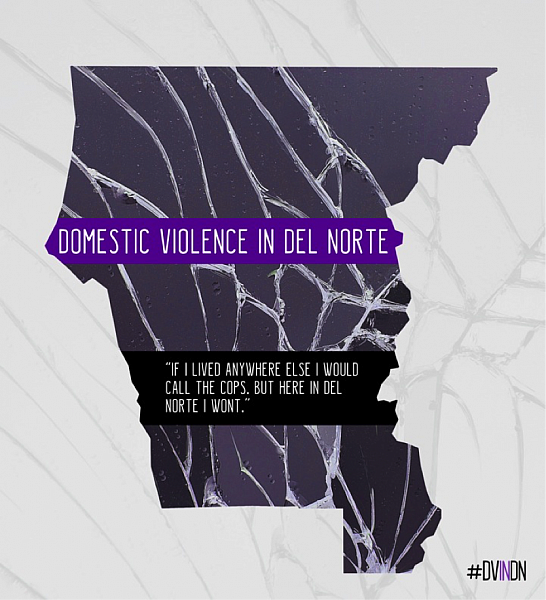

Reporting from the front lines of domestic violence in California’s far north

Tara Williams, a victim of domestic violence, shown in a family photo fishing at the mouth of the Klamath River. (Image via JPR)

It’s around 10 p.m. when I call a crisis worker for victims of domestic violence in remote Northern California.

I’m panicking, 150 miles away in Oregon.

I’m really afraid someone is going to get hurt tonight.

Vicky takes in what I’m saying calmly. She agrees to drive by an address near her neighborhood.

It’s an address that shows up over and over in the Del Norte County 9-1-1 call logs. I came across it looking into how local law enforcement responds to reports of domestic violence in a county with the highest rate of such reports in California. My findings make up one story in a series originally intended for a local audience, namely readers of the Del Norte Triplicate newspaper and website. In the middle of this project I moved to Southern Oregon to become a public radio producer. The reporting continued in both print and radio through collaboration with a still-local Triplicate reporter. He collected police and court records, while I taped interviews on weekend trips and over the phone.

Each story in the series focuses a different lens on what happens after people in Del Norte County report domestic violence.

The night I call Vicky the crisis worker, I had just hung up with a woman who reported her husband to the Sheriff’s Office twice in the month prior. He was not arrested by responding deputies either time, even though he had just been convicted for an assault on her that took place six months earlier. A different woman called about him four years before that. I saw the choke marks on her neck in a picture taken by police. He wasn’t arrested then, either.

I decide to name him in a story.

I want to warn his current wife before it comes out. It honestly doesn’t occur to me to try and contact him. Instead, I message her on Facebook, say I’m a reporter writing a story I think she should know about. I leave my phone number and ask that she call me when alone.

Hindsight comes within the hour.

She calls me. My heart’s pounding as I spit out the facts, without verifying that she is in fact alone.

I tell her I’m writing about domestic violence, that I researched the police response to the 9-1-1 calls she recently made, that I don’t think those calls were handled well and there’s going to be a story in the local paper soon. She isn’t named, but her husband is.

She echoes the last words and a male voice swells in the background.

“What’s that [expletive] saying about me?”

The woman on the phone becomes desperately polite.

“I’m so sorry ma’am, could you please hold on a minute?”

I hear him screaming; her begging him to be quiet.

She comes back on the line: “Ma’am, I’m so sorry about that. What were you saying?”

I tell her I think it’s a bad idea to continue our conversation, but that she can call me anytime when he’s not there.

After we hang up, I burst into tears. Then I call Vicky.

I had already interviewed Vicky about her job working with victims in crisis and her personal experiences surviving domestic violence. She lives near the woman I’d just contacted.

Vicky calls back to tell me she didn’t see or hear anything unusual at the woman’s address.

I think about how little noise strangulation actually makes.

Vicky sighs. I can hear the judgment in her voice. She asks me: “Why would you write something that could hurt someone?”

The next day, the woman calls back. She says she’s okay. This time she assures me she’s alone. She apologizes for her husband’s behavior the night before. I apologize for mine.

Then I paraphrase the facts at my disposal. I ask if they’re accurate.

“Yeah,” she says, “And it took the cops forever to get here the second time.”

In this case, forever is about an hour.

Before we hang up, I give her Vicky’s phone number. It’s all I can think to do.

Within a month, there’s another 9-1-1 call to her address, another assault on her.

I reached other domestic violence victims through Facebook in a much less traumatic and reckless way. I posted a Google Forms survey to local pages — the community forums, swap meets and neighborhood watch groups.

This survey asked people A) how domestic violence had affected them, and B) if they called the police to report it.

People started sharing it, and I soon got 44 responses. Many were detailed. Fifteen respondents left follow-up contact information. I taped interviews with three of those women.

I learned of another victim through her obituary.

It said she died in a tragic motor vehicle accident.

In the weeks and months following her death at 26, I interviewed family and friends about how domestic violence affected her life. They all supported court and police records to suggest her partner had a history of abusing her, though he’s never been convicted of any related crimes.

Conversations with her father were perhaps the most difficult.

We first meet at his house, where I just get out of the way and let him talk. He shares memories of his daughter, the things she did in childhood that moved him. He talks about taking her to the emergency shelter to get away from her fiance. He says he wanted to retaliate on her behalf, but that’s not who he is anymore. He says he always thought there’d be more time to fix his relationship with his daughter, then time ran out. Later on, I learn of allegations that he, too, abused his family in years past.

I draft the story without calling him to readdress this information.

Dread settles in. But when I finally reach out to him, it doesn’t go the angry way I expect.

I lay out the facts at my disposal. I ask him to own the past more honestly, and in so doing spare the story about his daughter any more brutal details from police and court records. In my opinion, he responds bravely. He says it goes deeper than her, deeper than him, and deeper than his parents. He speaks of a community where spousal abuse has become commonplace and says he wants to stop that hurting.

I rewrite the story.

In the aftermath of publication, people in the community vented on Facebook. Some posted messages of support, others of disgust on the father’s wall and those of other sources. There were threads full of regret and crying emojis. Others were appalled we would exploit a grieving family. One woman said she had very mixed feelings, that on the one hand it’s important to get these things in the open, but that she wouldn’t wouldn’t want something like that written about her.

In processing all this, I keep circling back to Vicky’s question the night I called her to do a welfare check on someone neither of us had ever met before:

“Why would you write something that could hurt someone?”

It’s a question every journalist needs to be able to answer. I hope anyone covering domestic violence will keep it close to heart as they decide how to protect victims, without perpetuating their silence.