Outreach workers struggle to halt rising numbers of uninsured children

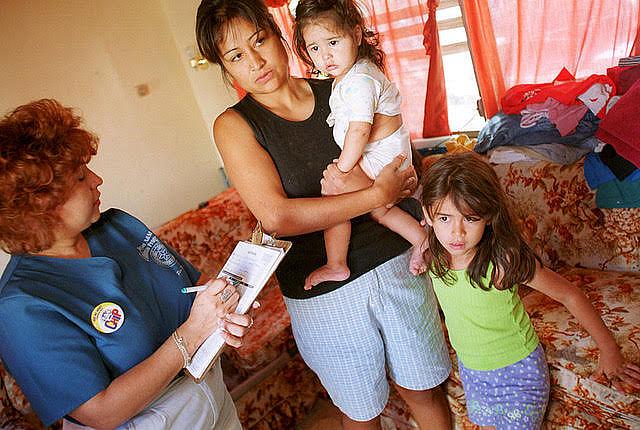

Marivi Wright, who helps with insurance enrollment at a children’s hospital in Jacksonville, Florida, often tries to assure immigrant parents that their residency status won’t be affected if they sign up their U.S.-born kids for public health insurance.

“But people talk on the street, and you’re not sure what’s going on and you’re afraid,” said Wright, a community outreach coordinator for the Players Center for Child Health at Wolfson Children’s Hospital. “You’d rather not enroll the child in Medicaid or any public benefits because you’re scared. … We try to explain to families the best we can. We try to put ourselves in their shoes.”

She said she often refers such parents to a legal aid organization for reassurance.

Wright’s experience reflects the challenges health insurance enrollment specialists face at a time when the uninsured rate for kids has been increasing. Health policy experts cite the chilling effect of the Trump’s administration’s actions on immigration as a major factor. The administration’s recent change to the “public charge” rule, reinstated in January by the U.S. Supreme Court, would allow the government to deny green cards to legal immigrants deemed likely to use public assistance.

But there are other basic obstacles these outreach workers have to deal with: families who lack internet access and transportation, don’t speak English as their first language, and might not know help is available.

That means enrollment specialists seeking to stem the growing number of uninsured kids are facing an uphill battle.

“You have to develop a thick skin,” said Wright’s colleague Tamico Spears. “I have some families trying to get Medicaid for over a year.” Her advice to other outreach workers: “Just don’t give up. At the end of that case number is an actual family in need of those services.”

The problem is especially acute in Florida, where the uninsured rate for children grew from 6.6% in 2016 to 7.6% in 2018, according to the Georgetown University Center for Children and Families.

Wright said she commonly sees families denied coverage because they lack the proper documentation. “Maybe they sent an old visa when maybe they have permanent legal resident status,” she said. “Maybe they didn’t send their card and sent the visa.”

One incorrect answer on an application can also get a kid turned down for insurance, she added.

A bigger issue enrollment workers face, however, is locating uninsured children in the first place.

“One thing we’ve kind of learned is there isn’t one magic strategy to find all the families and connect them with enrollment,” said Sarah Leethem, the Healthy Kids program director at the nonprofit Utah Health Policy Project. Her state’s rate of uninsured children rose from 6% in 2016 to 7.6% two years later, the Georgetown center found.

So her organization partners with other groups that work with low-income families, such as after-school programs, mobile health clinics and nonprofits that connect children with food.

Even after identifying the families, challenges remain.

“When you’re thinking about the populations that are eligible to enroll, sometimes that means people living in low-income, unstable housing, without reliable transportation, without reliable internet or phone access,” Leetham said. “For a lot of our population, English is their second, third or fourth language. There are a lot of refugees here, people who don’t have technology literacy.”

“Then you think about all the families that aren’t connected with us and just get frustrated with the process and quit,” she added.

Even as the federal government has cut funding for navigators who help people enroll in marketplace insurance through the Affordable Care Act, it has been awarding grants — including $48 million last year — to organizations that sign up kids for coverage through Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program.

Schools in general are a great way to connect with families, enrollment organizations say.

“The thing that I hear, across the board, is that partnerships with school districts are the most effective relationship when it comes to outreach,” said Karey Maciha, health center enrollment and outreach coordinator for the Arizona Alliance for Community Health Centers.

However, some schools and libraries restrict the kind of insurance outreach that can take place on their premises, she said.

Maciha said her organization has made a point of “narrowing down where you do your outreach rather than going out and trying to hit every single event in the community.” The group has also been targeting parent-teacher organizations and online moms’ groups and blogs.

Arizona also has a large number of Hispanic residents, so it’s important to have bilingual insurance navigators, Maciha said. Face-to-face enrollment outreach also seems to work better with that population, she said. Her organization is also working on culturally attuned messages to reach Native Americans.

Mercy Care, a federally qualified health center in Atlanta, does enrollment outreach at local public schools, a youth shelter and public housing complexes. An enrollment worker even has an office at one of the complexes, and the group is looking to expand his hours to the evenings and weekends to reach more people.

“It’s just really linking up with folks where they are and getting in front of them and getting them educated,” said Anitra Walker, vice president of operations for Mercy Care.

Georgia’s uninsured children rate for children climbed from 6.7% to 8.1% over the recent two-year period.

Ashley Mckenzie, an outreach and enrollment specialist for Mercy Care, said she tries to target parents for Medicaid enrollment because if they qualify, their kids often do too.

Wright, the outreach professional in Jacksonville, described what’s at stake: “If a child doesn’t have a relationship with a family doctor, the child is going to miss school, the parent is going to miss work, the grades are going to be lower, the kid is going to show up at the ER.”

“Unhealthy kids turn into unhealthy adults,” added her coworker Spears, from the Florida children’s hospital. “We need to talk to our politicians that these problems are not going away. And (these kids) are going to become voters.”