Stigma, Insufficient Screening Keep Hepatitis B in the Shadows

This story was originally published in the San Francisco Public Press with support from our 2025 California Health Equity Fellowship.

Wendy Lo talks with a visitor to a dragon boat regatta at Lake Merced about hepatitis B and the services offered by the organization she works with, Hep B Free.

Jason Winshell/San Francisco Public Press

For Wendy Lo, who for three years has been an advocate for those with chronic hepatitis B, breaking the silence around her own diagnosis has been a slow, emotionally complex journey.

“I did it with a lot of hesitation and mixed emotions,” said Lo, recalling the first time she shared her experience in public.

Commonly known as a “silent killer” because it can have few symptoms, chronic hepatitis B can lead to liver damage or cancer, is not well studied and as a research area remains underfunded. Many living with it face significant social stigma, which discourages getting tested and leaves patients isolated and unwilling to open up about their experiences.

The silence hits immigrant communities the hardest, a phenomenon advocates have spent decades trying to fix. Asian Americans are disproportionately affected by hepatitis B, especially by chronic infections. Years of community work have led to better outreach, and new efforts like universal screening are starting to build momentum.

Persistent stigma

Lo lived quietly with the condition for 28 years. She discovered she had it at age 21 — just as she was preparing to study abroad. When she went to receive a required hepatitis B vaccination, instead of getting the shot, she learned she had been infected at birth.

Coming from the Chinese American immigrant community in San Francisco, Lo mostly heard about hepatitis B when relatives or neighbors died from it. She also saw how fear and myths about how it spreads led to exclusion in her social circle. She saw people being made to eat separately from others, even at shared family-style meals.

Unlike some other common liver diseases, hepatitis B is infectious. In Lo’s immigrant community, people were familiar with it because it was so prevalent among the group. But misunderstandings about how it spreads, like believing it could be passed through casual physical contact or shared meals, also fueled fear and stigma. Infections most commonly occur during childbirth, but the virus can also be transmitted through sexual contact or contact with blood and other bodily fluids. A highly effective vaccine is available, but vaccination rates vary from country to country.

That stigma made it even harder for Lo to speak up, as she felt the weight of representing not just herself, but also her family and community.

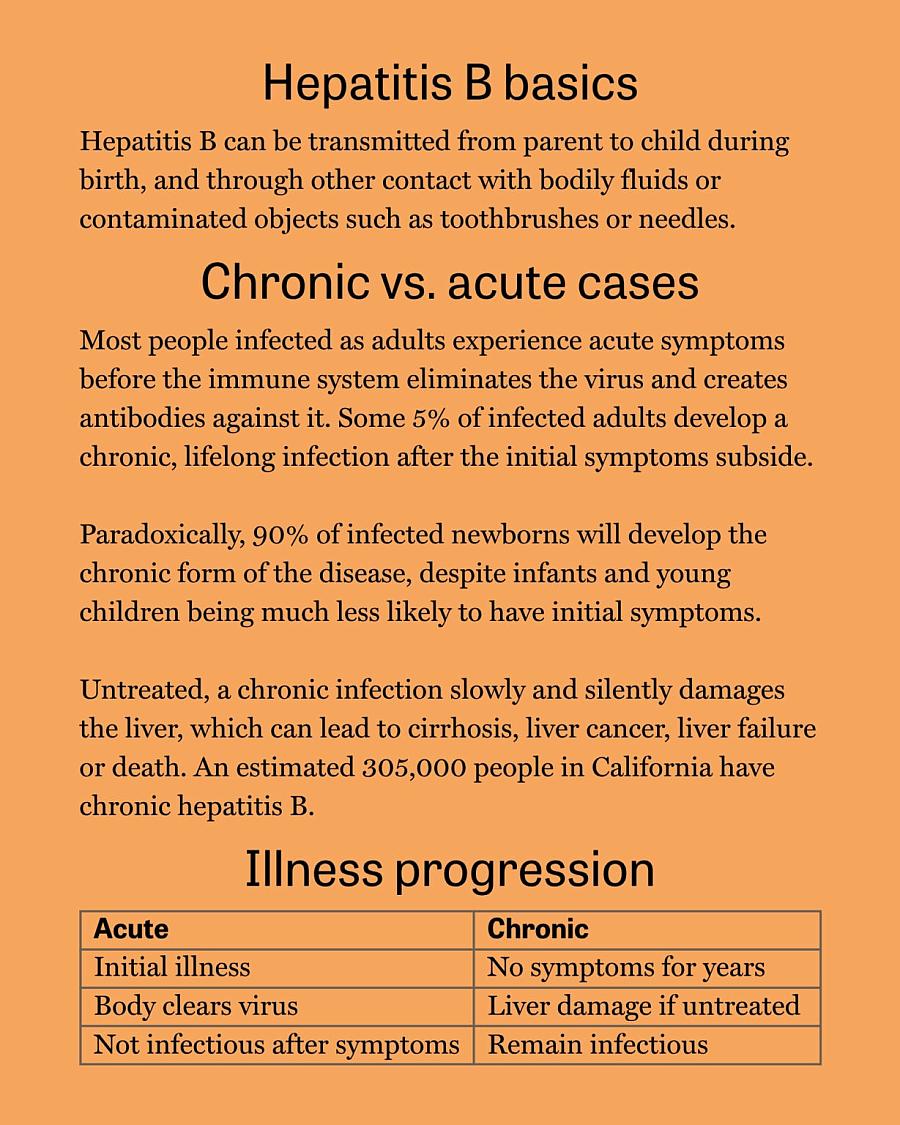

Sources: CDC, Mayo Clinic, and Heptology, Medicine and Policy

“What I do can reflect positively or negatively on my social circle,” she said. “Everyone’s staying silent in their little cubicle, thinking and suffering alone, but we’re also not helping one another.”

