Keep these five lessons in mind when reporting on undocumented children

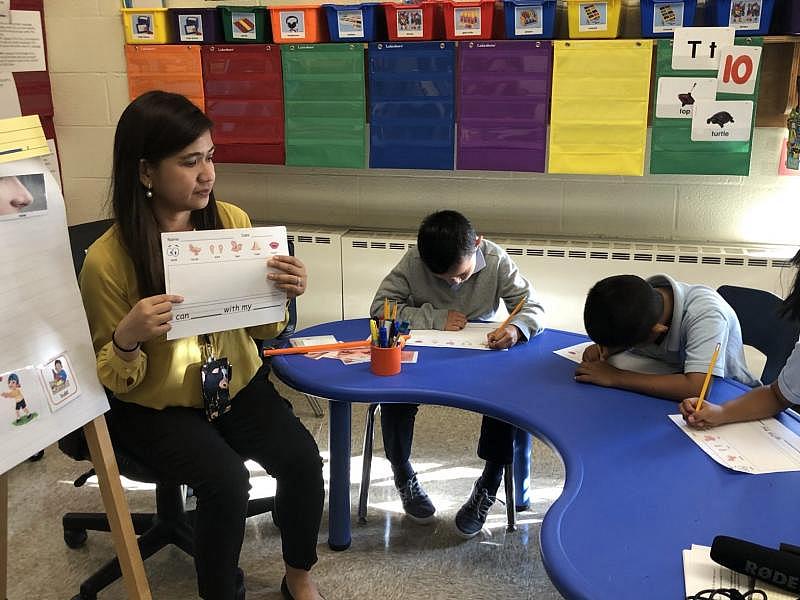

Tanya Gan Lim teaches a “newcomer class” in Maryland’s Prince George’s County school district.

(Photo: Kavitha Cardoza for The Hechinger Report)

Hundreds of thousands of children have entered the U.S., mostly from Central America, in the past few years. In 2019, undocumented children crossing the border dominated the headlines. Between October 2018 and September 2019, more than 75,000 unaccompanied minors — children who arrived in the U.S. without a parent or guardian — and almost 475,000 families with children crossed the southern border.

Much of the attention has focused on the poor conditions and children’s traumatic experiences in detention centers, including being separated from their parents. But even after they are released to family members or sponsors, their challenges continue. It can take as long as five years for asylum cases wind through the backlogged legal system. There was almost nothing in the popular media that focuses on these children’s lives during that time.

Most undocumented children enroll in U.S. public schools. There are no clear numbers available because by federal law, districts cannot ask for that information. But when looking at where these children were settling after they were released from detention centers, I realized that a school system close to me in Prince George’s County received the fourth-highest number of these children in the country.

As a longtime education reporter, I wondered how school systems were coping with the large influx of these children. Margarita Alegria, the chief of the disparities research unit at Massachusetts General Hospital and a professor at Harvard, explained the “compounded loss” these children experienced when they fled their homes. “They lost their familiar language, their customs, their habits, they lost their social networks. And many of them have lost their social status,” she said. Alegria said the trauma needs to be addressed before any learning can take place and she was convinced that teachers have a critical role to play. “Schools are where kids spend most of their time. It's really the system of care where we can make the biggest gains,” she said. While many educators I spoke to wanted to help, it was challenging to be thrust into the role of a first responder, helping children make sense of the upheaval, even as they struggled to find money and resources to help them.

This was a story that combined my interests — children, poverty, education and mental health. I spent most of 2019 finding sources who could introduce me to these children so they could tell their stories themselves. But the biggest challenge happened after I thought I was almost done reporting and writing in February 2020. COVID-19 hit and suddenly that’s all anyone was talking about. By the time there seemed to be the bandwidth to maybe think about something else later in the year, election coverage took over. I despaired over ever being able to share what I had gathered, even though I knew these children were more vulnerable than ever.

Here are some things I found helpful through my year of reporting:

1. Find a guide, or several: It took me a long time and, in some cases, repeated visits to build trust with families. I don’t speak Spanish and in many cases the children were distrustful of outsiders because of all they had been through. It did help tremendously that I was an immigrant and the children invariably were curious about where I was from and how I came to the U.S. I found guides who were educators who the children already trusted and could vouch for me. I sent them previous stories I had done so they were more familiar with my work, and at every interview I encouraged them to ask me questions about anything. We set ground rules early on: I would only use the child’s middle names and sometimes I didn’t identify which school they were in. These guides were tremendously helpful when I started to do follow up interviews towards the end of 2020 to update the series, as many children weren’t attending online school.

I also found a brilliant researcher, Sarah Pierce from the Migration Policy Institute, who was willing to spend hours explaining data and the legal issues surrounding these children, like “Are they considered ‘undocumented’ if they have applied for asylum?” and “Are these children legally allowed to work?” It also helped tremendously that my editor, Sarah Garland at The Hechinger Report, had written a book about undocumented children and was familiar with the issues I sometimes struggled with.

2. Understand the big picture: I spent a lot of time reading academic papers and speaking to experts on the challenges undocumented children face, before I started reporting. I needed to understand the issues involved because I knew it would be difficult for children to bring up issues on their own but if I seemed to know about it, they would answer. For example, I read that “family reunification” is often not the fairytale ending parents and children expect. After the initial excitement of being with each other, children miss their friends, the family that raised them and familiar surroundings. Sometimes they come to the U.S. and realize their parent has remarried and they have a new family to adjust to. And their parent typically works long hours. Many ask, “why did you bring me here?” Parents feel their children don’t recognize the sacrifices they’ve made to save up and bring them here. They have memories of the toddler they left, not the teenager that shows up. None of the children volunteered that the reunification was challenging, but when I asked about it, they talked freely about the difficulties.

3. COVID-19: The pandemic made everything more challenging, including tracking down parents and families and follow up interviews. Schools were closed so there was no easy and quiet place to meet safely. Educators and nonprofits who were helpful before the pandemic were swamped with helping families manage basic needs like food and health, and interviews were low on everyone’s priority list. I needed to be patient and as organized as possible so that when they had the bandwidth, I was ready to go.

4. Partner with multiple outlets: I wanted the story to have broad reach. When one of my first media partners fell through, I reached out to other outlets. Having multiple partners allowed me to use my reporting material in different ways. The Hechinger Report piece was for a national audience, the WAMU series was for a local audience. In the radio series I used at least one student voice in every piece so people could hear for themselves how young these kids were and the different challenges they faced. El Tiempo is running a Spanish version of the story online and in print, and some educators have said they will use the pieces to talk about trauma in class.

5. Accept there will be tears: Almost all the children I interviewed and almost all the educators cried at some point. I was not surprised — these were deep emotions that many hadn’t shared before. I gave them time and space to feel whatever they felt. Crying can be cathartic. But I also made time to have them talk about fun and happy things. Children giggled as they explained silly games they used to play in their home countries, how delicious their grandmother’s cooking was, and how proud they felt when they went home and taught their mother English words they had learned in school. I encouraged educators to talk about their little victories — the coats they collected for children who were experiencing winter for the first time, the ‘Thank you’ text messages they received, the student who struggled but graduated high school.

And not all the tears were from those I interviewed. I remember crying on my drive back home when I interviewed an 11-year-old and they asked me whether I had any work for them, like cleaning or gardening, so they could earn money to support their families. Or when a school counselor told me about a second grader whose mother covered her eyes when crossing into the U.S. because some people were drowning in the river. Or when a 7-year-old told me she wanted to learn English so she could be “smart.”

Read Kavitha Cardoza's fellowship stories here.