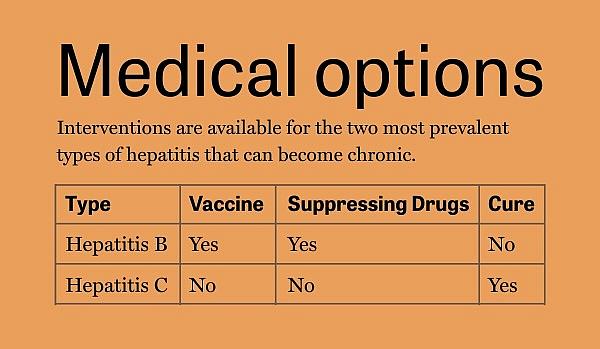

There is no cure for chronic hepatitis B, but a cure for chronic hepatitis C has been available since 2014. Patients take one of several antiviral drugs for 8 to 12 weeks. That protocol has a 95% cure rate. Bonacini said that drug came from federally funded research.

Future breakthroughs in fighting infectious disease are at risk, following the Trump administration’s decision to slash research and programs that monitor transmission of hepatitis, HIV and other viruses.

The B-United trial is unlikely to be affected by federal cuts, because it is at the stage where the funding in the United States is coming from the pharmaceutical company GSK. But if the trials are successful, U.S. government approval and rollout of the cure could be delayed.

Government research plus pharma investment

A clinical trial to treat an infectious disease comes at the end of a long road of scientific discoveries, public and private investment and luck. Basic research, usually funded by government grants, uncovers how an infectious disease works. Individual labs, often at universities, discover potential treatments and refine the drugs with government and private funding. Pharmaceutical companies then partner with scientists and file for a patent, which is valid for 20 years. The companies, and sometimes government, then fund more research including pre-clinical trials in animals and finally in humans.

Phase 1 trials test a drug for toxicity. Phase 2 trials test combinations of dosage and timing, while Phase 3 trials are large-scale efforts to determine if a drug is statistically helpful and to identify side effects and their prevalence. The B-United trial is in Phase 3.

If the drug works, the pharmaceutical company gets a 20-year patent. When such a patent expires, other companies are allowed to produce the drug in generic forms. The process has potential for high reward but also carries high risk: Most treatments fail, losing the company money.

The human equation

Experts already know it’s likely that the cure in clinical trials now will have different rates of effectiveness and possibly distinct side effects for different demographics, which poses a challenge because Asian Americans are so overrepresented among hepatitis B patients.

Researchers already expect different cure rates for different groups in the GSK trial.

“Asians will have lesser percentage of cures than non-Asian patients, probably because they had the disease longer, typically from birth. And there may be a difference in the immune system response,” Bonacini said.

Recruiting for clinical trials has proven to be easiest among more highly educated, middle-class patients. Bonacini’s efforts to recruit Asian American and Pacific Islander participants of various income levels have seen limited success.

However, Bonacini says he remains hopeful that offering a possible functional cure will attract more people.

“My expectation is that when people with hep B will realize that a cure is possible, they will be greatly interested in clinical trials that will have better and better outcomes,” he said.

The B-United trial isn’t the only effort to search for a cure for hepatitis B.

Wendy Lo, a San Francisco-based patient advocate for people with hepatitis B, expressed excitement in an email about the dozen novel therapeutics in early phases of trials, including ones developed using gene editing technology.

“All this makes the current Hepatitis B cure landscape an exciting, hopeful, and relevant space to watch!” she wrote.