Hepatitis B patients describe the stigma showing up in many aspects of their lives: One remembered seeing billboards showing eyes yellow with jaundice meant to scare people into getting vaccinated. Another recalled hesitation from a life insurance agent to issue coverage, and one pediatrician’s misinformed warning that a parent with the disease should never kiss their child.

These kinds of misconceptions — intentional or not — often deepen fear and discourages testing. “People don’t want to even find out about it,” said Francis Yao, medical director of the Liver Transplant program at the University of California, San Francisco.

Universal screening could be a solution

Yao often receives referrals for patients with chronic hepatitis B, most commonly pregnant women who discover their infection because they are required to get screened during pregnancy. While there is not yet a cure for the infection, he said treatment can keep the virus under control and lower the chances of needing a liver transplant. But when the disease goes undetected and progresses to liver cancer, a transplant may be the only option. In other words, early screening is critical.

But for many patients, fear stands in the way. One solution experts suggest to reduce patients’ hesitation to screen for hepatitis B is to make it a routine part of primary care, so it feels like a standard health check rather than something tied to risk or judgment.

Until 2023, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommended hepatitis B screening only for individuals with known risk factors like being born in areas with a high prevalence of hepatitis B and injection drug use. This approach not only relied heavily on a doctor’s knowledge of the illness, but also placed an emotional burden on patients — many of whom worried about the implications of being identified as “at risk.”

“For me as a woman, a Chinese woman, one of the unspoken stigmas would be like: ‘Oh, how did you catch this,’ right? ‘Are you being promiscuous?’” Lo said. While hepatitis B can be transmitted sexually, most people who have it who were born in areas where the virus is endemic were infected during childbirth.

When the CDC updated its guidelines in 2023, it joined the first national push for universal hepatitis B screening. But how well the recommendation is being implemented remains unclear. With so many illnesses competing for their attention, not all physicians are aware of the new recommendations. A 2021 California law requiring health care providers to offer hepatitis B and C testing still recommended a risk-based approach, not a universal one.

Still, there are promising signs. Since the law passed, major health care providers in the Bay Area, and not just those serving predominantly Asian American populations, have begun adopting universal screening. Stanford Health Care, for example, implemented universal hepatitis B screening across 75 of its clinics and added alerts to its electronic health record system prompting physicians to offer the screening to every patient. A six-month survey of the change showed encouraging results: The electronic prompts were easy to use and led to more screening orders from primary care providers.

Getting to the community

One type of institution has long-established universal hepatitis B screening: community-based hospitals in San Francisco. Though the city lacks strong public health surveillance for chronic hepatitis B, it remains home to community-based hospitals like Chinese Hospital and North East Medical Services, which provide screening as a matter of course, as well as culturally sensitive service and outreach. That’s thanks to a history of local leadership by advocates for hepatitis B awareness.

In the early 2000s, a wave of unexpected deaths at early ages from hepatitis B shocked the Asian American community. In response, in 2017 local community leaders and physicians formed San Francisco Hep B Free, which recently changed its name to Hep B Free. The coalition brought together government officials and representatives from all major hospitals and health care providers in the region to meet regularly to discuss the illness. Together, they laid the groundwork for public outreach campaigns, free screenings and better education for doctors — many of whom had little experience with screening for and treating the disease.

Stuart Fong, who worked at Chinese Hospital at the time, was one of the founding members of the coalition. He helped launch a hepatitis B program at Chinese Hospital that offered free community screenings. Fong said staff would set up tables at community events to reach more residents. The goal was not just to vaccinate children, as most prevention efforts focused on, but also to reach their parents.

The coalition gained national attention with a provocative 2008 ad campaign showing 10 pageant queens and, to underline the statistic that 1 in 10 Asian Americans had hepatitis B at that time, asked in the caption: “Which one deserves to die?” The campaign was effective enough to inspire similar efforts in 10 other cities.

But the coalition’s momentum eventually slowed. According to Fong, major funding from pharmaceutical companies, which had once poured in while treatments were being developed and potential cures explored, eventually dried up.

Richard So, the new leader of the coalition, is working to revive those efforts. Hep B Free was a key player in advocating for California’s screening law, and is once again working to reconnect with hospitals and health care systems to educate providers on implementing successful screening models.

So is also reaching out to hepatitis B-focused organizations in other cities that were originally inspired by the coalition’s work, hoping to build a network that can share knowledge and expand efforts beyond San Francisco.

The goal is to “use the same formula — engaging the best stakeholders and partners — to expand hepatitis B advocacy in different places,” So said.

Dr. Jennifer Chen, also at Chinese Hospital, said successful efforts to expand detection go beyond simple policies, because even when doctors recommend that family members get screened, some people still opt out.

“It’s not just offering it. It’s making sure they understand why we’re doing it,” Chen said. That means physicians need to know how to communicate clearly and with cultural sensitivity. As a bilingual practitioner who can talk to her patients in Cantonese, she has noticed that the way patients describe the disease matters a lot during diagnosis.

“At least here, some things are spoken of very colloquially,” Chen said.

Many Chinese-speaking patients, for example, don’t say they have hepatitis B — they say they are “virus carriers,” a more familiar term in their community to describe this chronic infection. But if that phrase is translated directly without context, it can confuse doctors and lead to misunderstandings.

“Being able to communicate, I think that makes a huge difference,” Chen said.

So, from Hep B Free, wants to build on successful models through what he called a “blueprint project.” He and his collaborators are developing a handbook detailing how health care providers of various sizes deliver universal screening, so others can replicate it.

“We don’t have to reinvent the wheel. We can just pick from the list of ingredients and adapt it to our system to make it work,” he said.